National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

Travelers may find it difficult to empathize with locals, according to experts. Here, tourists in 2016 buy fruit juice at a market stall in Siem Reap, Cambodia.

Travel is said to increase cultural understanding. Does it?

While researchers say travel does affect the brain’s neural pathways, true empathy remains an elusive destination.

Empathy is commonly defined as “putting yourself in another person’s shoes” or “feeling the emotional states of others.” It’s a critical social tool that creates social bridges by promoting shared experiences and producing compassionate behavior. But can empathy be learned? And can travel help facilitate this learning? The answer is complicated. “Research has shown that empathy is not simply inborn, but can actually be taught,” writes psychotherapist F. Diane Barth in Psychology Today . While past research has indicated that empathy is an unteachable trait, newer research—including a 2017 Harvard study —suggests that the “neurobiologically based competency” of empathy is mutable and can be taught under the right circumstances. Whether seeing the world actually opens travelers’ minds—that it makes travelers more empathetic—is up for debate. In a 2018 Harris Poll of 1,300 business travelers, 87 percent said that business trips helped them to be more empathetic to others, reports Quartz . And in a 2010 study , Columbia Business School professor Adam Galinsky found that travel “increases awareness of underlying connections and associations” with other cultures. While self-defined empathy and awareness are unreliable measurements, it stands to reason that cross-cultural exposure through travel would at least create conditions for checking conscious and unconscious biases. “If we are to move in the direction of a more empathic society and a more compassionate world, it is clear that working to enhance our native capacities to empathize is critical to strengthening individual, community, national, and international bonds,” writes Helen Riess, associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and author of the 2017 report.

But the coronavirus pandemic and, more recently, the global Black Lives Matter protests have forced an uncomfortable reckoning—that all the travel in the world might not be enough to engender the deep cross-cultural awareness people need now.

“There’s this false adage that travel opens minds, but that’s not [a built-in] fact about what travel does,” says Travis Levius, a Black travel journalist and hospitality consultant based in London and Atlanta. “Travel does not automatically make you a better person,” nor does it clue you into “what’s going on in terms of race relations.”

Black Travel Alliance founder Martina Jones-Johnson agrees, noting that tourism boards have made it “overwhelmingly clear that travel doesn’t necessarily build empathy.”

The lack of diversity within the travel industry itself suggests that there’s much work to be done to make the industry as inclusive as the world of travel consumers. According to a 2019 annual report by the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, workers in the leisure and hospitality industry were overwhelmingly white. Consumers, meanwhile, say they want to spend their money on travel companies whose employees reflect the world they work in, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council .

Additionally, companies that embrace inclusivity may have a better chance of avoiding tone-deaf messages , such as using “free at last”—the line is from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Dream” speech—to caption a billboard depicting white children jumping into the Florida Keys. The advertisement, which has since been taken down, launched in the wake of the killing of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis that sparked worldwide protests against police brutality.

(Related: Learn why it’s important to have diverse perspectives in travel.)

Karfa Diallo leads a tour of sites related to the trans-Atlantic slave trade in Bordeaux, France, in June 2020. Participating in activities that amplify marginalized voices and experiences can go a long way toward developing empathy, say experts.

A road paved with good intentions

Interestingly, modern tourism has fairly empathic origins. In the 1850s, Thomas Cook used new railway systems to develop short-haul leisure travel as respites for hard-working British laborers, according to Freya Higgins-Desbiolles, a senior lecturer on tourism management at the University of South Australia.

A hundred years later the United Nations declared reasonable working hours, paid holidays, and “rest and leisure” as human rights . By the 1960s, spurred by related movements to increase holiday time, the leisure sector had coalesced into a full-fledged professional industry.

Since then, the World Tourism Organization and international aid groups have championed tourism as both “a vital force for world peace [that] can provide the moral and intellectual basis for international understanding and interdependence,” as well as an economic development strategy for poorer nations.

But not everyone agrees that the travel industry has lived up to these lofty goals. In recent decades, it has been accused of doing just the opposite. As Stephen Wearing wrote nearly 20 years ago : “tourism perpetuates inequality” because multinational corporations from capitalist countries hold all the economic and resource power over developing nations.

(Related: This is how national parks are fighting racism.)

These days, inequality is baked into the very process of traveling, says veteran Time magazine foreign correspondent and Roads & Kingdoms co-founder Nathan Thornburgh. “Your frequent flier status, the stupid little cordon separating the boarding lines, the way you take an Uber or cab from the airport after you land, not a bus or colectivo or matatu —those all reinforce divisions, not empathy,” he writes in an email. “And that’s just getting to a place.”

Empathy’s downsides

Experts say developing empathy isn’t easy and comes with a host of problems. Joseph M. Cheer, a professor at Wakayama University’s Center for Tourism Research in Japan, notes that empathy inherently “others” another person.

In his 2019 study of westerners on a bike tour in Cambodia, Cheer found that despite the prosocial aspects of the experience—visiting local non-governmental organizations, interacting with local Cambodians—post-tour interviews revealed that the tourists didn’t understand the cultural context of the outing. The visitors leaned into problematic tropes like “happy,” “lovely,” and “generous” when describing locals or simply saw Cambodians as service providers.

This “othering” bias, Cheer says, becomes more noticeable the greater the distance between tourists and locals, and especially so in strictly transactional encounters, such as in hotels.

A worker at a resort in Bali. Researchers say visitors should make a commitment to understand local cultures by moving past transactional interactions.

Our individual travel experiences oppose our best intentions, says travel writer Bani Amor, who has written extensively on race, place, and power.

“The stated [positive] intentions are completely contradictive to what happens in the tourism industry and how oppressive it is to BIPOC [Black, indigenous, and people of color] around the world, how tourism laborers are being treated, and how they’re being dispossessed, not having a right to their own land and to enjoy our own places,” says Amor, who has worked in the tourism industry in their ancestral home of Ecuador.

“You can only really know your own experience,” adds Anu Taranath, a racial equity professor at the University of Washington Seattle and a second-generation immigrant.

“I think we can develop empathetic feelings and sort of crack open our sense of self to include other people’s experiences in it. We can only deepen our own understanding of who we are in an unequal world and how that makes us feel and how that motivates us to shift our life in some way or another.”

I think in its purest form, empathy is basically impossible. I can weep for you, but I can’t weep as you. Nathan Thornburgh , founder, Roads & Kingdoms

Or as Thornburgh puts it: “I think in its purest form, empathy is basically impossible. I can weep for you, but I can’t weep as you.”

Traveling deeper

While experts conclude that travel may not inspire enough empathy to turn tourists into social justice activists, the alternative—not traveling at all—may actually be worse.

“[B]ecause travel produces encounters between strangers, it is likely to prompt empathetic-type imaginings, which simply wouldn’t be there without the proximity created by travel,” says Hazel Tucker in a 2016 study published in the Annals of Tourism. It’s also one reason why it’s important to expose children to travel at an early age.

Yet truly transformational experiences require more than just showing up with a suitcase. It requires energy, effort, and commitment on the part of tourists, as well as specific conditions, says Higgins-Desbiolles. “Visitors need to be prepped for the interaction so that they are ready to engage with the people on an equal level,” she notes.

Taranath’s book Beyond Guilt Trips: Mindful Travel in an Unequal World may provide some starting points. “It’s an invitation to think more carefully about our good intentions and where they really need to be challenged,” Taranath explains. “How do you think about identity and difference in an unequal world? What does it actually look like?”

Additionally, Tucker suggests embracing what she calls “unsettled empathy”: learning about the cultures you’re planning to visit and sitting with uncomfortable legacies of colonialism, slavery, genocide, and displacement from which no destinations are exempt.

Barbara Manigault, a Gullah sweet grass basket weaver, practices her craft in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. American tourists with limited travel opportunities can find many places in the U.S. to learn more about other cultures.

That background can be the basis for meaningful conversations, which Cheer found are “the key element that prompted empathy.” Thornburgh adds that travelers should seek out places where there is “an equal and humanistic exchange, or something approaching it, between the visitors and the visited.”

(Related: The E.U. has banned American travelers. So where can they go? )

Toward that end, experts generally ruled out cruises. Instead, immersive experiences like Black Heritage Tours that amplify historically marginalized voices provide better opportunities for meaningful connections.

Fortunately for would-be travelers, those opportunities can be found even in these pandemic times, when many countries are restricting international travel, especially for Americans.

“We are so lucky in this country that the whole world has come here to build their lives, in big cities and small, and that we have Black and [Native American] communities throughout,” says Thornburgh. “Go to their restaurants, lend your talents to their schools, help them raise money for their playgrounds.

“You want travel? You want to experience different cultures? Start at home. Start now.”

Related Topics

- CULTURAL TOURISM

- PEOPLE AND CULTURE

You May Also Like

How to make travel more accessible to the blind

The Masterclasses 2023: 10 travel writing tips from our experts

Fuel their curiosity with your gift.

Before the Great Migration, there was the Great Exodus. Here's what happened.

