If you’ve ever tried to faithfully recreate the graphics seen on Star Trek , you know that the distinctive typography requires just the right fonts. I’ve found quite a few useful ones at various websites over the years. Whether it’s a movie title, a computer interface, or an alien script you’re looking to illustrate, there’s probably a font here to get you started. The fonts collected below aren’t supposed to be a complete archive of every font available, but rather a source for the best and most useful versions that are out there.

I’ve used many of these fonts to create various graphics for Star Trek Minutiae over the years, from the You’re the Admiral! maps to that time this site was assimilated by the Borg . I hope you find these useful, too!

Archivist’s Note: These fonts have been obtained through various free download websites. All fonts are copyrighted by their original creators.

Title Fonts

Download All

Alien Fonts

External Links

- Memory Alpha’s list of Star Trek fonts

- Star Trek Fonts from FontSpace

- Star Trek Fonts from MyFonts

- Typography: The Final Frontier from FontShop

Star Trek Font: A Guide to Its Origins and Usage

Star Trek, the iconic science fiction franchise that has captivated audiences for over five decades, is popular for its innovative and futuristic storytelling and distinctive visual style. One element contributing to the show’s unique aesthetic is its font, commonly called the “Star Trek font.” This bold and futuristic typeface has become synonymous with the franchise and is instantly recognizable to fans worldwide. However, this font’s origin has been a debate among Trekkies.

We will delve into the history of the Star Trek font, exploring its creation, evolution, and the controversy surrounding its use. From its early appearances in the original series to its prominent role in modern adaptations, we will uncover the truth behind this iconic font and its enduring impact on the Star Trek universe.

Table of Contents

What Is Star Trek Font?

Star Trek Font refers to the typography used in the iconic Star Trek franchise. The font is popular for its futuristic and sleek appearance, reflecting the sci-fi theme of the series. Clean lines, sharp angles, and a modern aesthetic often characterize it.

The Star Trek Font has become popular among fans and designers, who use it to create various Star Trek-themed graphics, merchandise, and promotional materials. Whether you’re a die-hard Trekkie or simply appreciate the unique style of the font, incorporating it into your designs can add an extra touch of intergalactic flair.

History Of The Font

The Star Trek font has become iconic in popular culture and instantly recognizable to fans of the beloved science fiction franchise. The font used in the Star Trek logo and title sequences is popular as “Helvetica Inserat” and was chosen for its futuristic and sleek appearance.

Created by Swiss typeface designer Max Miedinger in 1957, Helvetica Inserat is a bold and attention-grabbing font that perfectly captures the spirit of exploration and adventure that Star Trek represents. Over the years, the font has undergone minor modifications to enhance legibility and maintain its modern aesthetic. Today, it continues to symbolize the enduring legacy of Star Trek and its impact on popular culture.

Creative Steps To Incorporate The Star Trek Font In Design Projects

The Star Trek font is a beloved and iconic typeface that instantly evokes feelings of adventure and exploration. If you’re looking to incorporate this iconic font into your design projects, there are several creative steps. Incorporating the Star Trek font into design projects can add a touch of sci-fi and nostalgia. Remember to use the font sparingly and ensure it complements other design elements for a cohesive and visually appealing result. Here are some creative steps to use the Star Trek font in your designs:

1. Logo Design: Use the Star Trek font to create a logo for a sci-fi-themed event or business. The bold and futuristic look of the font can instantly convey the theme and attract attention. 2. Poster Design: Incorporate the Star Trek font in poster designs for sci-fi conventions or movie screenings. It can help capture the essence of the Star Trek universe and appeal to fans. 3. Website Design: Use the Star Trek font for headings or titles on a website dedicated to science fiction, space exploration, or technology. It can give a futuristic vibe and enhance the overall visual experience. 4. Social Media Graphics: Create eye-catching graphics using the Star Trek font to promote sci-fi-related content, events, or products.

The Font Used In The Star Trek Wordmark

The Star Trek wordmark’s font is “Star Trek Font.” This font was specifically created for the Star Trek franchise and is designed to resemble the lettering used in the official Star Trek logo. It features angular, futuristic letters that convey a sense of technology and adventure. The Star Trek Font has become iconic and instantly recognizable to the series’ fans.

Many graphic designers and Star Trek enthusiasts enjoy using this font to create their own Star Trek-inspired designs, whether it be for fan art, merchandise, or promotional materials.

How To Download And Use The Font

If you’re a Star Trek fan and want to add a touch of sci-fi to your design projects, you might be interested in using the Star Trek font. Remember to check if there are any usage restrictions or licensing requirements associated with the Star Trek font before using it commercially or for public distribution. Enjoy adding intergalactic flair to your designs with the iconic Star Trek font. To download and use the font, follow these simple steps:

1. Search for a trusted website that offers free Star Trek fonts. There are various websites where you can find and download font for free.

2. Once you’ve found a reliable source, click the download button or link to start the download process. Make sure to save the file in a location on your computer that is easily accessible.

3. After downloading the font file, locate it on your computer and open it. You may need to extract the files from a zip folder before proceeding.

4. Install the font onto your computer by double-clicking on the font file and selecting “Install” when prompted. This will add the Star Trek font to your system’s font library.

5. Now that the font is installed, you can use it in various design software applications such as Adobe Photoshop, Microsoft Word, or any other program that allows you to select custom fonts.

Repurposing Fonts For Commercial Purposes

Repurposing fonts for commercial purposes can be a creative and cost-effective way to enhance your branding and marketing materials. However, ensuring that you have the appropriate licensing rights to use the font in a commercial setting is important. Many fonts are protected by copyright laws, meaning you may need permission from the font creator or purchase a license to use the font commercially.

Additionally, it is important to consider the terms of use for the font, as some creators may have specific restrictions on how their fonts can be handy. By knowing these considerations and obtaining the necessary permissions or licenses, you can confidently incorporate repurposed fonts into your commercial endeavours.

How To Design Your Font

Designing your own Star Trek font can be a fun and creative project. Whether you’re a fan of the iconic Star Trek series or just looking to add a unique touch to your design work, creating a custom font can help you stand out. Here are some steps to help you get started:

1. Research Star Trek fonts: Before designing your font, it’s important to familiarize yourself with existing ones. Look at different variations used in TV shows and movies to get an idea of the aesthetic you want to achieve.

2. Sketch out your ideas: Start by sketching out different letterforms and symbols that reflect the essence of Star Trek. Experiment with different shapes, angles, and proportions to find a style that resonates with you.

3. Digitize your sketches: Once you’re happy with your hand-drawn designs, it’s time to digitize them using graphic design software such as Adobe Illustrator or FontForge. Create vector outlines of each character and refine them until they match your vision.

4. Test and refine: After digitizing your designs, testing them in various contexts and sizes is crucial to ensure legibility and consistency. Make any necessary adjustments or refinements until you satisfy with the result.

5. Convert into a usable font file: To use your custom Star Trek font, you’ll need to convert it into a usable font file format such as TrueType or OpenType. There are online tools and software available that can assist with this process.

Remember, designing a font requires patience and attention to detail. Experiment with different styles and iterations until you achieve the desired outcome for your Star Trek-inspired font. May the font be with you.

Copyright And Legal

Being aware of copyright and legal considerations is important when using the Star Trek font. The Star Trek font, or “Starfleet,” is a proprietary font owned by CBS Studios Inc. and can only be used with proper permission or licensing. Unauthorized use of the font can lead to copyright infringement and legal consequences.

If you plan on using the Star Trek font for commercial purposes. It is recommended to seek permission from CBS Studios Inc. or explore licensing options to ensure compliance with copyright laws. It is always best to consult a legal professional for guidance on the appropriate and legal use of copyrighted material like the Star Trek font.

Tips For Using The Star Trek Font Effectively And Legibly

Using the Star Trek font can be a fun and creative way to add a touch of sci-fi to your designs. However, using the font effectively and legibly is important to ensure your message is clear. Here are some tips for using the Star Trek font:

- Choose the right size: Make sure that your font size is large enough to be easily read, especially if you’re using it for headings or titles.

