Biography Online

Lao Tzu Biography

Life of Lao Tzu

Amongst historians there is uncertainty over the historical facts about Lao Tzu’s life – some even doubt whether he existed. But, the most prominent sources suggest he was born with the birth name of Er Li in the 5th or 6th Century BC. Laozi 老 was an honorific name which means “Old venerable, Master” It can be anglicised in different ways – hence both Laozi and Lao Tzu have been used.

The strongest historical sources suggest he worked as a scholar and served as the keeper of the archives for the Royal Court of Zhou. Lao Tzu would have had access to the great literature of ancient Chinese culture and this would have informed his own philosophy. However, Lao Tzu went beyond synthesis of past ideas and created a new strain of philosophy – which expressed mystical sentiments in thought-provoking paradox and analogies.

“Knowing others is intelligence; knowing yourself is true wisdom. Mastering others is strength; mastering yourself is true power.”

Tao Te Ching . Ch. 33, translated by Stephen Mitchell (1992)

The philosophy and teachings of Lao Tzu are said to have drawn many students and disciples who began following him. However, there are no records of Lao Tzu creating a formal school.

The essence of Lao Tzu’s teachings was the importance of seeking to live in harmony with the Tao. Lao Tzu implied that the Tao was beyond name and form and could never adequately expressed in words.

“The Tao that can be expressed is not the eternal Tao; The name that can be defined is not the unchanging name.”

Tao Te Ching

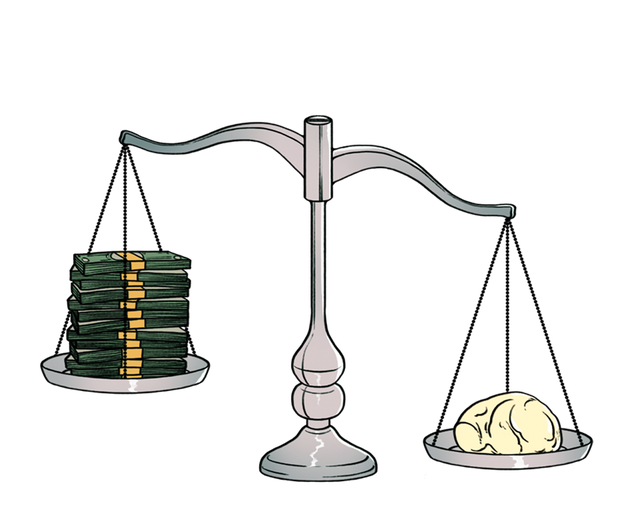

The Tao Te Ching gives advice for a seeker to go beyond the limited ego, and gain a greater appreciation for the invisible power and force which underlies the universe. The Tao Te Ching is a classic of mystical philosophy. It challenges conventional wisdom and the earthly pursuit of wealth, power and success. By contrast, it encourages the qualities of humility, modesty and simplicity.

“Wise men don’t need to prove their point; men who need to prove their point aren’t wise. The Master has no possessions. The more he does for others, the happier he is. The more he gives to others, the wealthier he is.”

It suggests the best form of leadership is to lead from behind, not grasping for power, but using gentle methods of persuasion to keep people on the right track.

“The Tao nourishes by not forcing. By not dominating, the Master leads.”

According to the Tao Te Ching, the ultimate goal of life is to attain the state of wu wei – free from desires. This can be achieved by emptying the mind and going beyond awareness of the body and human ego.

The Tao Te Ching is not for a mere literal understanding. When it talks about the virtue of ignorance, Taoist scholars suggest this means the absence of worldly vanity and false pride in material knowledge. The Tao also avoids the fundamentalism of religious texts. It doesn’t list a set of commandments, but suggests the Tao is a guide with no fixed path – each individual must follow the Tao according to his inner prompting.

“The Tao is teachable, yet understanding my words is not the same as following the Tao. The guidance is describable, yet knowing the description is not the same as following the guidance.”