Americans have hated tipping almost as long as they’ve practiced it

Who were the original 49ers? The true story of the California Gold Rush

L.A.'s eclectic food trucks serve up everything from Nashville hot chicken to scallop ceviches

10 of the best hotels in Tokyo, from charming ryokans to Japanese onsen retreats

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Photography

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Destination Guide

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

What Can Affect the Intention to Revisit a Tourism Destination in the Post-pandemic Period? Evidence from Southeast Asia

- Conference paper

- First Online: 21 February 2024

- Cite this conference paper

- Duong Tien Ha My 3 &

- Le Thanh Tung 3

Part of the book series: Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics ((SPBE))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Modern Trends in Business Hospitality and Tourism

121 Accesses

As tourism plays an important role in the economic development of many countries, it is essential to understand the factors that drive tourists’ attitudes and intentions to revisit a destination. Therefore, this paper aims to explore the factors that may influence revisit attitudes and intentions in the post-pandemic period. To fulfil this research objective, we used an online survey to collect data as it was a suitable and effective tool in the research context. After data cleaning, there were 431 valid responses for analysis. Cronbach’s alpha, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) were used to assess the reliability, the discriminant validity, and the convergent validity of all constructs. After checking the validity and reliability of the scale, the structural equation modeling is employed to test the hypotheses on the relationships between variables. We find that past travel experiences, healthcare systems, and crisis management positively impact people’ revisit attitude, which in turn affects their revisit intentions. Given restricted resources, our findings suggest that governments and travel companies should consider resources carefully and properly invest in the essentials when implementing policies to encourage tourism attraction.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

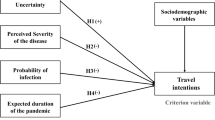

COVID-19 pandemic and tourism: The impact of health risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty on travel intentions

Tourists’ Behaviour in a Post-pandemic Context: The Consumption Variables—A Meta-Analysis

Tourists’ Travel Motivations During Crises: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abbasi, G. A., Kumaravelu, J., Goh, Y.-N., & Dara Singh, K. S. (2021). Understanding the intention to revisit a destination by expanding the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). Spanish Journal of Marketing – ESIC, 25 (2), 282–311.

Article Google Scholar

Ali, F., Ciftci, O., Nanu, L., Cobanoglu, C., & Ryu, K. (2021). Response rates in hospitality research: An overview of current practice and suggestions for future research. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 105–120.

Avraham, E. (2015). Destination image repair during crisis: Attracting tourism during the Arab spring uprisings. Tourism Management, 47 , 224–232.

Casali, G. L., Liu, Y., Presenza, A., & Moyle, C.-L. (2021). How does familiarity shape destination image and loyalty for visitors and residents? Journal of Vacation Marketing, 27 (2), 151–167.

Castañeda-García, J. A., Sabiote-Ortiz, C. M., Vena-Oya, J., & Epstein, D. M. (2022). Meeting public health objectives and supporting the resumption of tourist activity through COVID-19: A triangular perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 26 , 1617.

Google Scholar

Chon, K. (1989). Understanding recreational travelers’ motivation, attitude, and satisfaction. The Tourist Review, 44 (1), 3–7.

Chung, J. Y., Lee, C.-K., & Park, Y.-N. (2021). Trust in social non-pharmaceutical interventions and travel intention during a pandemic. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 27 (4), 437–448.

Donohoe, H., Pennington-Gray, L., & Omodior, O. (2015). Lyme disease: Current issues, implications, and recommendations for tourism management. Tourism Management, 46 , 408–418.

General Statistic Office of Vietnam. (2023). http://www.gso.gov.vn/ . Accessed on 19 Feb 2023

Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29 (1), 1–20.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31 (1), 2–24.

Hasan, M. K., Abdullah, S. K., Lew, T. Y., & Islam, M. F. (2019). The antecedents of tourist attitudes to revisit and revisit intentions for coastal tourism. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 13 (2), 218–234.

Huang, S., & Hsu, C. H. (2009). Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. Journal of Travel Research, 48 (1), 29–44.

Jalilvand, M. R., Samiei, N., Dini, B., & Yaghoubi, P. (2012). Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination and travel intention: An integrated approach. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 1 (1–2), 134–143.

LaTour, S. A., & Peat, N. C. (1979). In W. L. Wilkie (Ed.), Conceptual and methodological issues in consumer satisfaction research, Ralph day, Bloomington (pp. 31–35). Indiana University Press.

Moreno-González, A. A., León, C. J., & Fernández-Hernández, C. (2020). Health destination image: The influence of public health management and well-being conditions. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16 , 100430.

My, D. T. H., & Tung, L. T. (2023). Travel intention and travel behaviour in the post-pandemic era: Evidence from Vietnam. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 14 (1), 171–193.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17 , 46–49.

Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Seyfi, S., Rastegar, R., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Destination image during the COVID-19 pandemic and future travel behavior: The moderating role of past experience. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 21 , 100620.

Reisinger, Y., & Mavondo, F. (2005). Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of travel risk perception. Journal of Travel Research, 43 (3), 212–225.

Santana, G. (2004). Crisis management and tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 15 (4), 299–321.

Su, L., Pan, L., & Huang, Y. (2023). How does destination crisis event type impact tourist emotion and forgiveness? The moderating role of destination crisis history. Tourism Management, 94 , 104636.

Tsai, S. P. (2012). Place attachment and tourism marketing: Investigating international tourists in Singapore. International Journal of Tourism Research, 14 (2), 139–152.

Tung, L. T. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global tourism: A synthetic analysis. African Journal of Hospitality Tourism and Leisure, 10 (2), 727–741.

Uğur, N. G., & Akbıyık, A. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 on global tourism industry: A cross-regional comparison. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36 , 100744.

Wang, L.-H., Yeh, S.-S., Chen, K.-Y., & Huan, T.-C. (2022). Tourists’ travel intention: Revisiting the TPB model with age and perceived risk as moderator and attitude as mediator. Tourism Review, 77 (3), 877–896.

WHO. (2020). Strengthening the health system response to COVID-19 . https://www.who.int/europe/tools-and-toolkits/strengthening-the-health-system-response-to-covid-19

World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). (2022). Travel & Tourism – economic impact 2021 . United Kingdom.

Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management, 26 , 45–56.

Zheng, D., Luo, Q., & Ritchie, B. W. (2021). Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tourism Management, 83 , 104261.

Download references

Acknowledgments

This research received no funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Economics and Public Management, Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Duong Tien Ha My & Le Thanh Tung

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Le Thanh Tung .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Business, Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Adina Letiția Negrușa

Monica Maria Coroş

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

My, D.T.H., Tung, L.T. (2024). What Can Affect the Intention to Revisit a Tourism Destination in the Post-pandemic Period? Evidence from Southeast Asia. In: Negrușa, A.L., Coroş, M.M. (eds) Sustainable Approaches and Business Challenges in Times of Crisis. ICMTBHT 2022. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-48288-5_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-48288-5_7

Published : 21 February 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-48287-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-48288-5

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Psychology of Travel

New ways of thinking about global mobility and movement.

Andrew Stevenson Ph.D. on September 5, 2023

Fear and worry are common responses to travel and tourism, but sometimes they can help us plan our journeys and stay safe.

Andrew Stevenson Ph.D. on August 3, 2023

Do you find it hard to relax and focus on the present moment when traveling? Understanding the link between time perception and vacation preferences can help you let go.

Social Life

Andrew Stevenson Ph.D. on July 26, 2023

Do you prefer to travel alone or in groups? Well, you may have little choice. Traveling without being influenced by others is virtually impossible, social psychologists find.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Tourists’ Perceptions of Destination Travel Attributes: An Application to International Tourists to Kuala Lumpur

2014, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

Related Papers

Özlem Güzel

Because films create destination images with the scenes and the actors they use, films can provide rich knowledge of the attributes of a destination such as cultural structure, historical places, event facilities, and shopping activities. These destination attributes (DAs) not only play an important role in the tourist decision process of where to travel, but also have an effect on tourist satisfaction about the visit. With this context in mind, this study aims to (1) explore the construction of DAs, (2) analyze the differences between film-induced tourists (FITs) and non-film-induced tourists (NonFITs), and (3) determine the relationship between DAs and tourist satisfaction. This study focuses on Arabian tourists (n=270) in Turkey because the production of many films has been transferred lately from Turkey to Arabian countries. The study analyzes 23 DAs into seven dimensions: halality, locality, shopping facility, culture and climate, activities, physical environment, and natural beauty. Multiple regression analysis is applied to examine the relative impact of DAs on Arabian tourist satisfaction with Turkey. The results reveal a significant difference between FITs and NonFITs with regard to perception of DAs (shopping facilities, culture and climate, and activities). Regression analysis results show that there is a relation between the locality and activities of DAs and tourist satisfaction for FITs, whereas there is only a physical environment relation to satisfaction for NonFITs.

Norzalita Aziz

The marketing of heritage coincides with the emergence of marketing as an academic discipline in the 1950s. This research seeks to determine domestic and international tourists' expectations and perceptions of the heritage site of Melaka in Malaysia by measuring their satisfaction level using eight travel attributes.

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

Saeed Pahlevan Sharif

Tourism Management

Rachana Phem

shahrul nizam

The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between tourism service quality with overall satisfaction, intention to revisit and willingness to recommend to relatives and friends. This study is significant in at least two ways. First, it extends the work of Rimmington and Yuksel (1998) who included transport as a general component. This study includes taxis as a separate component since taxis are a popular transportation mode. Second, it provides information to multiple government agencies on ways to improve satisfaction among tourists. data is collected from foreign tourists who visited Kuala Lumpur. A total of 199 completed questionnaires were received. There are three notable findings; first, there is a significant relationship between accommodation service quality, hospitality, entertainment, transportation, taxi service quality and overall satisfaction. Second, there is a significant relationship between overall satisfaction and intention to revisit Kuala Lumpur. Third, there is a significant relationship between overall satisfaction and willingness to recommend Kuala Lumpur to friends and relatives.

International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Systems

Publishing India Group

This study attempts to investigate the foreign tourists' satisfaction within Indian tourism context, specifically with reference to the destination-based attributes. The study was conducted in Golden Triangle (Delhi-Agra-Jaipur) in India with a sample of Chinese and Japanese tourists. Gathering data was analyzed using factor and regression analysis and t-tests. The research findings indicated that the main determinants of both Chinese and Japanese tourists' holiday satisfaction were that accommodation services, safety & security and destination/ sightseeing dimensions. Further, findings indicate statistically significant differences between Chinese and Japanese tourists' perceptions of destination-based attributes in India. The results are also important for all tourism stakeholders in order to increase tourists' satisfaction and develop the quality of tourism product in India especially in Golden Triangle (Delhi-Agra-Jaipur). The main suggestion of this study is that more similar studies should be undertaken from different perspectives to enhance competitiveness and sustainability of tourist destinations in the study area.