- Use appropriate spacing: Give your text enough breathing room by adjusting the line and letter spacing. This will help improve readability and prevent the text from appearing too crowded.

- Consider contrast: If you’re using the Star Trek font on a background image or pattern, make sure there is enough contrast between the text and the background to be easily readable.

- Keep it simple: Avoid using excessive special effects or decorative elements with the font, as this can make it difficult to read. Stick to clean lines and simple designs to ensure legibility.

By following these tips, you can ensure that your use of the Star Trek font is effective, legible, and adds just the right amount of sci-fi flair to your designs.

The Star Trek font is a unique and recognizable typeface that has become iconic in popular culture. It is instantly associated with the beloved science fiction franchise and holds a special place in the hearts of fans worldwide.

Whether you’re creating fan art, designing a Star Trek-themed website, or simply wanting to add a touch of sci-fi flair to your projects, the Star Trek font will make a bold statement. Embrace the spirit of exploration and adventure with this distinctive typeface, and let your creativity soar among the stars. Live long and prosper.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the star trek font, and what does it look like.

The Star Trek font is a modified typeface of Futura that was first used in the episode “The Naked Time.” People typically use it to represent futuristic technology in the show.

How Did This Font Come About, And How Long Has It Been Around?

The font “Star Trek” was created for the show in the 1957s. However, developers have used it in various movies, books, and other media.

Recently, Star Trek fans have started to resurrect the font’s usage on various online platforms like Tumblr and deviantART.

What Is The Font handy In The Star Trek Wordmark, And Why Is It Good?

The font used in Star Trek’s wordmark is Futura. From books to ads to movies. In 1966, the TV show Star Trek used this typeface as its main wordmark.

What Is The Font Handy In The Star Trek Wordmark?

The font used for the wordmark for Star Trek is called Futura and was created by Lucida Grande. It was originally designed for movie posters and advertisements in the 1960s. But its popularity led to its use on television series like Star Trek and Doctor Who.

How Did The Star Trek Font Come To Be handy In The Show?

The Star Trek font was for a movie poster and later handy in the show. Its creators, Roger Linn and Michael de Castro, wanted to create a typeface that would be “iconic” and reflect the futuristic nature of Star Trek. The font has since been widely popular with both believers and non-believers of the show alike. You may have even seen it on products like T-shirts or stickers in your home.

David Egee, the visionary Founder of FontSaga, is renowned for his font expertise and mentorship in online communities. With over 12 years of formal font review experience and study of 400+ fonts, David blends reviews with educational content and scripting skills. Armed with a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design and a Master’s in Typography and Type Design from California State University, David’s journey from freelance lettering artist to font Specialist and then the FontSaga’s inception reflects his commitment to typography excellence.

In the context of font reviews, David specializes in creative typography for logo design and lettering. He aims to provide a diverse range of content and resources to cater to a broad audience. His passion for typography shines through in every aspect of FontSaga, inspiring creativity and fostering a deeper appreciation for the art of lettering and calligraphy.

Related posts:

- How To Use Font Awesome Icons: A Beginner’s Guide Font Awesome icons are a popular and versatile tool that can add visual interest and functionality to your website or design project. With over 1,500 icons, Font Awesome offers designers and developers a wide range of options. These icons you...

- A Comprehensive Guide To Font In Latex When it comes to typesetting documents, the choice of font can play a significant role in the overall look and feel of the finished product. In LaTeX, there are a variety of fonts to choose from, ranging from classic serif...

- Embed Font CSS: Best Practices For Optimal Web Performance Embedding fonts in design projects is important to ensure your text displays correctly across different devices and platforms. Did you know that the font you choose for your website can impact its overall performance? Embedding fonts using CSS (Cascading Style...

- How To Use Awesome Font PNG For Stunning Designs – A Guide For Beginners In today’s digital era, design is critical in marketing and branding. Every designer continually looks for ways to make their designs unique, eye-catching, and memorable. One tool that can significantly impact your design is how to use awesome font PNG....

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Star Trek fonts

- View history

The following is a list of fonts used in the different Star Trek series categorized by the companies that hold the rights to them.

- 1 Bitstream

- 3 Mark Simonson Studio

- 4 MicroProse

- 6 Further reading

Bitstream [ ]

Horizon font sample

Galaxy font sample

Millennium font sample

Sonic font sample

Swiss 911 Ultra Compressed font sample

There were at least two Li'l Bits packages released by Bitstream , one for Star Trek: The Original Series and a second for fonts from Star Trek: The Next Generation .

Linotype [ ]

Mark simonson studio [ ], microprose [ ].

With the game Star Trek: The Next Generation - Klingon Honor Guard by MicroProse , the company offered a couple of Klingon -like fonts from the game:

Jefferies Extended font sample

The following is a list of fonts that can be used to achieve lettering as used in the series.

Further reading [ ]

- Dave Addey, Typeset in the Future: Typography and Design in Science Fiction Movies . Abrams, 2018, ISBN 978 -1-4197-2714-6, pp. 80-117.

134 episodes

EXT. Space. The Final Frontier. - This show is about writing in Star Trek. We analyze writing style, rewrite old episodes, and sometimes write our own Star Trek stories. Follow us as we dive deep into what makes Trek so great.

Punch It: Writing in Star Trek The Nerd Party

- TV & Film

- 5.0 • 40 Ratings

- JAN 9, 2020

Punch It 134 - Our Last Indulgent J/C Story

What if J/C was canon? In our last episode of Punch It: Writing in Star Trek, we tackle something near and dear to our hearts. Janeway and Chakotay are in love and you can't convince us otherwise. What if those cowards in the writer's room pulled the trigger and made it canon? We make up the relationship on the fly and figure out how the show would change if it was revealed they have been in an intimate relationship. Thank you all for listening.

- DEC 5, 2019

Punch It 133 - Stranded in LA

What if the Voyager crew got stranded in LA when they went back in time? In Star Trek: Voyager's "Future's End" the crew got taken back to 1990s LA. They had to find their way back and of course, they did. But what if they didn't right away? What would happen? Would they get jobs? Would they move on? Would they stay together? We answer these questions and a whole lot more.

- NOV 21, 2019

Punch It 132: Survival Training

22nd Century Short Trek This week we tackle Short Treks once again but this time within the 22nd century. Enterprise showed a great relationship between Trip and Archer. We wanted to expand on that and talk about their survival training together in Death Valley. What type of Enterprise short trek would you guys like to see from Star Trek?

- NOV 14, 2019

Punch It 131: Give Me the Tour

24th Century Short Treks This week we take a fantastic listener suggestion and develop 24th century Short Treks that bridge The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, and Voyager. We took a stab at two and an interesting theme came up that is revealed in the title. What are some Short Trek ideas you would have liked to have seen in the 90s?

- OCT 31, 2019

Punch It 130 - Animating the Future

What stories could be explored if Star Trek leaned heavy on animation? We've had Star Trek: The Animated Series and now we're getting Lower Decks. But what if an executive came into a room and said "We're starting a new initiative with a lot of animated Star Trek projects. Pitch me some ideas." This week, we discuss that scenario and explore what kind of stories could be told.

- OCT 24, 2019

Punch It 129 - Eating Tribbles

Punching Up "The Trouble with Edward" Char didn't like the latest Short Trek and Tristan thought it was fine. Regardless of your opinion on the quality of the episode, there are more than a few things that stand out as puzzling. This week, your Punch It crew takes the episode and figures out how they can punch it up and have it appeal to a wider Star Trek audience.

- © Copyright The Nerd Party

Customer Reviews

Live long and punch it.

Excellent podcast! Tristan and Char have a unique dynamic I’ve loved since TTJ. I enjoyed their episode rewrites before, and now they’ve combined two of my favorite things; writing and pop culture (specifically Star Trek). They do it so well! I have a blast listening to their comments and analysis. Definitely been a morale booster in quarantine. Great job Team Lizard Babies! Much love from a loyal fan 😊

My Favorite Star Trek Podcast.