In the Zhuangzi , the author relates a meeting between Lao Tzu and Confucius . Confucius was an eminent scholar and philosopher in his own right. Confucius promoted a more formal philosophy which emphasised formality and deference to your elders. Lao Tzu took a more intuitive and liberal approach, which emphasised the importance of being in tune with the universal harmony – and not just the conventions of the time. However, the meeting suggested a mutual appreciation for their respective approaches. The three philosophers Master Zhuang, Confucius and Lao Tzu, are the most notable Chinese philosophers. The Zhuangzi and the Tao Te Ching are the two cornerstones of Taoism.

In one version of Lao Tzu’s life, he married and had a son called Zong who became separated from him and went on to be a celebrated soldier. At a later time, Lao Tzu comes across a great military figure who is celebrating a military victory. It is at this point that Zong recognises his long-lost father. Lao Tzu then gives advice to his son – in particular, the value of respecting the defeated army and giving his foes a proper burial. Through listening to his father and avoiding a sense of triumphalism, Zong was able to broker a peace between the warring parties which lasted for many years.

In another version of Lao Tzu’s life, based on the writings of Sima Qian (a Chinese Historian of the early Han dynasty 206 BBC) Lao Tzu lived in Changzhou. However, he became discouraged by the moral decay and worldliness of the city. Seeking peace to meditate, he resolved to leave the city and live as a hermit in the mountains. However, at the western gate of the city, he was stopped by a guard Yinxi, who asked Lao Tzu to write his knowledge down for the benefit of citizens before he was given a pass to leave. It was at this juncture that Lao Tzu wrote the Tao Te Ching. In some versions of the story, Yinxi was so impressed with Lao Tzu that he became his disciple and followed Lao Tzu into exile. Yinxi then followed the different Taoist disciples of preparation and obedience to his Master – after completing a long period of preparation and training. He became the model Taoist student.

Religious interpretations of Lao Tzu

Lao Tzu is generally regarded as the founder of Taoism. In some branches of Taoism, Lao Tzu is worshipped as a God. Lao Tzu was viewed as a perfect personification of the Tao and throughout history, he has appeared to lead humanity towards its goal.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “Biography of Lao Tzu”, Oxford, UK – www.biographyonline.net . Published 27 January 2019. Last updated 27 Jan 2019.

Pythagoras: His Life and Teachings

Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu at Amazon.com

Chasing the Pearl of Lao Tzu

A tale of ancient philosophers, alien abductions, murder-for-hire—and how the world’s largest pearl came to be the centerpiece of an 80-year-old hoax

L egend says the diver drowned retrieving the pearl. Trapped in a giant Tridacna clam, his body was brought to the surface by his fellow tribesmen in Palawan, a province of the Philippines, in May 1934. When the clam was pried open, and the meat scraped out, the local chief beheld something marvelous: a massive pearl, its sheen like satin. In its surface, the chief discerned the face of the Prophet Muhammad. He named it the Pearl of Allah. At 14 pounds, one ounce, it was the largest pearl ever discovered.

A Filipino American, Wilburn Dowell Cobb, was visiting the island at the time and offered to buy the jewel. In a 1939 article that appeared in Natural History magazine, he recounted the chief’s refusal to sell: “A pearl with the image of Mohammed, the Prophet of Allah, is earned by devotion, by sacrifice, not bought with money.” But when the chief’s son fell ill with malaria, Cobb used atabrine, a modern medicine, to heal him. “You have earned your reward,” the chief proclaimed. “Here, my friend, claim this, your pearl.”