DR. ALAA ABUKHALIFEH

Service quality researchers to date have paid scant attention to the issue of the dimensions of service quality. Much of the earlier work accepted the content measured by the SERVQUAL instrument. Following the argument that SERVQUAL only reflects the service delivery process, the analysis results (reliability, confirmatory factor analysis and descriptive statistics) from hotel restaurant sample revealed that Parasuraman’s model is a more appropriate representation of service quality for this study. The survey conducted was distributed to 700 customers who dine in hotel restaurants’ within six cites Amman, Irbid, Madaba, Dead Sea, Petra and Aqaba in Jordan. Of these 700, 460 surveys were returned and 30 of these surveys had more than 25% of the items unanswered, resulting in an effective sample of 430 usable completed questionnaires. Five constructs, tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy were operationalized in order to test the research model. The current study seeks to extend our understanding of service quality by assessing a five‐dimensional model based on a first wave of researchers.

Masitah Muhibudin

Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM)

Tessa Eka Darmayanti

Bandung is famous in many tourism sectors, such as nature, fashion and culinary. Bandung well known by having the variousity of culinary. Based on current observations, many culinary tourism facilities – restaurant in Bandung has a typical interior layout that related to local culture. The characteristic arrangement of interior elements in the restaurant are using various design vernacular and vintage products in the same time, which give a unique phenomenon and reflecting local ethnicity. There is a perspective differences between the traditional society as the creator and user of the vernacular products, with the modern society. The differences is due to cultural factors, that traditional society has mythic culture background, while modern society has ontology culture background. This paper has descriptive interpretative approach, will be focusing on how modern society treats the vernacular design and vintage products in the present time and the arrangement of products in interior of modern-ethnic restaurant – Warung Lela. The summary of applying vernacular design and using vintage products as interior element to attract in tourism purposes is possible to change the meaning of the vernacular design as the supporting elements.

Bahman Shojaeivand ------- بهمن شجاعی وند

RELATED PAPERS

Somaskanthan Maruthaiah , rosmalina abdul rashid , Shazali Johari , Romzee Ibrahim , Tiara Ara

Zubair Hassan , nishan waheed

TOURISMOS: AN INTERNATIONAL MULTIDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL OF TOURISM

DR. ALAA ABUKHALIFEH , BADARUDDIN MOHAMED

Hotel Restaurants' Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty: A Test of Mediation

Muhammad Akmal Azman

Muhammad Akmal Azman , Syahmi Sebery

Syahmi Sebery , Muhammad Akmal Azman

James Kennell

Hamzah Jusoh , Habibah Ahmad , Amriah Buang

OURNAL OF GLOBAL MANAGEMENT JANUARY 2013. VOLUME 5. NUMBER 1

Ebrahim moradi

International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage

Gamal S . A . Khalifa

Nor Fatimah Abd Hamid , Nurul Najib

Hamzah Jusoh

Brian E M King

Journal of Management and Sustainability

iefpedia.com

Dziauddin Sharif

yohana tania

Khairul Nizar Ismail

Zainudin Awang

Celyrah B Castillo

Hossein Nezakati

Nik Maheran

Dr. Aminuddin Yusof

farah adibah

Putri Syaidatul Akma Mohd Adzmi

Erdogan Ekiz , Yusniza Kamarulzaman , Boey Sai

ECOTOURISM POTENTIALS IN MALAYSIA

Elizabeth Pesiu

Emira Raida

Aminuddin Yusof

International Journal on Social Science, Economics and Art

J . A. R . C . Sandaruwani

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The impact of perceptions of positive covid-19 information on travel motivation and intention: evidence from chinese university students.

- 1 School of Physical Education, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 2 Department of MA Filmmaking, University for the Creative Arts, Farnham, United Kingdom

- 3 State Information Center, Beijing, China

- 4 School of Tourism and Urban-rural Planning, Zhejiang Gongshang University, Hangzhou, China

The COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the tourism industry in various ways, including tourists’ travel motivations and intentions. Unlike previous studies that have focused on the dark side of the pandemic, this study adds the dimension of perceptions of positive information on COVID-19 to the Theory of Planned Behavior to explore their influence on travel motivation and intention. A total of 470 valid questionnaires were collected from a sample of Chinese university students. The results showed that the students’ perceptions of positive COVID-19 information positively impacted their travel intentions through the variables of perceived behavioral control, travel attitudes, and travel motivations. Perceived behavioral control was the mediating variable that most explained the impact of perceptions of positive COVID-19 information on travel motivation and intention. This study contributes to the understanding of the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism and of university students’ travel motivations and intentions. It also offers implications for the tourism industry to formulate relevant recovery strategies during and after the pandemic.

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has been deemed the most influential and destructive event of the 21st century, especially for the tourism industry ( WTTC, 2020 ). It led many countries and regions to impose travel restrictions, which has had a serious impact on the tourism industry ( Yang et al., 2020 ). As a result of the pandemic, 96% of European countries enforced travel bans, and the valuation of hotels, airlines, and cruise companies declined significantly ( Peter and Dritan, 2020 ; Sharma and Nicolau, 2020 ). According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization, one in three destinations worldwide were closed ( UNWTO, 2021b ), and the arrivals of international tourists was decreased by 72% from January 2020 to December 2020 ( UNWTO, 2021a ). Due to this, the export revenues have a loss of USD 935 billion ( Kumar et al., 2021 ). Meanwhile, the risk of infection has become a major health concern that affects travel intention ( Jonas et al., 2010 ). According to Richter (2003) , it is important to recognize the threat of global public health to tourism, which can lead to great uncertainty in people’s future travel intentions and motivations. The most significant related concern centers on the inhibition of tourism demand and the obstacles to tourists’ travel planning decisions as a result of the outbreak of infectious diseases ( Kuo et al., 2008 ).

One of the most popular research topics has been the extensive impact of the pandemic on the tourist behavior, including travel intention and motivation ( Sánchez-Cañizares et al., 2021 ). Unlike previous studies that have focused on the dark side of the pandemic, this study explores the impact of people’s perceptions of positive information related to COVID-19 on their travel motivations and intentions. The positive information of COVID-19 refers to the information that indicates the positive changes of the pandemic situation, including news regarding declining death and infection rates, news about successful vaccination drives, news of re-openings of transportations, news of re-openings of visitor attractions, and so on.

This study selected one significant tourism market segment in China, Chinese university students, as its research object. University students’ travel intentions and motivations have attracted previous scholarly attention ( Kim et al., 2012 ). Deng and Ritchie (2018) classified the risks perceived by university students during traveling into human-made, social-psychological, financial, and health categories. When these risks are perceived to be increasing in the tourism destination, students’ travel intentions decrease due to health and safety concerns ( Hartjes et al., 2009 ). However, on the other hand, university students are young and “allocentric” therefore tending to be risk-takers and crisis-resistant tourists ( Hajibaba et al., 2015 ). Do university students’ risk perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic impact their travel motivations and intentions? If the information perception is positive, will they be willing to travel? This study aims to explore these questions.

As the first country to report cases of COVID-19, China was selected as the research context. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, information about the epidemic has infiltrated the daily life of the Chinese. Apart from the complete closure of China’s tourism industry during the initial stage, the principle of limited and orderly opening has been adopted since April 8, 2020, after the pandemic was gradually controlled. Meanwhile, Chinese university students have been forced to stay at home for a long time due to the lockdown that has been enforced. Their chances of travel have been reduced, and their travel motivation was suppressed. Consequently, they may be more eager to travel and pay more attention to information related to the pandemic, especially positive information. Thus, to understand whether university students are willing to travel during the pandemic, this study explores the impact of perceptions of positive COVID-19 information on travel intentions and motivations. Due to outbound travel has been restricted in China since the break of COVID-19 pandemic, travel in the present study refers to domestic travel only.

Materials and Methods

Research design.