I like this podcast for the same reason that I love Star Trek in general, and that is the positive attitude with which they deliver thier opinions and writing creations. So many podcasts focus on what they like least about the shows that they are supposedly fans of, but Tristan and Char spend more time dwelling on the aspects of the show that they enjoy and then expound on them in thier writing. Their collaborative writing creations are drafted with respect and kindness for each other, and it is entertaining to listen to the process as it happens. I have listened to them from thier time on To The Journey (and also am a huge J/C shipper), and thier creations just seem to get better and better.

Trek Fiction Writer’s Room?

Tristan and Char are a great team going back to their “To the Journey” days. Their similar thoughts on a lot of matters make this such an entertaining show! Only criticism is that I get so caught up in their stories, I find myself wanting to see the finished product on screen!

Top Podcasts In TV & Film

More by the nerd party.

An archive of Star Trek News

Do You Have What It Takes To Write For Star Trek?

- Self-Reflection : Re-Evaluating your Failures and Successes

Before we talk about agents and publishers, lets go more in-depth about just what type of Trek material will get you noticed in the publishing or television world. Step Two: Finding Your own Voice and Step Three: Selling the Idea will be in the next installment of this five part series.

You may have missed

Several S&S Trek Books On Sale For $1 This Month

- Star Trek: Lower Decks

Another Classic Trek Actor On Lower Decks This Week

Classic Trek Games Now On GOG

- Star Trek: Prodigy

Star Trek: Prodigy Opening Credits Released

ARTS & CULTURE

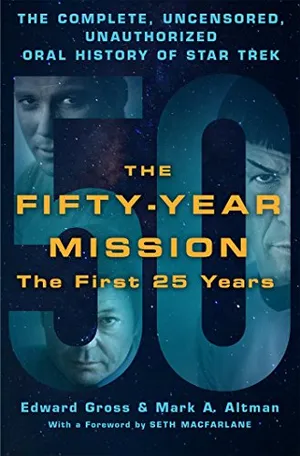

An oral history of “star trek”.

The trail-blazing sci-fi series debuted 50 years ago and has taken countless fans where none had gone before

Interviews by Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/83/8e831889-aaa8-4cda-8509-8ae42407c608/may2016_g01_startrek.jpg)

It was the most wildly successful failure in television history. First shown on NBC 50 years ago this September, the original “Star Trek” lasted just three seasons before it was canceled—only to be resuscitated in syndication and grow into a global entertainment mega-phenomenon. Four live-action TV sequels, with another digital-platform spinoff planned by CBS to launch next year. A dozen movies, beginning with 1979’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture and resuming this July with the director Justin Lin’s Star Trek Beyond . It finds Capt. Kirk (Chris Pine) and Spock (Zachary Quinto) in deep space, where they are attacked by aliens and stranded on a distant planet—a plot that may make some viewers glad that at least the special effects are new. Over the decades “Star Trek” merchandise alone (because who does not need a Dr. McCoy bobblehead?) has reportedly brought in some $5 billion.

This is quite an outpouring for a concept that its creator, the Los Angeles police officer-turned-TV-writer Gene Roddenberry, pitched to producers as a “space western” and once described as a “‘Wagon Train’ to the Stars.” There’s much, much more to the appeal of the original “Star Trek” than gunplay in the wilderness, of course, as countless articles and dissertations have tried to explain, but in one key respect Roddenberry’s notion was right on target: People everywhere, especially Americans, are fascinated by the frontier, whether final or not. And fans are still intrigued that Roddenberry, a World War II veteran, set his 23rd-century multiracial epic in a universe that seemed to be moving beyond bigotry and petty conflict, a cold war-era imagining of the future that was reassuringly counter-dystopian. Plus, you’ve got to love the gadgets—mobile communicators, videoconferencing, diagnostic scanners, talking computers—which have had an uncanny habit of turning up in real life lately, a tribute to the wit and ingenuity of not only Roddenberry but also the show’s designers and writers.

The richness and persistence of the original vision are what make an extensive oral history of “Star Trek” so compelling. (The same cannot be said of “ The Newlywed Game ,” for instance, another TV show that debuted in 1966.)

For more than 30 years, Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman have made it their mission to document the creative process underlying “Star Trek” in all its iterations. In tens of thousands of hours of interviews conducted everywhere from Gene Roddenberry’s Bel Air mansion to movie set camper trailers, the writers recorded virtually anyone who put his or her stamp on this pop culture monument. The result is The Fifty-Year Mission: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Star Trek : The First 25 Years , excerpted here. (Volume 2 is in the works.) “What I loved about the oral history format,” says Altman, “was that it was like getting 500 people in a room and telling the story in a linear fashion.” It was, adds Gross, a “genuine labor of love.”

The Fifty-Year Mission: The First 25 Years

"The Fifty-Year Mission" by Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman. Copyright (c) 2016 by the authors and reprinted by permission of Thomas Dunne Books, an imprint of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

Gene Roddenberry (creator and executive producer, “Star Trek”) I remember myself as an asthmatic child, having great difficulties at 7, 8 and 9 years old, falling totally in love with Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle and dreaming of having his strength to leap into trees and throw mighty lions to the ground.

There was a boy in my class who life had treated badly. He limped, he wheezed. He was a charming, intelligent person. Because of being unable to do many of the things that others were able to do, he had sort of gone into his own world of fantasy and science fiction. He had been collecting the wonderful old Amazing and Astounding magazines, and he introduced me to science fiction. I then discovered in our neighborhood, living above a garage, an ex-con who had come into science fiction when he was in prison. He introduced me to John Carter and those wonderful Burroughs things. By the time I was 12 or 13 I had been very much into the whole science fiction field.

In World War II, Roddenberry served in the U. S. Army Air Corps as a B-17 pilot. He joined the Los Angeles Police Department in 1949, and wrote speeches for Chief William Parker as well as articles for the LAPD newsletter, The Beat. Resigning in 1956, Roddenberry provided scripts to the screenwriter Sam Rolfe, for “Have Gun Will Travel,” the TV western starring Richard Boone. Roddenberry had his first pilot produced by MGM in 1963, for the short-lived NBC series “The Lieutenant.” The studio turned down his pitch for a new series called “Star Trek .” But his agents contacted Desilu Studios, which was looking to produce more dramas after years of success in comedy.

Gene Roddenberry I was tired of writing for shows where there was always a shoot-out in the last act and somebody was killed. “Star Trek” was formulated to change that. I had been a freelance writer for about a dozen years and was chafing at the commercial censorship on television. You really couldn’t talk about anything you cared to talk about. It seemed to me that perhaps if I wanted to talk about sex, religion, politics, make some comments against Vietnam, and so on, that if I had similar situations involving these subjects happening on other planets to little green people, indeed it might get by, and it did.

Dorothy “D.C.” Fontana (writer, “Star Trek” story editor) Gene asked me to read the very first proposal for “Star Trek” in 1964. I said, “I have only one question: Who’s going to play Mr. Spock?” He pushed a picture of Leonard Nimoy across the table.

Gene Roddenberry Leonard Nimoy was the one actor I definitely had in mind—we had worked together previously. I was struck at the time with his high Slavic cheekbones and interesting face, and I said to myself, “If I ever do this science fiction thing, he would make a great alien. And with those cheekbones some sort of pointed ear might go well.” To cast Mr. Spock I made a phone call to Leonard and he came in. That was it.

Leonard Nimoy (actor, “Mr. Spock”) I went in to see Gene at Desilu Studios and he told me that he was preparing a pilot for a science fiction series to be called “Star Trek,” that he had in mind for me to play an alien character. I figured all I had to do was keep my mouth shut and I might end up with a good job here. Gene told me that he was determined to have at least one extraterrestrial prominent on his starship. He’d like to have more, but making human actors into other life-forms was too expensive for television in those days. Pointed ears, skin color, plus some changes in eyebrows and hair style were all he felt he could afford, but he was certain that his Mr. Spock idea, properly handled and properly acted, could establish that we were in the 23rd century and that interplanetary travel was an established fact.