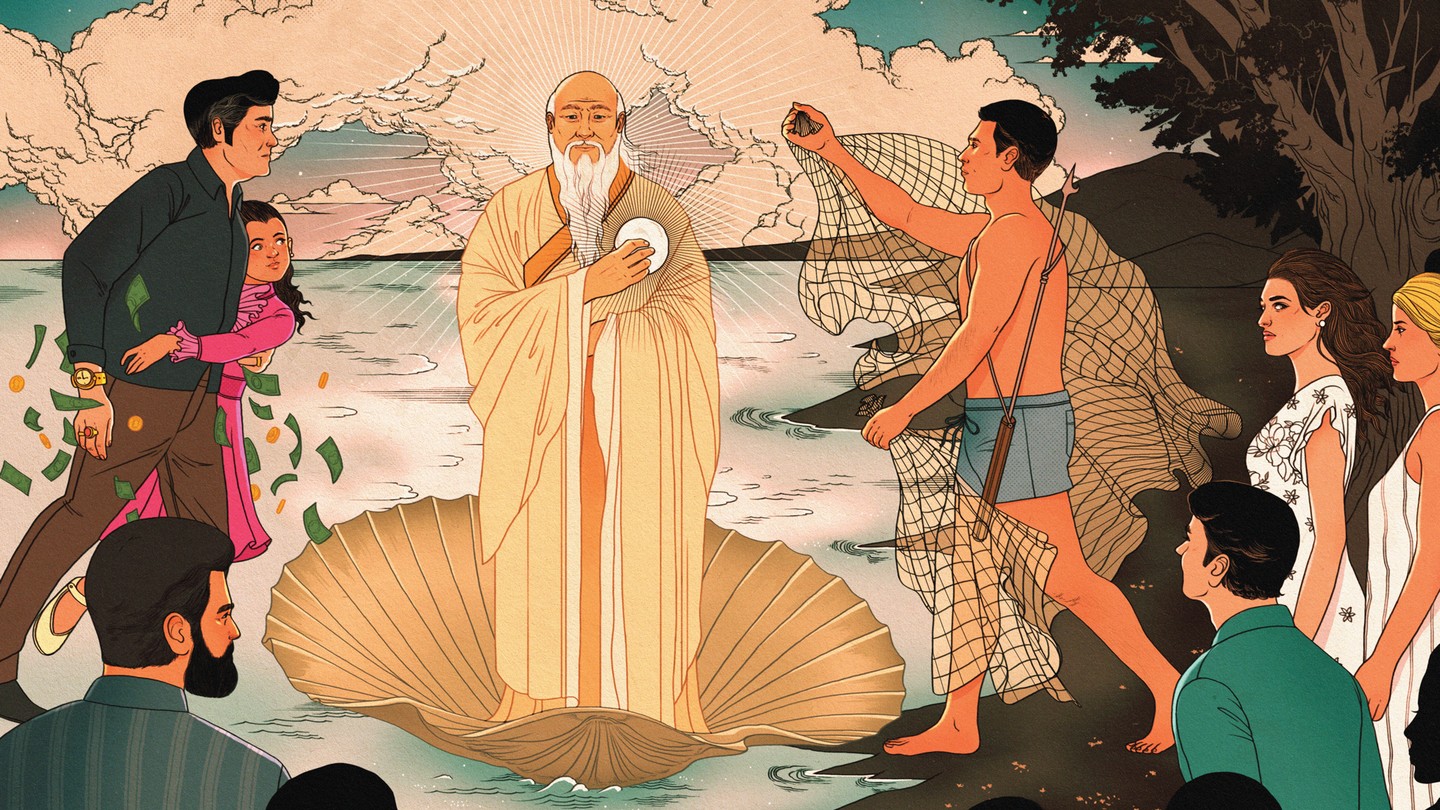

In 1939, Cobb brought the pearl to New York City, and exhibited it at Ripley’s Believe It or Not, on Broadway. There, a new legend emerged, eclipsing the first. Upon seeing the pearl, Cobb said, an elderly Chinese gentleman “of highest culture and significant wealth” named Mr. Lee “burst into an hysteria of trembling and weeping.” This wasn’t the Pearl of Allah; this was the long-lost Pearl of Lao Tzu.

Around 600 b.c. , he told Cobb, Lao Tzu, the ancient Chinese philosopher and founder of Taoism, carved an amulet depicting the “three friends”—Buddha, Confucius, and himself—and inserted it into a clam so that a pearl would grow around it. As it developed, the pearl was transferred to ever-larger shells until only the giant Tridacna could hold it. In its sheen, Mr. Lee claimed, was not just one face, but three.