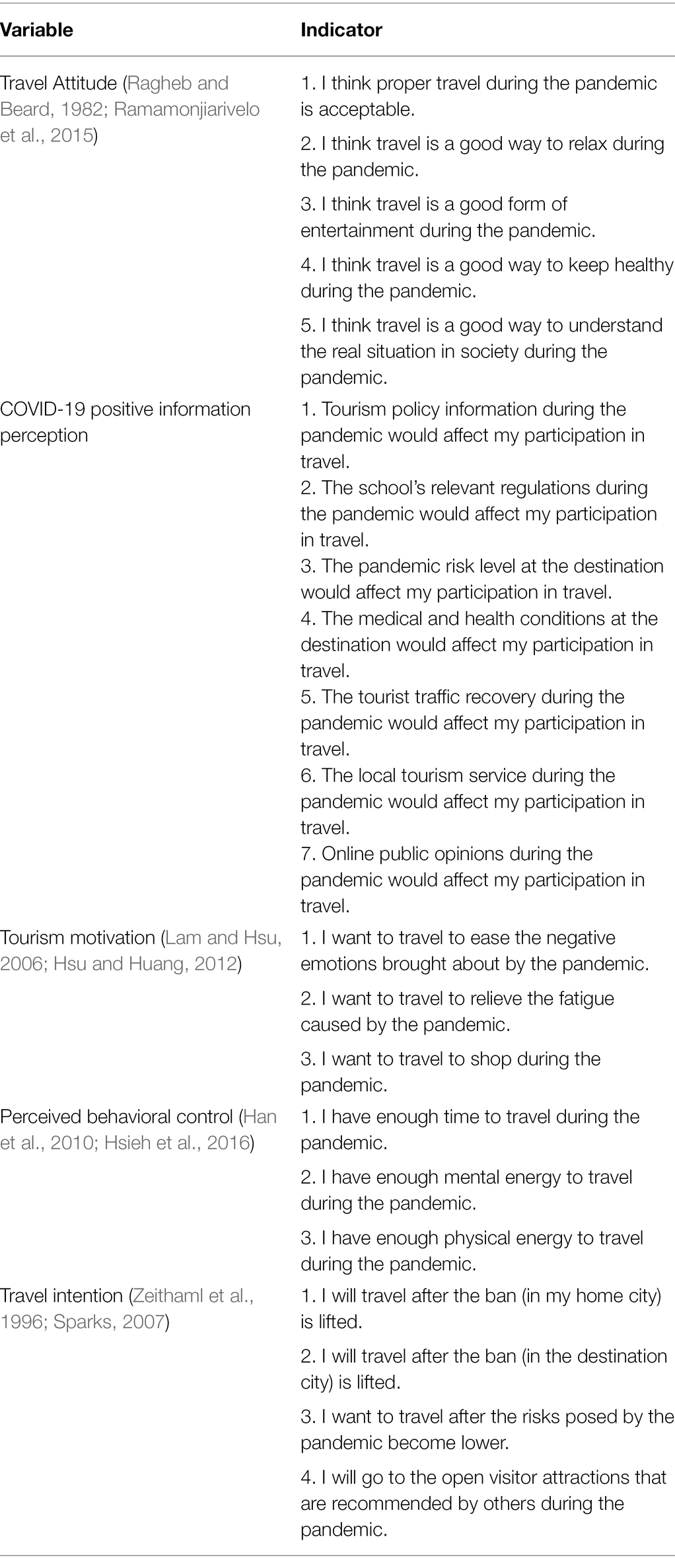

A questionnaire was designed based on the literature and the background of the COVID-19 pandemic with five dimensions (see Table 1 ). The maximum variance method was used for exploratory factor analysis, and items with a factor load less than 0.6 were excluded. A seven-point Likert scale was adopted, in which 1 represented “strongly disagree” and 7 represented “strongly agree.”

Table 1 . Research variables of the survey.

We used the Questionnaire Star online questionnaire system 1 to sample Chinese university students from November 20 to 30, 2020. The link of the online questionnaire was distributed to university students’ WeChat (the most popular social media in China) groups. A total of 470 effective questionnaires out of 500 were collected, with an effective recovery rate of 94%. The questionnaire included four descriptive questions on the students’ gender, grade, risk level in the region, and intended travel mode during the pandemic. SPSS 22.0 and AMOS 21.0 software were used for data analysis to explore the relationships among the various factors.

Literature Review

Travel motivation.

Scholars have divided the dimensions of travel motivation in different ways in the context of different theories. Yüksel et al. (2005) believed that escape, relaxation, enhancing mutual relationships, and self-realization and progress were tourists’ core motivations. According to Lee et al. (2004) , motivations for tourism mainly include cultural attractions, family reunions, curiosity, attraction to local festivals, and the desire for emotional satisfaction. Travel motivations may vary among different tourists, especially those from different countries and cultural backgrounds ( Kim and Prideaux, 2005 ). Travel motivation is also influenced by different values. People with internal values are more eager to visit new tourist sites, while people with external values are more concerned about the on-site experience and the excitement they gain from it ( Li and Cai, 2012 ).

In the face of the sudden outbreak of a disease, people may decrease their travel motivations and concern about protecting themselves ( Zheng et al., 2021 ). The COVID-19 pandemic has aroused people’s increased desire for safety ( Rettie and Daniels, 2020 ), resulting in taking several measures to protect themselves, such as avoiding going out or visiting only places where there is little risk of infection ( Zheng et al., 2021 ). Therefore, evading disease and danger may become a motivation for traveling ( Kock et al., 2020 ). Qiao et al. (2021) asserted the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and tourists’ self-protection motivations. The present study seeks to investigate how people’s travel motivations are affected by their perceptions of positive COVID-19 information.

Travel Intention

Travel intention has been reported to be influenced by a series of factors. Mohamad et al. (2012) claimed that a destination’s image can affect people’s willingness to visit it. Further, the promotion of destinations may positively affect people’s travel intention due to the lower costs ( Jalilvand et al., 2012 ). Different personalities also lead to different travel intentions. Some people prefer familiar destinations, while others prefer those that are unfamiliar ( Lepp and Gibson, 2008 ). Previous tourism experience is also considered to affect travel intention ( Hsieh et al., 2016 ), and interest in the destination plays a significant role in travel intention and destination choice ( Echtner and Ritchie, 1993 ).

Another factor that can influence travel intention is information. Most tourists use online information to increase their understanding of the destination before traveling ( Narangajavana et al., 2017 ), and searching for information about the destination is considered a common process in tourism decision making ( Amaro et al., 2016 ). Positive information, such as good E-WOM (electronic word-of-mouth), increases potential tourists’ travel intentions ( Jalilvand et al., 2012 ). In contrast, negative information (e.g., information about risks) may decrease travel intentions ( Beerli et al., 2007 ). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, tourists’ travel intentions are more related to the information about epidemic situation and related regulations of their destinations. The information available on the COVID-19 pandemic from different channels (e.g., news, social media, relatives, and friends) has tended to be extremely negative, especially in the early stage, and the emotional anxiety and fear caused by this information have led people to give up their travel plans ( Bae and Chang, 2021 ).

The relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and travel intention has been investigated by several studies. Luo and Lam (2020) found that fear of COVID-19 directly affects travel anxiety and risk attitude, which have direct negative effects on travel intention. Riestyaningrum et al. (2020) found that the pandemic had significant partial effects on international tourists’ travel intentions. Zenker et al. (2021) tested how tourists’ travel intentions are affected by their intra-personal anxiety. Zheng et al. (2021) asserted that travel intentions are influenced by tourists’ evaluation of the risks and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, these studies have tended to focus on the impact of negative information about the COVID-19 pandemic on travel intentions, while little attention has been paid to the possible positive changes to travel intention that may occur when the situation improves. Thus, to complement the existing literature, this study explores the influence of perceptions of positive COVID-19 information on travel intention.

Information Perception

The influence of information perception on travel decisions has been confirmed by previous studies ( Fan et al., 2018 ; Gössling et al., 2020 ). Before traveling, people search for relevant information about the destination in advance ( Nunkoo et al., 2013 ). When people have a positive view of the information about a destination, their travel intention to this destination is stimulated ( Woodside et al., 2011 ). However, when people perceive risks in a destination, the fear they feel further increases their self-protection motivations ( Zheng et al., 2021 ). Once this perception of risks exceeds their psychological endurance, tourists may give up their travel plans altogether. This is consistent with the Basic Emotion Theory, which is central to the study of emotional expression, stating that emotions enable the individual to respond adaptively to evolutionarily significant threats and opportunities in the environment ( Keltner et al., 2019 ).

Rittichainuwat and Chakraborty (2009) found that infectious diseases negatively impact tourists’ travel intentions due to the potential health risks they pose. The information on the associated risks will further determine whether people have enough driving force to travel. Tourists’ perceptions of risk information further aggravate the psychological barriers to travel to risky areas ( Rittichainuwat and Chakraborty, 2009 ). The unique characteristics of COVID-19 have altered the risk perceptions associated with destinations ( Jahari et al., 2021 ). Travelers’ risk perception predicts their information-seeking process, which helps them to accumulate the risk information that influences their travel intentions ( Meng et al., 2021 ). Specifically, as a “misinfodemic” ( Williams et al., 2020 ), the negative information portrayed in the mass media regarding the COVID-19 has increased people’s perceptions of the risks of traveling and their self-protection motivations ( Qiao et al., 2021 ). Consequently, people have reduced their travel to protect their health during the pandemic ( Yang et al., 2020 ).

However, that is not to say that people are unwilling to travel during the pandemic. People may generate positive travel intention even if they are in fear of COVID-19 ( Yang et al., 2022 ). As Itani and Hollebeek (2021) revealed, visitors’ virtual reality tourism intentions increased when in-person travel was not feasible. Travel motivations and intentions that were suppressed by the pandemic will be liberated when the situation improves. The situation may also lead some people to pay special attention to the positive information related to the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Lu et al. (2021) , people tended to seek COVID-19-related information from social media platforms where positive content was prevalent. They perceived these positive contents as desirable and necessary due to the positive impact on their emotions. Seeking further information is a common tourist strategy to reduce perceived risks ( Reichel et al., 2009 ). According to Kuo et al. (2015) , the perception of reliable, accurate, and easily available information can reduce the risks tourists perceive and stimulate their positive intentions to visit a destination. Furthermore, the public always trust and consider the information as reliable whenever it comes from the government ( Mohammed et al., 2020 ) and their trust on the government could positively influence the risk perception during the pandemic situations ( Tumlison et al., 2017 ). In the Middle East, tourists’ willingness to travel depends on their sense of security and government policies, as well as whether a vaccine against COVID-19 is available ( Choufany, 2020 ). Ivanova et al. (2021) found that the health system and disinfection status of a destination also affect tourists’ destination choice. Qiao et al. (2021) investigated the role of positive mass media coverage in decreasing tourists’ self-protection motivations. Wang et al. (2021) found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, a low-risk perception has a positive influence on tourists’ attitude toward undertaking regional travel. The above studies have indicated that, as an “infodemic” ( Williams et al., 2020 ), reliable and positive information on the COVID-19 pandemic may play a role in enhancing people’s travel intentions.