Marc Cushman (author, “ These Are the Voyages ” ) Desilu came into existence because Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz owned “I Love Lucy.” It was the first time someone owned the rerun rights to a show. Seems like a no-brainer today, but back then no one had done it. Eventually CBS bought the rerun rights back from Lucy and Desi for a million dollars, a lot of money back then. Lucy and Desi take that money and buy RKO and turn it into Desilu Studios. The company grows, but then the marriage falls apart and Lucy ends up running the studio and by this point, they don’t have many shows. Lucy says, “We need to get more shows on the air,” and “Star Trek” was the one she took on, because she thought it was different.

Herbert F. Solow (executive in charge of production, “Star Trek”) I had so many people at the studio, so many old-timers trying to talk me out of it. “You’re going to bankrupt us, you can’t do this. NBC doesn’t want us anyway, who cares about guys flying around in outer space?” The optical guy said it was impossible to do.

Marc Cushman Desi wasn’t there anymore. So Lucy is asking herself, “What would Desi do?” because she really loved and respected him. “Desi would get more shows on the air that we own, not just that we’re producing for other companies.” That was her reasoning to do “Star Trek”—and she felt that this show could, if it caught on, rerun for years like “I Love Lucy.” And guess what? Those two shows—“I Love Lucy” and “Star Trek”—are two shows that have been rerunning ever since they originally aired.

In the teleplay for the first pilot, “The Cage,” starring Jeffrey Hunter as Capt. Christopher Pike, Roddenberry described the establishing shot in detail: “Obviously not a primitive ‘rocket ship’ but rather a true space vessel, suggesting unique arrangements and exciting capabilities. As CAMERA ZOOMS IN we first see tiny lettering ‘NCC 1701- U.S.S. ENTERPRISE . ’”

Walter M. “Matt” Jefferies (production designer, “Star Trek”) I had collected a huge amount of design material from NASA and the defense industry which was used as an example of designs to avoid. We pinned all that material up on the wall and said, “That we will not do.” And also everything we could find on “Buck Rogers” and “Flash Gordon” and said, “That we will not do.” Through a process of elimination, we came to the final design of the Enterprise .

Gene Roddenberry I’d been an Army bomber pilot and fascinated by the Navy and particularly the story of the Enterprise , which at Midway really turned the tide in the whole war in our favor. I’d always been proud of that ship and wanted to use the name.

Roddenberry’s attention to detail even extended to the ship’s computer at a time when computers were punch card–operated behemoths that filled entire rooms. In a memo on July 24, 1964, to production designer Pato Guzman, Roddenberry suggested, “More and more I see the need for some sort of interesting electronic computing machine designed into the USS Enterprise , perhaps on the bridge itself. It will be an information device out of which the crew can quickly extract information on the registry of other space vessels, spaceflight plans for other ships, information on individuals and planets and civilizations.”

Gene Roddenberry The ship’s transporters—which let the crew “beam” from place to place—really came out of a production need. I realized with this huge spaceship, I would blow the whole budget of the show just in landing the thing on a planet. And secondly, it would take a long time to get into our stories, so the transporter idea was conceived so we could get our people down to the planet fast and easy, and get our story going by Page 2.

Howard A. Anderson (visual effects artist, “Star Trek”) For the transporter effect, we added another element: a glitter effect in the dematerialization and rematerialization. We used aluminum dust falling through a beam of high-intensity light.

Though the network had warned the studio not to make the pilot too esoteric— “ Be certain there are enough explanations on the planet, the people, their ways and abilities so that even someone who is not a science fiction aficionado can clearly understand and follow the story,” a 1964 memo said—the network wasn’t satisfied. NBC commissioned another pilot—a rare second chance at being picked up for a series.

Gene Roddenberry The reason they turned the pilot down was that it was too cerebral and there wasn’t enough action and adventure. “The Cage” didn’t end with a chase and a right cross to the jaw, the way all manly films were supposed to end. There were no female leads then—women in those days were just set dressing. So, another thing they felt was wrong was that we had Majel as a female second-in-command of the vessel.

Majel Barrett (actress, "Number One,""Nurse Christine Chapel") NBC felt that my position as Number One would have to be cut because no one would believe that a woman could hold the position of second-in-command.

Gene Roddenberry Number One was originally the one with the cold, calculating, computerlike mind. When we had to eliminate a feminine Number One—I was told you could cast a woman in a secretary’s role or that of a housewife, but not in a position of command over men on even a 23rd-century spaceship—I combined the two roles into one. Spock became the second-in-command, still the science officer but also the computerlike, logical mind never displaying emotion.

Leonard Nimoy Vulcan unemotionalism and logic came into being.Gene felt the format badly needed the alien Spock, even if the price was acceptance of 1960s-style sexual inequality.

The network’s objections to Roddenberry’s Spock included taking exception to the character’s pointed ears, perceived as imparting a vaguely sinister Satanic appearance.

Gene Roddenberry The idea of dropping Spock became a major issue. I felt that was the one fight I had to win, so I wouldn’t do the show unless we left him in. They said, “Fine, leave him in, but keep him in the background, will you?” And then when they put out the sales brochure when we eventually went to series, they carefully rounded Spock’s ears and made him look human so he wouldn’t scare off potential advertisers.

Work on the second pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” began in 1965. The show aired on September 22, 1966, and featured William Shatner as Capt. James T. Kirk, replacing actor Jeffrey Hunter.

Gene Roddenberry At that time, TV was full of antiheroes, and I had a feeling that the public likes heroes. People with goals in mind, with honesty and dedication, so I decided to go with the straight heroic roles, and it paid off. My model for Kirk was Horatio Hornblower from the C.S. Forester sea stories. Shatner was open-minded about science fiction, and a marvelous choice.

William Shatner (actor, “James T. Kirk”) I talked to Gene Roddenberry about the objectives we hoped to achieve, and one was serious drama as well as science fiction. I felt confident that “Star Trek” would keep those serious objectives for the most part, and it did.

Scott Mantz (film critic, “Access Hollywood”) I’d follow Kirk in a second. Shatner’s performance as Kirk is the reason I became a “Trek” fan.

Leonard Nimoy Bill Shatner’s broader acting style created a new chemistry between the captain and Spock.

William Shatner Captain Kirk and I melded. It may have been only out of the technical necessity; the thrust of doing a television show every week is such that you can’t hide behind too many disguises. You’re so tired that you can’t stop to try other interpretations of a line, you can only hope that this take is good, because you’ve got five more pages to shoot. You have to rely on the hope that what you’re doing as yourself will be acceptable. Captain Kirk is me. I don’t know about the other way around.

James Doohan (actor, “Montgomery ‘Scotty’ Scott”) [A few days] before they were actually going to shoot the second “Star Trek” pilot, the director, Jim Goldstone, called me and said, “Jimmy, would you come in and do some of your accents for these ‘Star Trek’ people?” I had no idea who they were, but I did that on a Saturday morning. They handed me a piece of paper—there was no part there for an engineer, it was just some lines, but every three lines or so I changed my accent and ended up doing eight or nine accents for that reading. At the end, Gene Roddenberry said, “Which one do you like?” I said, “To me, if you want an engineer, he’d better be a Scotsman,” because those were the only engineers I had read anything about—all the ships they had built and so forth. Gene said, “Well, we rather like that, too.”

George Takei (actor, “Hikaru Sulu”) The first time I talked to Gene about “Star Trek,” it was for the second pilot and it was an exhilarating prospect, because almost every other opportunity was either inconsequential or defamatory, and here was something that was a breakthrough for a Japanese-American actor. Until then any regular series roles for an Asian or an Asian-American character were either servants, buffoons or villains.

Alexander Courage (composer, “Star Trek”) When Lucille Ball bought Desilu, Wilbur Hatch came in as head of music. When “Star Trek” came on the scene, Wilbur suggested me to Roddenberry and I turned out a theme. Roddenberry liked it and that was it. He said, “I don’t want any space music. I want adventure music.”

The second pilot became a monumental achievement: It persuaded NBC to greenlight the series.

Gene Roddenberry The biggest factor in selling the second pilot was that it ended up in a hell of a fistfight with the villain suffering a painful death. Then, once we got “Star Trek” on the air, we began infiltrating a few of our ideas, the ideas the fans have all celebrated.

Robert H. Justman (associate producer, “Star Trek”) On the last day of production when we were a day over, we did two days’ work in one day. That’s the day that Lucy came on the stage, because we were supposed to have an end-of-picture party and we were still shooting, so in between setups she helped Herb Solow and me sweep out the stage. I think she just did that for effect, because she wanted to get the party started.

On March 6, 1966, Roddenberry dispatched a Western Union telegram to Shatner at the Hotel Richmond in Madrid: “Dear Bill. Good news. Official pickup today. Our Five Year Mission. Best Regards, Gene Roddenberry.”

Not long after “Star Trek” was launched, the audience embraced Leonard Nimoy’s Spock, and the stoic Vulcan science officer soon threatened to eclipse Captain Kirk. Nimoy came up with a list of demands that resulted in the possibility that the character would be replaced. In the end, Nimoy’s demands were met, and the scripts began focusing on Kirk and Spock as a team. But the sense of competition continued.

Marc Cushman They almost didn’t have Spock for the second season of “Star Trek.” The fan mail got so intense during the first year, sacks and sacks of mail every day. His agent said, “He’s getting only $1,250 a week and he needs a raise.” But Desilu is losing money on the show and the board of directors was thinking of canceling it, even if NBC wanted to continue, because it was bankrupting the studio. The one that broke the stalemate was the one that didn’t want Spock in the first place: NBC. “You are not doing the show without that guy. Pay him whatever you need to pay him.”

David Gerrold (writer, “The Trouble With Tribbles”) The problems with Shatner and Nimoy really began during the first season when Saturday Review did this article about “Trek” which stated that Spock was much more interesting than Kirk, and that Spock should be captain. Well, nobody was near Shatner for days. He was furious . All of a sudden, the writers are writing all this great stuff for Spock, and Spock, who’s supposed to be a subordinate character, suddenly starts becoming the equal of Kirk.

Ande Richardson (assistant to writer Gene L. Coon) Shatner would take every line that wasn’t nailed down. “This should be the captain’s line!” He was very insecure.

Herbert F. Solow The last thing we wanted was to have the network, the sponsors or the television audience feel that it was not a wonderful, marvelous family on “Star Trek.” We didn’t want anybody to see a crack in this dam that we built.

If push came to shove, and we had to recast both characters, it would have been easier to recast Bill’s part than Leonard’s, so you tell me: Who’s the star of the show?

William Shatner Occasionally, I’ll hear something from an ardent fan of mine who’ll say, “So and so said this about you.” And it bewilders me because I have had no trouble with them. We have done our job and gone on and I have never had bad words with anyone.

On August 17, 1967, Roddenberry addressed an ultimatum to Shatner and Nimoy, with DeForest Kelley (Dr. McCoy) thrown in for good measure:

“Toss these pages in the air if you like, stomp off and be angry, it doesn’t mean that much since you’ve driven me to the edge of not giving a damn,” Roddenberry wrote in that letter, excerpted here for the first time: “No, William, I’m not really writing this to Leonard and just including you as a matter of psychology. I’m talking to you directly and with an angry honesty you haven’t heard before. And Leonard, you’d be very wrong if you think I’m really teeing off at Shatner and only pretending to include you. The same letter to both; you’ve pretty well divided up the market on selfishness and egocentricity.

“ Star Trek began as one of the TV productions in town where actors, as fellow professionals, were not only listened to but actually invited to bring their script and series comments to the production office. When small problems and pettiness begins to happen as it happens on all shows, I instructed our people that it should be overlooked where possible because we should all understand the enormous physical and emotional task of your job .... The result of Gene Roddenberry’s policy of happy partnership? Star Trek is going down the drain.

“. . . I want you to realize fully where your fight for absolute screen dominance is taking you. It’s already affecting the image of Captain Kirk on the screen. We’re heading for an arrogant, loud, half-assed Queeg character who is so blatantly insecure upon that screen that he can’t afford to let anyone else have an idea, give an order, or solve a problem. You can’t hide things like that from an audience.

“And now, Leonard. I must say that if I were Shatner, I’d be nervous and edgy about you by now, too. For a man who makes no secret of his own sensitivity, you show a strange lack of understanding of it in your fellow actors.

“For as long as I stay with the show, starting Monday,” Roddenberry decreed, “there will be no more line switches from one to anothe r . No more of the long discussions about scenes which lose us approximately a half day of production a show—the director will permit it only when there is a valid dramatic story or interpretation point at stake which he believes makes it necessary. The director will be told he is also replaceable and failure to stay on top and in charge of the set will be grounds for his dismissal.

“All right, my three former friends and ‘unique professionals,’ that’s it. In straight talk.”

David Gerrold All the episodes hold together because Shatner holds it together. Spock is only good when he has someone to play off of. Spock working with Kirk has the magic and it plays very well, and people give all of the credit to Nimoy, not to Shatner.

Leonard Nimoy During the series we had a failure—I experienced it as a failure—in an episode called “The Galileo Seven.” The Spock character had been so successful that somebody said, “Let’s do a show where Spock takes command of a vessel.” We had this shuttlecraft mission where Spock was in charge. I really appreciated the loss of the Kirk character for me to play against. The Bill Shatner Kirk performance was the energetic, driving performance, and Spock could kind of slipstream along and offer advice, give another point of view. Put into the position of being the driving force, the central character, was very tough for me.

Thomas Doherty (professor of American studies, Brandeis University) At the core of “Star Trek” is something profound, which is teamwork and adventure and tolerance. That’s why it’s a World War II motif in the space age. It really is a team; you’re making a heroic contribution by doing your bit.

At the beginning of the second season, several changes greeted viewers. Not only was DeForest Kelley’s name now added to the opening credits, there was a new face at the helm: Navigator Pavel Andreievich Chekov, played by Walter Koenig.

Gene Roddenberry The Russians were responsible for the Chekov character. They put in Pravda that, “Ah, the ugly Americans are at it again. They do a space show, and they forget to include the people who were in space first.” And I said, “My God, they’re right.”

Walter Koenig (actor, “Pavel Chekov”) They were looking for someone who would appeal to the bubblegum set. All that stuff about Pravda , that’s all nonsense. That was all just publicity. They wanted somebody who would appeal to 8- to 14-year-olds and the decision was to make him Russian. My fan mail came from 8- to 14-year-olds who weren’t that aware of the cold war. Getting fan mail was so novel to me that I read every single letter I got. I was getting about 700 letters a week.

Robert H. Justman We had another problem in the second season. We were cut down on how much we could spend per show by a sizable amount of money.

Marc Cushman Lucille Ball lost her studio because of “Star Trek.” She had gambled on the show, and you can read the memos where her board of directors is saying, “Don’t do this show, it’s going to kill us.” But she believed in it. She moved forward with it, and during the second season she had to sell Desilu to Paramount Pictures. Lucille Ball gave up the studio that she and her husband built, it’s all she had left of her marriage, and she sacrificed that for “Star Trek.”

Ralph Senensky (director, “Metamorphosis”) Desilu was like a family. Herb Solow [the production head] used to come down and talk with you on the soundstage. Herb went out of his way to help you. Can you imagine a studio working like that? When Paramount bought it, a kind of corporate mentality took over. That’s why I resent Paramount having such a hit in “Star Trek.” If they had their way, they would have killed it off. It survived in spite of them. Now they have this bonanza making them all of this money.

Marc Cushman Lucy’s instincts were right about “Star Trek,” that it would become one of the biggest shows in syndication ever. The problem was that her pockets weren’t deep enough. They were losing $15,000 an episode, which would be like $500,000 per episode today. You know, if she could have hung on just six months longer, it would have worked out, because by the end of the second season, once they had enough episodes, “ Star Trek” was playing in, I believe, 60 different countries around the world. And all of that money is flowing in.

She had no choice but to sell. She actually took off and went to Miami. She ran away because it was so heartbreaking to sign the contract. They had to track her down to get her to do it. There’s a picture of her cutting the ribbon after they’ve torn down the wall between Paramount and Desilu, and she’s standing next to the CEO of Gulf and Western, which owns both studios now, and she’s trying to fake this smile for the camera, and you know it’s just killing her.