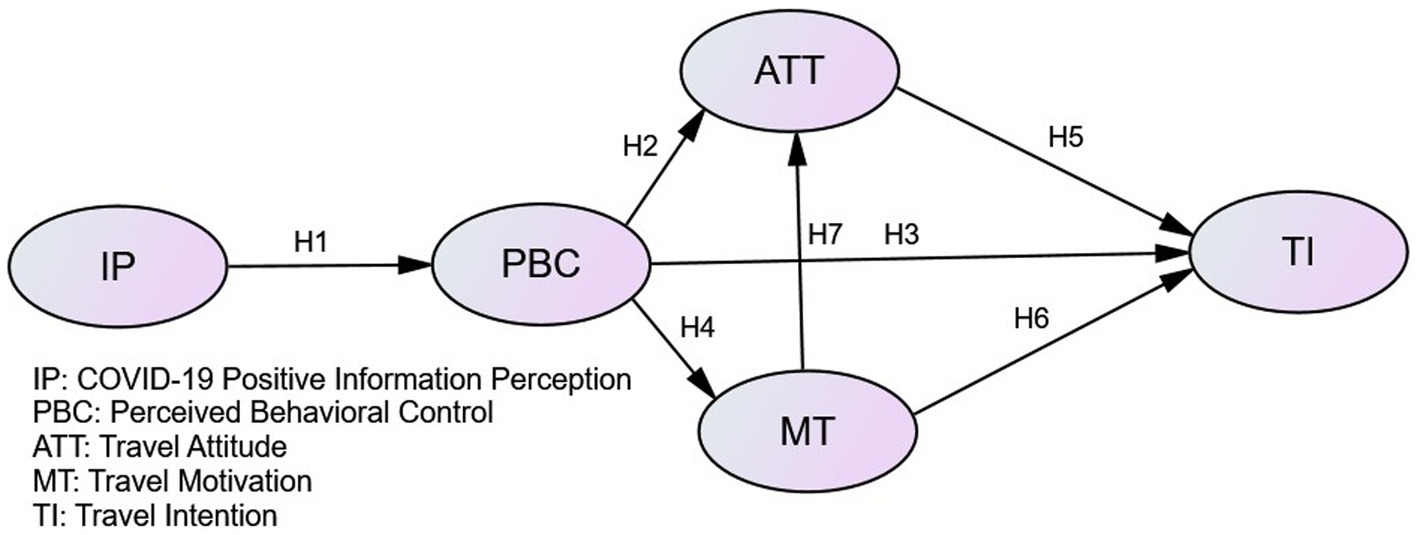

The Theory of Planned Behavior in Tourism

According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, people’s behavior is not only determined by their will but also by their attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control ( Ajzen, 1991 ). This theory has been widely used in tourism research. Jalilvand et al. (2012) studied the influence of E-WOM on the choice of tourism destination by using the theoretical model of planned behavior. Sparks and Pan (2009) also revealed that subjective norms and perceived behavioral control were related to Chinese tourists’ choice of Australian destinations. Further, based on the Theory of Planned Behavior, Bamberg et al. (2003) investigated how tourists’ choice of travel mode is affected by their past behaviors, habits, and the information they have.

The application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to investigating travel intention has presented inconsistent findings. Lam and Hsu (2006) demonstrated that attitude and perceived behavioral control are factors that can effectively predict travel intention. Lee and Jan (2018) showed that environmental attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control have a positive impact on ecotourism intention. However, Sparks and Pan’s (2009) study suggested that the reasons behind different travel intentions may not be attributed to attitude and perceived behavioral control but rather to subjective norms. This indicates the necessity to test if the constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior are effective in influencing people’s travel intentions during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Sánchez-Cañizares et al. (2021) revealed the modulating effect of perceived risks on travel intention in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Lucarelli et al. (2020) demonstrated that the construct relationships in the Theory of Planned Behavior were not weakened by the COVID-19 pandemic and that those who have good knowledge of COVID-19 and climate change exhibit higher pro-environmental behavioral intentions.

Specifically, Li et al. (2021) explored the significant changes in post-pandemic planned travel behaviors, finding that Chinese tourists’ travel intentions would still be negatively influenced even 6 months or longer after the COVID-19 pandemic was controlled. However, they did not take into account the quality and reliability of the information available, which may mediate the negative influence of perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel intention. Moreover, their research was conducted at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak (February 9, 2020) when people were overwhelmed by fears and worries during the initial quarantine. In contrast, the present study was conducted at the end of 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic was under control in China and the country’s tourism industry had reopened. Contrary to the frightening information available in the early stage, the information available on the pandemic in China tended to be positive then, with few deaths and new cases of infection reported. With more knowledge and positive information about the COVID-19 pandemic, people’s travel intentions may be increased, and this study explores this issue in the framework of the Theory of Planned Behavior. However, we did not include the variable of subjective norms in our framework due to inadequate theoretical support in existing studies.

Since tourism is an information-intensive industry, accurate information input is an important factor for tourists’ destination choice ( Lam and McKercher, 2013 ). Information on the current situation of the COVID-19 pandemic and the tourism industry can affect tourists’ personal cognition and subjective judgment. As previous studies have indicated ( Reichel et al., 2009 ; Rittichainuwat and Chakraborty, 2009 ; Kuo et al., 2015 ), the more positive and reliable the information tourists receive, the fewer challenges and risks they perceive, and the more they perceive they can control of their travel behaviors. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1) : University students’ perceptions of the positive information on the COVID-19 pandemic have a positive impact on their perceived behavioral control of travel.

Han et al. (2010) observed that attitude is an important mediator between perceived behavioral control and behavioral intention. Perceived behavioral control also affects travel intention Hsu and Huang (2012) . In addition, travel motivation is determined by tourists’ feelings and value system ( Gnoth, 1997 ), which are also related to perceived behavioral control. The more tourists perceive they can control a situation, the stronger their travel motivation will be; thus, tourists’ willingness to travel to risky destinations is affected by how much they perceive they can control their behaviors in terms of the risks posed ( Jonas et al., 2010 ). In this way, tourists traveling shorter distances from home or to familiar destinations would feel safer during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Galoni et al., 2020 ) due to their stronger perceived behavioral control. Research has further shown that the risk of COVID-19 infection affects travel intention through perceived behavioral control ( Sánchez-Cañizares et al., 2021 ). Therefore, this study proposed the following additional hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2 (H2) : University students’ perceived behavioral control has a positive impact on their travel attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hypothesis 3 (H3) : University students’ perceived behavioral control has a positive impact on their travel intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hypothesis 4 (H4) : University students’ perceived behavioral control has a positive impact on their travel motivations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As shown by Nunkoo et al. (2013) , people’s travel intentions are related to their travel attitudes. When people have a positive attitude toward travel, they will also have positive travel intentions ( Shen et al., 2019 ). Hsu and Huang (2012) also showed that travel motivation is an important predictor of travel intention. Therefore, Hypotheses 5 and 6 were proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 5 (H5) : University students’ travel attitudes have a positive impact on their travel intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hypothesis 6 (H6) : University students’ tourism motivations have a positive impact on their travel intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hsu and Huang (2012) verified that people’s motivation for travel affects their attitude toward it, while Mansour and Mumuni (2019) used the push-pull theory to demonstrate the impact of motivation on attitudes toward domestic tourism. Therefore, Hypothesis 7 was proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 7 (H7) : University students’ travel motivations have a positive impact on their travel attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