Among the now-classic episodes in Season 2 of the original are “Amok Time,” in which Spock is driven to return to Vulcan to mate or die and finds himself in a battle to the death with Kirk.

Joseph Pevney (director, “Amok Time”) What made the fight in “Amok Time” dramatically interesting is that it took place between Kirk and Spock. During this episode, Leonard Nimoy and I also worked out the Vulcan salute and the statement “live long and prosper” together.

Gene Roddenberry Leonard Nimoycame into my office and said, “I feel the need for a Vulcan salutation, Gene,” and he showed it to me. Then he told me a story about when he was a kid in synagogue. The rabbis said, “Don’t look or you’ll be struck dead or blind,” but Leonard looked and, of course, the rabbis were making that Vulcan sign. The idea of my Southern kinfolk walking around giving each other a Jewish blessing so pleased me that I said, “Go!”

Joseph Pevney “The Trouble With Tribbles” was a delightful show. I had a lot of fun with it, went out and shopped for the tribbles. My biggest contribution was getting the show produced, because there was a feeling that we had no business doing an outright comedy. Bill Shatner had the opportunity to do the little comic bits he loves.

Season 2 also featured visits to a number of Earthlike planets, including one where the society mirrored the Roman Empire.

Ralph Senensky Gene Roddenberry is a very creative man. When we did “Bread and Circuses,” we were doing the Roman arena in modern times with television. We didn’t want to tip that we were doing a Christ story from the word go. Originally when they were talking about the sun, you knew right away that they were talking about the son of God.

Dorothy “D.C.” Fontana Certainly there was a nice philosophy going on there with the worshiping of the “sun,” and then the indication that it was the son of God, that Jesus or the concept had appeared on other planets.

The series was not a ratings powerhouse. Indeed, it seemed that Season 2 could very well be the show’s last. The future was in the hands of the fans.

Bjo & John Trimble (longtime fans) Cancellation was certain at the end of the second season. We wrote up a preliminary letter, ran it off on our ancient little mimeograph machine, and mailed it out to about 150 science fiction fans. We didn’t have enough money to have a letter printed, so we used the Rule of Ten: Ask ten people to write a letter and they ask ten people to write a letter, and each of those ten asks ten people to write a letter.

NBC was convinced that “Star Trek” was watched only by drooling idiot 12-year-olds. They managed to ignore the fact that people such as Isaac Asimov and a multitude of other intellectuals enjoyed the show. So, of course, the suits were always looking for reasons to cancel shows they didn’t trust to be a raging success.

Elyse Rosenstein (early organizer of “Star Trek” conventions) Do you realize how many pieces of mail NBC eventually received on “Star Trek”? They usually got about 50,000 for the year on everything, but the “Star Trek” campaign generated one million letters. They were handling the mail with shovels—they didn’t know what to do with it. So they made an unprecedented on-air announcement that they were not canceling the show and that it would be back in the fall.

Gene Roddenberry The letter-writing campaign surprised me. What particularly gratified me was not the fact that there was a large number of people who did that, but I got to meet and know “Star Trek” fans, and they range from children to presidents of universities.

John Meredyth Lucas (producer; writer, “Patterns of Force”) Some of the most fanatic support came from Caltech.

Gene Roddenberry We won the fight when the show got picked up for a third season. NBC was certain I was behind every fan, paying them off. And they finally called me up and said, “Listen, we know you’re behind it.” And I said, “That’s very flattering, because if I could start demonstrations around the country from this desk, I’d get the hell out of science fiction and into politics.”

“Star Trek” concluded its second season on a high note, with NBC essentially acknowledging the success of the fans’ letter-writing campaign by announcing that the series would be returning.

Gene Roddenberry I told NBC that if they would put us on the air as they were promising—on a weeknight at a decent time slot, 7:30 or 8 o’clock—I would commit myself to produce “Star Trek” for the third year. Personally produce the show as I had done at the beginning. About ten days or two weeks later, I received a phone call at breakfast, and the network executive said, “Hello, Gene, baby . . .” I knew I was in trouble right then. He said, “We have had a group of statistical experts researching your audience, and we don’t want you on a weeknight at an early time. We have picked the best youth spot that there is. All our research confirms this and it’s great for the kids and that time is 10 o’clock on Friday nights.” I said, “No doubt this is why you had the great kiddie show ‘The Bell Telephone Hour’ on there last year.” As a result, the only gun I then had was to stand by my original commitment, that I would not personally produce the show unless they returned us to the weeknight time they promised.

David Gerrold Roddenberry, rather than try and do the very best show possible, walked away and picked Fred Freiberger [as the producer]. I wish Roddenberry had been there in the third season to take care of his baby.

Marc Cushman NBC didn’t like Gene Roddenberry, and they didn’t like the type of shows that “Star Trek” was airing. It was too controversial and too sexy, and they couldn’t get Roddenberry to tone it down. So they move it to Friday night—they didn’t even want to pick it up, but there was the letter-writing campaign that made them cry uncle. They put it in the death slot. And they knew when they picked it up that they were determined that Season 3 would be the last year.

Robert H. Justman If your audience is high-school kids and college-age people and young married people, they’re not home Friday nights. They’re out, and the old folks weren’t watching. So our audience was gone.

Margaret Armen (writer, “The Paradise Syndrome”) Working with Gene was marvelous, because he was “Star Trek” and he related to the writers. Fred came in and to him “Star Trek” was “tits in space.” And that’s a direct quote. Fred had been signed to produce and was being briefed. He watched an episode with me, smoking a big cigar, and said, “Oh, I get it. Tits in space.” You can imagine how a real “Star Trek” buff like myself reacted to that .

Fred Freiberger (producer, “Star Trek,” Season 3) Our problem was to broaden the viewer base. To do a science fiction show, but get enough additional viewers to keep the series on the air. I tried to do stories that had a more conventional story line within the science fiction frame.

Marc Cushman You had some of the most talented people from “ Star Trek” that were leaving. You didn’t have Gene Coon, Gene Roddenberry or Dorothy Fontana finessing the scripts. It’s like having the Beatles and taking away John Lennon and Paul McCartney. “OK, we still have George and Ringo. We’re still the Beatles.” No, you’re not. You’re still good, but not as good.

James Doohan Fred Freiberger had no inventiveness in him at all. Paramount bought Desilu and here was this damn space show as part of the package and they couldn’t care less about it.

William Shatner There was a feeling that a number of Fred Freiberger’s shows weren’t as good as the first and second season, and maybe that’s true. But he did have some wonderfully brilliant shows and his contribution has never been acknowledged.

Bjo & John Trimble The third season ground down, show after show being worse than the last, until even the authors of the scripts were having their names removed or using pseudonyms. To be fair, there were a few good scripts in the third season, but in the main those few seemed to be almost mistakes that slipped by.

While the third year of “ Star Trek” has largely been dismissed as a creative failure, several notable episodes were produced. “Spectre of the Gun” is a surrealistic western in which Kirk, Spock and McCoy find themselves reliving the shootout at the O.K. Corral. “Day of the Dove” focuses on an energy force that feeds on hatred. In “Plato’s Stepchildren,” aliens with telekinetic abilities torture Enterprise crewmen for their amusement—and Kirk and Uhura share television’s first interracial kiss.

Bjo & John Trimble The last third-season episode, “Turnabout Intruder,” was very good; it might have won an Emmy for William Shatner. But all TV shows got rescheduled for President Eisenhower’s funeral coverage. So the episode missed the Emmy-nomination deadline.

Scott Mantz That’s how production ended. There is something somewhat apropos about the last words of the last episode, “Turnabout Intruder”: “Her life could have been as rich as any woman’s. If only...If only.” And then Kirk walks off.

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman | READ MORE

Both considered "Treksperts" with years of experience writing about Star Trek, Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman are the authors of The Fifty-Year Mission: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Star Trek: The First 25 Years .

OngoingWorlds blog

By David Ball

12 tips for writing Star Trek fanfiction & roleplaying

Category: Character Development , Inspiration for writing , Writing tips Tags: Fanfiction , star trek 2 Comments

Star Trek fanfiction is as old as Star Trek itself, and heavily dominates the world of online roleplaying. There’s many giant Star Trek roleplay clubs, like Starbase 118 and Star Trek: Borderlands . We’ve even got Star Trek games running on OngoingWorlds ( see here ). Here’s some tips for anyone who wants to write fiction in the Star Trek universe:

Don’t stereotype the races

SEE ALSO: Infinite diversity in… you know the rest, right?

Star Trek has many great alien species to choose from, each with their own traits. Klingons like fighting, Romulans are sneaky, Ferengi are out for a profit. But your characters don’t have to follow these traits exactly. People are individuals, and not everyone from a planet is exactly the same. Not all science officers have to be Vulcan, not all Tactical officers have to be Klingon. Mix it up a little bit!

There’s an entire universe out there

Even though Star Trek does have some great alien races, it’s also a show about exploration and discovering the unknown. Invent a new type of species every now and again that your characters meet. Your main characters can also be new and different types of aliens that you’ve made up, which is a great way to explore an interesting new type of species.

Also don’t be afraid of playing a Human character. Even though there’s a lot of exciting aliens, Humans are pretty special too .

Avoid too much technobabble

Actually it’s not the technobabble that’s the problem, it’s overly-complicated situations based on a scientific theory that make your story waaay too difficult to understand, and too complicated for your other players to keep up with. Keep your plots simple, running with one out-there theory at a time, so it doesn’t get too insane.

Do your research

A series as long-running as Star Trek gives you a lot of starting material, but make sure you’re not writing anything that contradicts something that’s already canon. That being said, don’t let canon handcuff you, there’s plenty of exceptions to any rule made up by the show if you give a good explanation.

Avoid characters that are related to characters we know

It might seem a good way to legitimize your character by relating them to an existing character, like Kirk’s cousin, or Picard’s long-lost nephew. But it can also be tacky, especially if everyone does it. Also, remember the point above about doing your research , Picard’s only nephew died.

Give your characters goals

SEE ALSO: Characters who give you quests

This isn’t related specifically to Star Trek fanfiction or roleplay, it’s just good advice. Make sure your characters are well-rounded and have goals, and ways of achieving those goals ( more about character goals here ).

Go easy on the hybrids

Many people like to make their characters a hybrid of different races. Spock was half-human, half Vulcan, so this is in Star Trek’s very nature to explore this concept of a character being from two worlds, but never really fitting into either. But I’ve seen people make characters with such a mixed and complicated heritage that it becomes ridiculous. If you want to write about a Hybrid, it’s probably best to keep it simple and leave their grandparents out of it. The galaxy isn’t ready for a Trill-Klingon-Bajoran-Cardassian yet.

Also think about whether the species can actually breed first, as aliens might have very different mating and birthing practices. For example you’d better have a very good explanation of how a Vulcan/Tribble hybrid even happened!

Avoid Q-like characters

We’ve got many articles about why an all powerful character is a bad idea. Here’s a list:

- All-powerful characters are boring

- Godmodding: The Q effect

- What is godmodding and why is it annoying?

Use the vastness of space to your advantage

Space is BIG. And you can use this to your advantage in certain situations. Star Trek is mostly about exploration so you’ll probably have situation where your crew are out on the frontier and unable to call Starfleet Command for advice or backup. This means the tough decisions will be forced upon your Captain and crew, who will have to stand by any decision they make.

Put realistic limits on sensing devices

The idea that a character can look at his magic sensor display or tricorder and learn everything about a situation, down to the DNA of the aliens aboard an approaching ship that’s thousands of miles away, has robbed many a Star Trek story of the mystery and danger of space exploration from which the franchise theoretically derives much of its appeal. Don’t let this happen to you. So what if it happened on Enterprise or Voyager? Don’t let yourself be bound by other people’s lazy writing choices. And don’t feel obliged to “explain” via technobabble infodump why your ship’s sensors can’t instantly tell what color underwear the people on an approaching vessel are wearing. Figure out the parameters in your head and then simply have the story abide by them without overexplaining.

Use parallel universes/time-travel/cloning etc to your advantage, but don’t overdo it

There’s a lot of scifi concepts in Star Trek that you can use to create fantastical adventures, but don’t rely on this every single time or it’ll soon get boring.

Don’t get caught up in the technicalities

Star Trek is a geek’s dream because of all the exciting technology and gadgets, but it’s important not to get bogged down in all of this. At it’s core, Star Trek is a show about people. Gene Roddenberry’s original pitch heavily stressed this , which is why you should continue this in your own fanfiction.

Technology like tricorders, ship’s scanners and phasers are useful tools, but your characters still need to make the important decisions to get them out of a scrape.

Some of the tips were inspired by comments from this comment thread on Trekbbs.com .

Play-by-post Games

Recent posts.

- Spelling Tips: Part IV

- 2022 Simulation Cup Results… Finally!

- Top Blog Posts of 2023

- SciWorld 21 is coming!

Subscribe via Email

Email Address

Random Posts

- Roleplayers: We’re definitely not antisocial subterranean morlocks

- What's your RP doing for Christmas?

- The other Simming Prize winners… including The Gamemaster!

- Flashback week roundup

- Monthly game summaries

Like this? Become a Patreon!

- Show Spoilers

- Night Vision

- Sticky Header

- Highlight Links

Follow TV Tropes

http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/SignatureStyle/Literature

Signature Style / Literature

Edit locked.

- David Foster Wallace : juxtaposition of informal abbreviations and slang with incredibly esoteric words , words which originally seem incredibly esoteric but end up being made up (usually somehow derived from Latin), the odd continued use of &c. instead of etc. (again with the esoteric Latin thing), compulsive use of footnotes (sometimes useless footnotes, sometimes carrying out entire storylines within footnotes), scenes which are both hilarious and heartbreaking (or disturbing but usually both), obscure connections which are absurd and profound and also pretty funny, &c. And the word "peripatetic," which he seemed to like as much as this wiki likes the word egregious .

- J. K. Rowling seems to like every trope related to Chekhov's Gun . If a character, object, or place is mentioned in passing in an early books, it's almost guaranteed to show up later, usually in a role of vital importance. She also seems to like killing off characters just to show that death is harsh. She also seems fond of semicolons. Stephen King once commented snarkily that she "never met an adverb she didn't like."

- He's quite fond of incredibly drawn-out, horrible puns (for example, in Sir Apropos of Nothing , taking a full page to explain why a group of crazy bird-men descended from harpies are called the Harpers Bizarre) and Ironic Echo Cut chapter breaks. He's also very fond of the adverb "nattily": if his work is set in modern times, expect everybody to be "nattily dressed."

- David also enjoys the Running Gag . One notable example from one of his Star Trek novels had a Vulcan character simply trying to go from one part of the ship to another and constantly running into a string of people, from fellow crewmembers to an alien ambassador, who all insisted on telling her their current personal problems. She finally blows a gasket and demands to know why everyone was telling her . (Well, the closest to gasket-blowing a Vulcan usually gets, anyway.)

- Another aspect of his Star Trek writing is a very thorough knowledge of the show, with in-jokes, Shout Outs , and obscure references everywhere. This is epitomized in Morgan Primus , who is, effectively, Majel Barrett Roddenberry. Primus has been mistaken for, compared to, or otherwise tied to each of the characters Majel has played in the Trek universe: Number One in the original pilot, Nurse Chapel, Lwaxana Troi...and so on. She eventually has her mind downloaded into the ship's computer. It takes a while for the crew to realize it, though, because guess who voices Federation computers on the show?

- He also seems to be able to work in a throwaway reference to Alexander the Great somewhere in many things he's written.

- Robert Rankin's style makes it obvious that he's making it up as he goes along , as he lampshades in one book, pointing out plot threads that don't go anywhere. Sometimes it works, and sometimes... it just doesn't.

- Tom Holt has incredible fun with metaphors, cliches and truisms; if the book is full of metaphors taken to extremes, it's probably him. He also tends to feature mopey, nerdy males and rock-hard, super-efficient females. His stories also have an extremely cynical view of love, which is often portrayed as more of a nuisance or a disease than anything actually good .