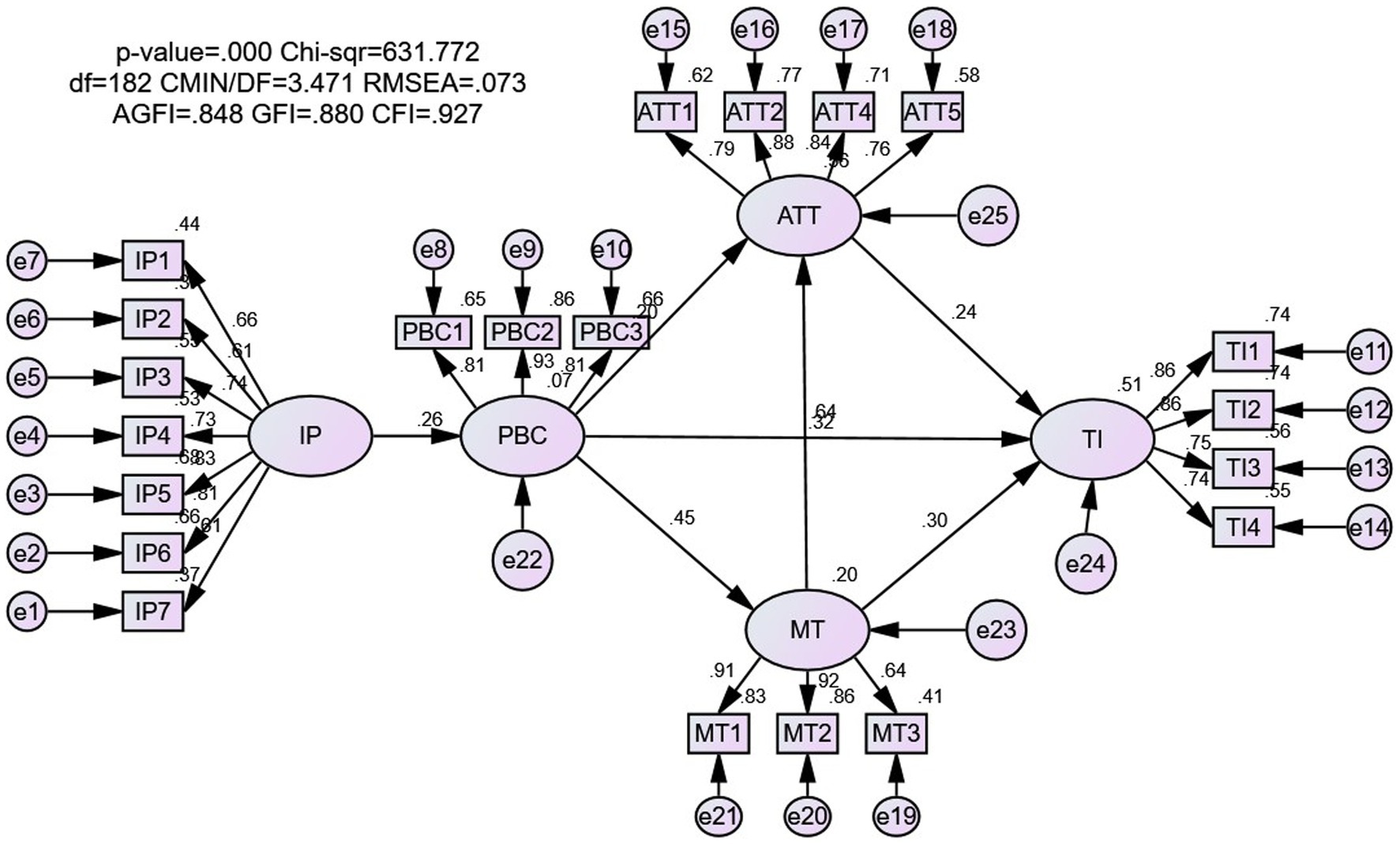

Based on the above hypotheses, a preset model was established, as shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1 . Conceptual model.

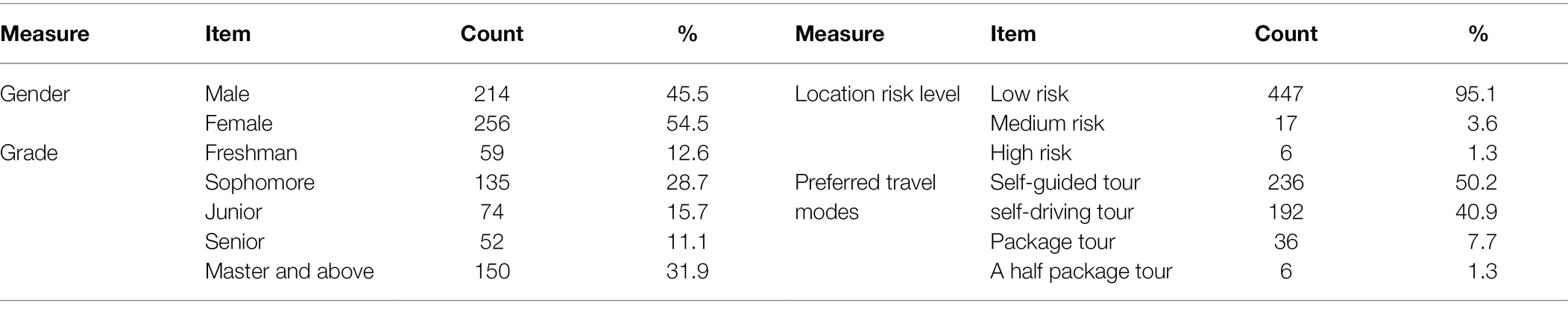

Demographic Information

The descriptive data are shown in Table 2 . The sample comprised both male and female students, ranging from freshmen to postgraduate students. The location risk level is defined by the New Coronavirus Pneumonia Prevention and Control Program released by the National Health Committee of the People’s Republic of China. Specifically, low-risk regions: no confirmed cases or no new confirmed cases for 14 consecutive days; medium risk regions: there are new confirmed cases within 14 days, the cumulative confirmed cases are no more than 50, and there is no aggregated epidemic within 14 days; and high risk regions: there are more than 50 confirmed cases in total, and there is an aggregated epidemic situation within 14 days.

Table 2 . Descriptive statistics ( N = 470).

Reliability and Validity Analysis

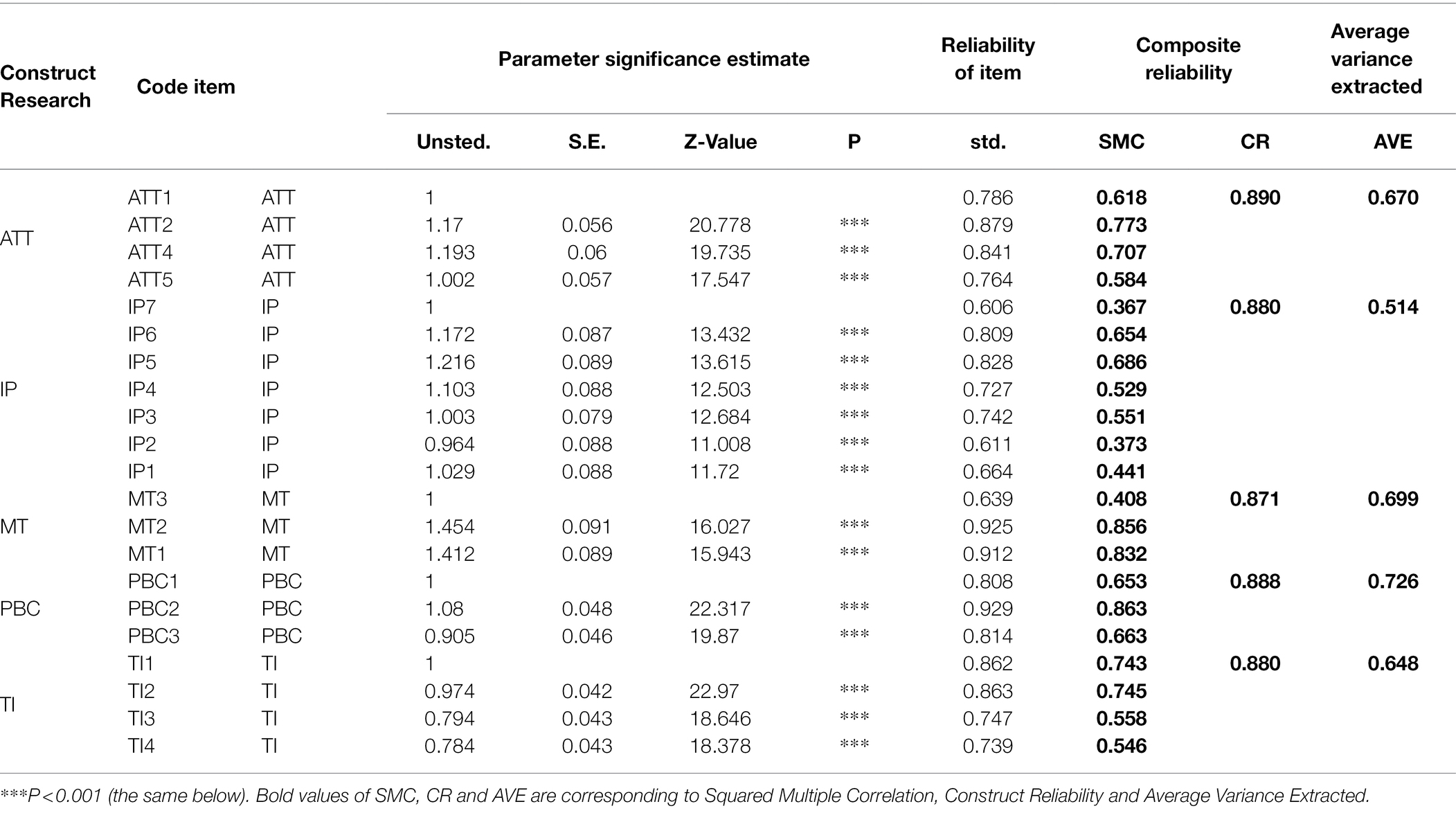

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to extract the questionnaire, and Caesar’s normal maximum variance method was used to rotate the questionnaire ( Joreskog and Sorbom, 1989 ). The MT4 was deleted since the factor load in this scale was less than 0.60, and 22 valid questions were retained. The reliability and validity analysis showed that the factor load of each dimension was between 0.610 and 0.930, which met the requirements of the model.

The Cronbach’s α values ranged from 0.626 to 0.856, the component reliability ranged from 0.871 to 0.890, and the average variance extraction value ranged from 0.514 to 0.726 ( Tables 3 and 4 ); thus, the reliability of all items met the requirements. The average variance extraction value (AVE) of each dimension was between 0.572 and 0.643. The parameter estimation of each measurement model and topic was significant, that is, p < 0.001. Therefore, the five subscales reached the ideal standard of reliability and aggregate validity.

Table 3 . Measurement model.

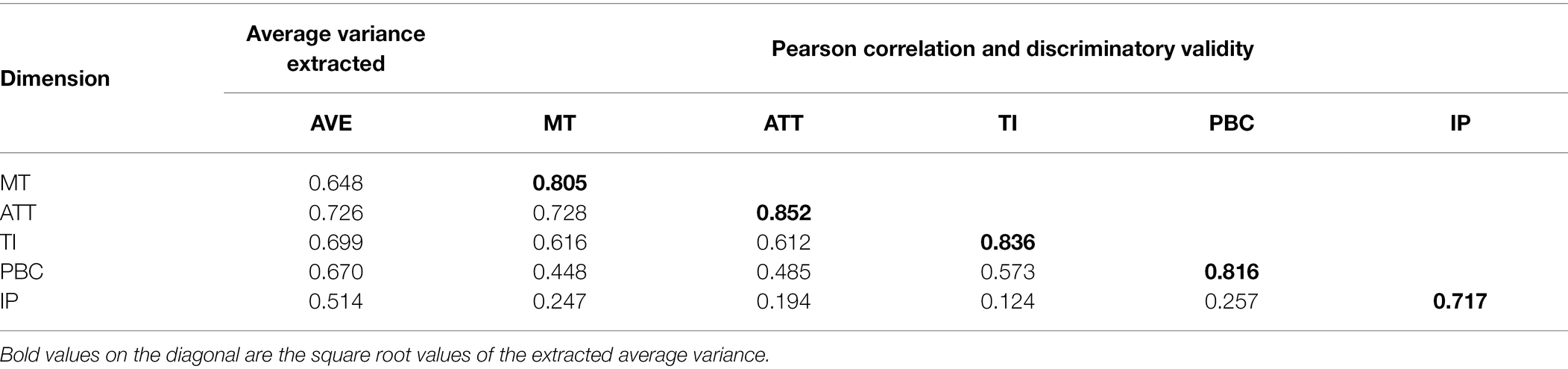

Table 4 . Discriminatory validity.