- He's fond of irony, wordplay, humorous similes and puns.

- He likes justifying the natural laws of his worlds as being governed by tropes and clichés , which people can use to their own advantage if they're Genre Savvy enough. The fact that his characters can usually predict what happens later in the story via recognition of tropes and cliches actually makes the stories less predictable .

- His books also very rarely use conventional chapters.

- His earlier works in particular like to play with the idea of unearthly eyes, and particularly the idea that the eyes are the only thing that no magic can disguise, providing a window to the true nature of the soul.

- He is also well-known for his use of comedic footnotes , even requiring a Footnote character in the play version of some books, and one of his compilation books is titled Once More* With Footnotes . And he seems to love the words 'strata' and 'apologetic'.

- Pratchett is inordinately fond of characters who immediately try to describe why a certain thing is funny before other characters could even react to the joke.

- He also loves Painting the Medium by using different font sizes, types, or capitalisation, to render the speech of unusual entities. Many of his characters with otherwise normal speech patterns are also noted as being somehow able to pronounce font types or punctuation.

- His female characters are usually very strong-willed, independent, and more than a little snarky.

- A recurring theme, particularly in his Young Adult novels, is a character or group of characters discovering that the world is much larger or complex than they thought at first, and vastly broadening their mind as they come to terms with how limited their view originally was.

- His main characters are often particularly skilled in their line of work, or exceptionally gifted in a specific area.

- He has a great love of wordplay and cliche. His Xanth series, in particular, is one great big Hurricane of Puns after another, but his other works can be similarly blunt and heavy-handed at times.

- He makes nearly every protagonist a moral paragon who never does anything wrong and never fails at anything.

- Another reoccurring theme in Anthony's works is nudity and sexuality, even in his young adult / teen series, Xanth . Anthony is pretty frank about his beliefs — he doesn't believe human nudity is harmful or shameful at all, and he remembers that most of the people of his target audience's age are actually quite curious about sexuality, despite what their parents may think. His works are never outright pornographic, but it skirts the boundaries enough (mermaids turning into humans and not knowing about clothes, princesses having to trade their clothes for a magic sword, that kind of thing) that he's been accused of being a pedophile on several occasions.

- And also the use of children/extended family of characters he's already used, to the point where the Royal Family of Xanth is on something like its fourth generation.

- He likes the words "demesnes" and "proffer."

- Especially prevalent in the early Xanth novels is the use of the dialogue tag "...he/she cried."

- Douglas Adams always has a narrator that goes off into tangents, Insane Troll Logic actually working and Contrived Coincidences . And Lampshading the ridiculousness of it all. His heroes are an Unfazed Everyman or a hypersavvy slacker. His works tend to have a lot of absurd humor that often correspond satirically with modern culture.

- Another Mercedes Lackey signature: taking a character who has grown up living in serious misery without family, usually without real pleasures or more than one or two friends, then having them get swept up, as in a Changeling Fantasy , and taken to somewhere with good people and comforts, where there is hard work and good food. Said character never brings along the optional friend, nor do they ever go back, and they always turn into Standard Lackey Hero characters, who are all uniform in their goodness. There is a long period of adjustment where the character makes friends, and towards the very end there is a rushed conclusion. Seriously, this happens in very nearly every book, more often now than in her earlier work. It's alleviated significantly when she collaborates with different authors, though the book she wrote with Piers Anthony was cringe-worthy.

- A key Lackey trademark is her standard protagonist development sequence, which has been summarized as "make the readers love and adore the hero, and then tear said hero's arms off."

- Also, all of her villains are rapists or otherwise sexually deviant. All of them . Van Rothbart, from the Black Swan, is never described or depicted as raping, molesting, or otherwise sexually harming anyone. But he does VERY MUCH seem to enjoy controlling and punishing women, especially strong-willed ones.

- Neal Stephenson 's main characters are always incredibly smart, with a breadth of technical and practical knowledge. Often their friends are even more brilliant. The narrative will include meticulous analysis of wide range of subjects that Stephenson finds interesting, from the outright arcane to the humorously mundane. Some of these factor into the plot, and others are simple digressions. The writing style features quite a lot of dry humor, including the pet phrase: "X would like nothing more than Y. Which is too bad, considering he's Z right now." His novels, especially his early ones, are also notorious for having unsatisfyingly abrupt endings.

- H. P. Lovecraft writes with Sesquipedalian Loquaciousness . Most of his stories are horror stories about eldritch abominations that humanity cannot fathom . Women don't come off very well in his stories, and overtly racist themes against dark-skinned people are common. Cats, however, are always treated with respect. Lovecraft also loved his home town of Providence. His plots often placed The Reveal at the end of the story. Often the climax would be the character discovering The Reveal, and at the end they would recall/ponder it for the reader. Also, his stories are almost always narrated in first person by male characters, and are often precisely dated. His stories are often written as if they are journals or reports written by the narrator, sometimes because he can no longer stay silent about the things he has witnessed.

- Edgar Allan Poe also used Antiquated Linguistics , and if he wasn't writing a C. Auguste Dupin story, he usually featured a skeptical and normally problematic narrator that tried to face the supernatural reasonably, but ended engulfed by madness. His stories generally ended in a very abrupt, anti-climactic way. And there'd be a beautiful woman who had died or is dying.

- He seems to love Wacky Wayside Tribes , rhyming prophecies , intense description of food, and making damn sure none of his heroes ever die. This last element has only slid in over time; while the earlier Redwall books were willing to let heroes die ( Martin the Warrior and Outcast of Redwall most notably), the later ones have the "hero shield" at full power.

- This doesn't apply in Castaways of the Flying Dutchman , which hasn't suffered the Redwall series's cumulative decay: the fisherman in the first book, the French captain in the second book, and Serafina in the third book all died rather horribly .

- He also has a thing for giving characters names beginning with the letter M.

- He is quite heavy on the Black And White morality (the number of ambiguous characters being counted on one hand), with tons of Always Chaotic Evil and Always Lawful Good Funny Animal species in the Redwall series.

- Redwall features copious Food Porn in each book.

- He also likes references to classic rock and folk music and to classic fantasy and science fiction, love triangles where the main man does not get the girl, manipulators that make other parties fight each other while staying out of the conflict themselves, and protagonists that are broken or different in some way.

- R.A. Salvatore has described his combat scenes as "Crouching Panther, Hidden Dark Elf". They would not look out of place in anime or a Hong Kong martial arts flick. Including the over-the-top-ness.

- He's known for frequent use of a distinctive ( Stream Of Consciousness ) writing style which incorporates the character's thoughts into a paragraph, typically ( through parenthetical insertion) breaking the standard paragraph structure as he goes along.

- When he wrote using the pseudonym Richard Bachman, people suspected it was him based on his style.

- The endless describing of daily life inconsequentia. This even extends to simple actions the character performs. For instance, when a character kneels down, King will often point out that the character's knees cracked like gunshots as he did so.

- He also tends to write stories featuring protagonists with similar characteristics to himself. In his early career, he often wrote about lower-class teachers. After his rise to success and car accident, his heroes often had great wealth, were a writer, and/or suffered a horrific injury with an agonizing recovery.

- If the book is taking place in one of his many small towns in Maine, he has to have at least one chapter where he takes the reader out of the main narrative, and on a bird's eye trip around town to see what the minor characters are getting up to.

- His characters tend to have very detailed back stories, which either fit (directly or indirectly) into the main plot of the book, or provide the characters with metaphors/stock phrases that will be used frequently when they're the viewpoint character. He also likes to tell you that a just-introduced character is about to die, and then give you the character's back story.

- He likes using animals as viewpoint characters.

- King also likes mentioning brand names often, not just genericized trademarks like "Kleenex" or "Aspirin" . It gets to the point the reader might wonder if this is Product Placement . Brand names show up more often in his novels than his short stories.

- Michael Moorcock loves the initials J.C. . He did this quite deliberately, to show that they represented aspects of the same archetype.

- Similarly, Philip José Farmer used the initial PJF to refer to his stand-ins , according to him. Given one was a sci-fi author who was defrauded by a publisher this clue was perhaps overkill.