The square root of AVE was greater than the Pearson correlation coefficient between the dimensions below the diagonal, indicating each dimension had significant difference validity ( Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ).

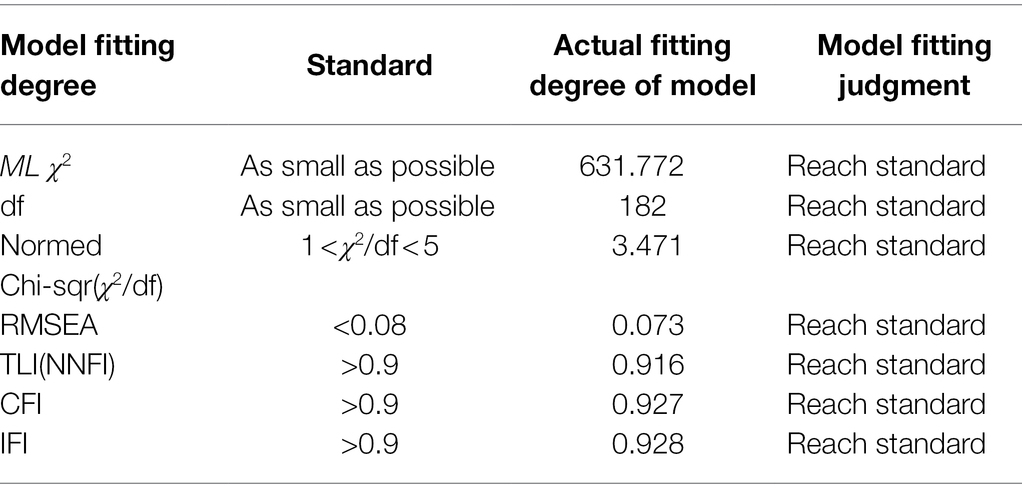

Measurement Model Fit Test

According to Abd-El-Fattah (2010) , the better the model fit, the closer the sample data and the model matrix. Both the absolute fit index and the relative fit index were used in the model fit test. The ratio of the chi-square value to the degree of freedom ( χ 2 /df) eliminates the influence of the degree of freedom, and it is acceptable when less than 5. As shown in Table 5 , the value of χ 2 /df was 3.471, the value of RMSEA was lower than 0.08. Although the values of GFI and AGFI were less than 0.9, they are close to 0.9 (0.848 and 0.880), which were also within the allowable range, as recommended by Hair et al. (1998) . The relative fit indices usually include CFI, IFI, and NNFI, which were all higher than 0.9 in this study. Overall, this study’s model had a good fit.

Table 5 . Index table of SEM model fitness.

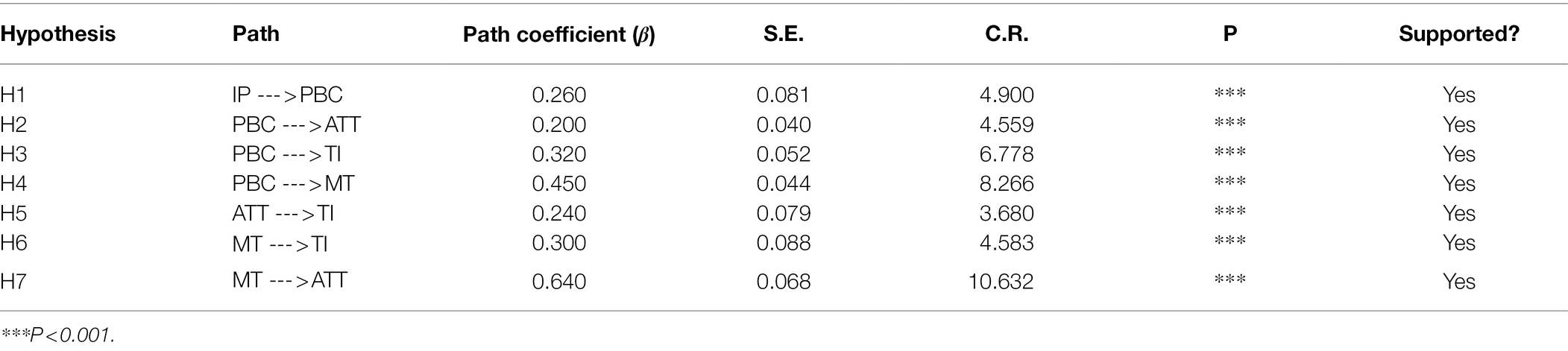

Hypothesis Testing

As shown in Figure 2 and Table 6 , the path coefficients β of the seven hypotheses were all greater than 0.20, and the values of p were all less than 0.001, reaching a significant level and indicating that the seven hypotheses were all verified.

Figure 2 . Measurement and structural model analysis.

Table 6 . Outcomes of structural equation modeling analysis ( N = 470).

Analysis of the Mediating Effect

The bootstrap method and Sobel Z test were used to test the mediating effect ( Table 7 ). The indirect effect of perceptions of positive COVID-19 information on travel intention through perceived behavioral control was 0.108 (SE = 0.027, Z = 4 > 1.96, p = 0.000 < 0.05). Further, the upper and lower limits of bias-corrected 95% CI and percentile 95% CI did not contain 0; therefore, the indirect effect was confirmed. The indirect effect of perceptions of positive COVID-19 information on travel intention through perceived behavioral control and travel attitude was 0.016 (SE = 0.008, Z = 2 > 1.96, p = 0.007 < 0.05); through perceived behavioral control and travel motivation was 0.045 (SE = 0.020, z = 2.25 > 1.96, p = 0.000 < 0.05); and through perceived behavioral control, travel motivation, and travel attitude was 0.023 (SE = 0.001, Z = 2.3 > 1.96, p < 0.05).

Table 7 . Intermediary effect test table.

Among the indirect effects, perceptions of positive COVID-19 information had the largest mediating effect on travel intention through perceived behavioral control. However, the direct effect in this study was not significant, indicating that perceptions of positive COVID-19 information had a complete mediating effect on travel intention through perceived behavioral control, travel attitude, and travel motivation.

Discussion and Conclusion

Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior and the background of the COVID-19 pandemic, this study reveals that perceptions of positive COVID-19 information positively impacted Chinese university students’ perceived behavioral control, while their perceived behavioral control had a positive impact on their travel attitudes, motivations, and intentions. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies that have demonstrated the negative impact of environmental risks on travel intention ( Rittichainuwat and Chakraborty, 2009 ; Quintal et al., 2010 ) and the role of positive information perception in stimulating tourists’ travel intentions ( Kuo et al., 2015 ; Choufany, 2020 ; Ivanova et al., 2021 ). The more positive COVID-19 information tourists obtained from various sources, the more they perceived they could control their travel-related behavior. On one hand, positive news related to COVID-19 decreased the university students’ risk perceptions, self-protection motivations, and fear of traveling ( Qiao et al., 2021 ). On the other, the re-opening of transportation, visitor attractions, and tourism services assured the feasibility of traveling ( Puca et al., 2020 ).

Positive COVID-19 information perceptions had no direct influence but did display a complete mediating effect on travel intention through perceived behavioral control, attitude, and motivation. This result is in accordance with Zhu and Deng (2020) , who revealed that available information indirectly influenced people’s intention to travel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, this study also confirmed the mediating effect of perceived behavioral control on travel intention ( Sánchez-Cañizares et al., 2021 ). Scholars have previously verified that negative information causes emotional anxiety and fear, thus lowering perceived behavioral control and further lowering travel motivation and intention ( Bae and Chang, 2021 ; Zheng et al., 2021 ). In contrast, our study confirmed the positive role that positive COVID-19 information plays in enhancing travel motivation and intention, echoing Tavitiyaman and Qu (2013) .

Our finding contradicts with Li et al.’s (2021) conclusion that people’s travel intentions would still be negatively influenced 6 months or even longer after the COVID-19 pandemic was controlled. Lengthy lockdowns lead to both physical and psychological needs for leisure and escape. As long as the COVID-19 pandemic is under control, more positive information is perceived, and people’s perceived behavioral control is enhanced. This leads to positive attitudes toward travel, the release of suppressed travel motivation, and, ultimately, the increase of travel intention. This was particularly obvious among the Chinese university students who had been forced to stay at home and take classes online for a long time. They paid special attention to any positive information regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and the tourism industry. With increased perceived behavioral control, they generated positive travel attitudes, motivations, and intentions, which can transform into actual travel once other preconditions (e.g., time and money) are met. At present, the pandemic is under control in China and some other countries, and the tourism industry is gradually recovering. We believe that COVID-19 will be controlled in the near future as governments adopt relevant measures and the gradual use of vaccines. According to the results of this study, with perceptions of more positive information about the pandemic’s progress, people’s travel intention will be increased.

Implications

We investigated the travel motivation and intention of Chinese university students during the tourism industry’s recovery from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, adding the variable of positive information perceptions to the relationship between the pandemic and tourism for the first time. First, this study contributes to our understanding of the potential recovery of the tourism industry during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. While previous studies mainly focused on the dark side of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel motivation and intention, our study fills the knowledge gap of the bright side of positive COVID-19 information. The COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to alter the ways in which tourists assess risks and form their risk perception ( Jahari et al., 2021 ). Different from the general positive information perception (e.g., good service quality), COVID-19 positive information perception relates to travelers’ first priority health and safety. It decreases travelers’ emotional anxiety and fear for pandemic, which is the decisive factor of travel motivation and travel intention. Second, our study also enriches the research on university students’ travel motivations and intentions in terms of the impacts of risk and information perceptions. Previous studies have confirmed university students’ travel intentions would decrease in face of risks ( Hartjes et al., 2009 ; Kim et al., 2012 ). The findings in this study reveal that university students are risk-takers and crisis-resistant tourists ( Hajibaba et al., 2015 ) when the information they perceive is positive. Third, it extends the application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in the tourism research by adding the dimension of positive information perceptions. It asserts the effectiveness of the Theory of Planned Behavior in predicting tourists’ intention and behavior.

This study also offers some practical implications. According to the results, perceptions of positive COVID-19 information mainly affect travel intention through perceived behavioral control. Therefore, tourism operators should take measures to increase undergraduate students’ perceived behavioral control, thereby increasing their travel intentions. This includes delivering various positive information to undergraduate students, including the positive COVID-19 situation at destinations, the measures taken in these destinations to prevent infection, the tourism services provided, and so on. Corresponding measures should be taken to strengthen the use of technology from the perspective of information perception, especially in this special period, to ensure the wide circulation and authenticity of information. Some smart phone applications which are popular among Chinese undergraduate students (e.g., WeChat and Douyin) should be paid special attention. Tourism managers can spread relevant security information about the COVID-19 pandemic prevention measures that potential tourists may pay attention to. During travel, tourism operators should also employ measures to reduce the risks of tourists’ exposure to infection, such as improving sanitation and disinfection services, strictly controlling the number of tourists entering visitor attractions, and offering different viewing routes designed to divert tourists and avoid the formation of crowds.

Limitations and Future Research

Due to the time limitation and impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, only 470 valid samples were collected online. Future research should expand the scope of this study’s survey and the sample size and improve the quality of the data collection by distributing questionnaires both online and offline. Although the questionnaire showed good reliability and validity within the acceptable range, this study only explored travel motivation and intention based on the components of the theory of planned behavior, while overlooking other influencing factors. Future research should include these other influencing factors, based on other theories, to investigate the impact of positive COVID-19 information perceptions on travel motivation and intention.

Furthermore, the survey was limited to China, where the pandemic has been controlled to a large extent. Consequently, most respondents were from low-risk areas, and many of them had recently undertaken tourism activities. The results may differ in countries where the pandemic situation is still critical. Moreover, as Kaczmarek et al. (2021) noted, collectivist countries have tended to cope better with the pandemic, and China is a good example of this. Government control has played a significant role in tourism recovery during the pandemic ( Fong et al., 2021 ), and their trust in the government may increase Chinese tourists’ travel intentions by decreasing their fear ( Zheng et al., 2021 ). Future research should be undertaken in other more individualist countries to determine if the results differ. In addition, the sample of this study is Chinese university students who are “allocentric” and rely on their parents’ economic support for travel, which limits its findings to be generalized. The respondent sample should be extended to other groups, such as the elderly, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between positive COVID-19 information perceptions and travel intention.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for the study of human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This paper is supported by the National Social Science Fund projects “The research on intelligent elderly care service mode of sports and medicine integration” (no. 21XTY006).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ www.wjx.cn

Abd-El-Fattah, S. M. (2010). Garrison’s model of self-directed learning: preliminary validation and relationship to academic achievement. Span. J. Psychol. 13, 586–596. doi: 10.1017/s1138741600002262

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Amaro, S., Duarte, P., and Henriques, C. (2016). Travelers’ use of social media: a clustering approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 59, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.03.007

Bae, S. Y., and Chang, P. J. (2021). The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (covid-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (march 2020). Curr. Issue Tour. 24, 1017–1035. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1798895

Bamberg, S., Ajzen, I., and Schmidt, P. (2003). Choice of travel mode in the theory of planned behavior: the roles of past behavior, habit, and reasoned action. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 25, 175–187. doi: 10.1207/S15324834BASP2503_01

Beerli, A., Meneses, G. D., and Gil, S. M. (2007). Self-congruity and destination choice. Ann. Tour. Res. 34, 571–587. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2007.01.005

Choufany, H. M., (2020). HVS COVID-19: travelled and hotel guest sentiment findings Middle East. Available at: https://www.hvs.com/article/8766-hvs-covid-19-traveller-and-hotelguest-sentiment-findings-middle-east (Accessed July 3, 2021).

Google Scholar

Deng, R., and Ritchie, B. W. (2018). International university students’ travel risk perceptions: an exploratory study. Curr. Issue Tour. 21, 455–476. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2016.1142939

Echtner, C. M., and Ritchie, J. R. B. (1993). The measurement of destination image: an empirical assessment. J. Travel Res. 31, 3–13. doi: 10.1177/004728759303100402

Fan, V. Y., Jamison, D. T., and Summers, L. H. (2018). Pandemic risk: how large are the expected losses? Bull. World Health Organ. 96, 129–134. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.199588

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fong, L. H. N., Law, R., and Ye, B. H. (2021). Outlook of tourism recovery amid an epidemic: importance of outbreak control by the government. Ann. Tour. Res. 86:102951. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102951

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Galoni, C., Carpenter, G. S., and Rao, H. (2020). Disgusted and afraid: consumer choices under the threat of contagious disease. J. Consum. Res. 47, 373–392. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucaa025

Gnoth, J. (1997). Tourism motivation and expectation formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 24, 283–304. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(97)80002-3

Gössling, S., Scott, D., and Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 29, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., and Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis. 5th Edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hajibaba, H., Gretzel, U., Leisch, F., and Dolnicar, S. (2015). Crisis-resistant tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 53, 46–60. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.04.001

Han, H., Hsu, L., and Sheu, C. (2010). Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 31, 325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.013

Hartjes, L. B., Baumann, L. C., and Henriques, J. B. (2009). Travel health risk perceptions and prevention behaviors of US study abroad students. J. Travel Med. 16, 338–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00322.x

Hsieh, C. M., Park, S. H., and Mcnally, R. (2016). Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to intention to travel to Japan among Taiwanese youth: investigating the moderating effect of past visit experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 33, 717–729. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2016.1167387

Hsu, C., and Huang, S. (2012). An extension of the theory of planned behavior model for tourists. J. Hospitality Tourism Res. 36, 390–417. doi: 10.1177/1096348010390817

Itani, O., and Hollebeek, L. (2021). Light at the end of the tunnel: Visitors’ virtual reality (versus in-person) attraction site tour-related behavioral intentions during and post-COVID-19. Tour. Manag. 84:104290. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104290

Ivanova, M., Ivanov, I. K., and Ivanov, S. H. (2021). Travel behaviour after the pandemic: the case of Bulgaria. Anatolia 32, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2020.1818267

Jahari, S. A., Yang, I., French, J. A., and Ahmed, P. K. (2021). Covid-19 and beyond: understanding travel risk perception as a process. Tour. Recreat. Res. , 1–16. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2021.1937450

Jalilvand, M. R., Samiei, N., Dini, B., and Yaghoubi, M. P. (2012). Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination and travel intention: an integrated approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 1, 134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.001

Jonas, A., Mansfeld, Y., Paz, S., and Potasman, I. (2010). Determinants of health risk perception among low-risk-taking tourists traveling to developing countries. J. Travel Res. 50, 87–99. doi: 10.1177/0047287509355323

Joreskog, K. G., and Sorbom, D. (1989). A Guide to the Program and Applications. Chicago: SPSS Inc.

Kaczmarek, T., Perez, K., Demir, E., and Zaremba, A. (2021). How to survive a pandemic: the corporate resiliency of travel and leisure companies to the COVID-19 outbreak. Tour. Manag. 84:104281. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104281

Keltner, D., Sauter, D., Tracy, J., and Cowen, A. (2019). Emotional expression: advances in basic emotion theory. J. Nonverbal Behav. 43, 133–160. doi: 10.1007/s10919-019-00293-3

Kim, K., Hallab, Z., and Kim, J. N. (2012). The moderating effect of travel experience in a destination on the relationship between the destination image and the intention to revisit. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 21, 486–505. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2012.626745

Kim, S. S., and Prideaux, B. (2005). Marketing implications arising from a comparative study of international pleasure tourist motivations and other travel-related characteristics of visitors to Korea. Tour. Manag. 26, 347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.022

Kock, F., Nørfelt, A., Josiassen, A., Assaf, A. G., and Tsionas, M. G. (2020). Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: the evolutionary tourism paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 85:103053. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103053

Kumar, V., Alshazly, H., Idris, S. A., and Bourouis, S. (2021). Evaluating the impact of covid-19 on society, environment, economy, and education. Sustainability 13:13642. doi: 10.3390/su132413642

Kuo, H. I., Chen, C. C., Tseng, W. C., Ju, L. F., and Huang, B. W. (2008). Assessing impacts of SARS and Avian Flu on international tourism demand to Asia. Tour. Manag. 29, 917–928. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.10.006

Kuo, P. J., Zhang, L., and Cranage, D. A. (2015). What you get is not what you saw: exploring the impacts of misleading hotel website photos. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 27, 1301–1319. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2013-0532