On the spot, Mr. Lee offered Cobb half a million dollars, saying the pearl was actually worth $3.5 million. But like the principled chief before him, Cobb refused to sell.

The mysterious Mr. Lee returned to China, never to be heard from again. But his spontaneous appraisal—$3.5 million—still forms the basis of a price that has steadily grown, from $40 million to $60 million to $75 million and beyond. And Mr. Lee’s recognition of Lao Tzu’s legendary pearl is at the heart of an 80-year-old hoax that has left a trail of wreckage across the United States—a satin mirage many try to grasp, before the jaws snap shut.

Bits of the legend are true. The pearl really was discovered when a diver drowned; Cobb really did acquire it from the local chief; and gazing at the pearl, you really can discern the face of a turbaned man. The rest is a fantasy Cobb invented.

In the dry hills of Union City, California, I met his daughter Ruth Cobb Hill. Born in the Philippines, she is now 85 years old, a retired clinical psychologist. Facing her wall of artifacts—pottery, bracelets, and necklaces dating back to the Song dynasty ( a.d. 960–1279)—she began excavating the pearl from its foundational myth.

Wilburn Cobb was born in 1903 on Cuyo, an island in the western Philippines. His father was an American mining engineer, and Cobb grew up affluent, with a penchant for adventure. Ruth described him as a brilliant swimmer who would go diving in Palawan’s underwater caves and race with schools of sharks. As he traveled from island to island, he grew enamored of indigenous cultures, and began writing romantic stories about the people he encountered.

“The storytelling part of him was always, always there,” Ruth told me. “He wanted to be a writer.” Cobb studied his pearl, sketched it from different angles, and finally saw the turbaned face, like a figure in a cloud. He called it the Pearl of Allah in heretical, if well-meaning, deference to the chief, who was Muslim—and then put the words in the chief’s mouth, in the pages of Natural History . With a childlike indifference to distinctions of fact and fiction, Cobb seemed to perceive the pleasure of a story as proof of its validity.

By the time he acquired the pearl, Cobb was a husband and a father to eight children, but domestic life never suited him. He pictured himself taking the pearl to America. It wasn’t long before Ruth saw the jewel as a rival. No older than 5, she came upon the pearl one night and kicked it—surely the only time the world’s largest pearl has been treated with such disregard.

Ruth was right to worry; Cobb left for America in 1939. He brought the pearl to Roy Waldo Miner, a curator at the Museum of Natural History in New York, who wrote a letter certifying it as a genuine Tridacna pearl, and “a record specimen.” The Miner letter was enough to land Cobb his contract at Ripley’s, until the novelty wore off.

Cobb’s American adventure meant abandoning his family to the Japanese occupation, which came in 1941. At the age of 9, Ruth witnessed massacres, had her home razed, and lived as a fugitive. Her father’s wartime experience sounds jolly by comparison. He joined the Merchant Marines, working in a ship’s kitchen while in his suitcase the pearl made an unofficial world tour, all the way to India before the fighting got too heavy.

“Psychologically, he really couldn’t separate from it,” Ruth said, even as his life grew increasingly austere. Upon returning from the war, he settled in San Francisco and got a job as a guard at San Quentin State Prison. Cobb cherished the pearl all the more in San Quentin’s spare confines. “A lot of money would be just another headache to me,” he told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1967. “The richest man in the world doesn’t have what I have.”

But what was it worth? Such a singular object was hard to appraise. In a way, the pearl was worth only what someone would offer, and it was toward the end of Cobb’s life—when he flirted with putting the pearl on the market—that the story of Mr. Lee first circulated.

In 1967, Lee Sparrow, who operated the San Francisco Gem Laboratory, helped make the story a reality. “If Cobb was offered $3.5 million,” he told the San Francisco Chronicle, “then that is what it is worth.” But in Sparrow’s estimation, $3.5 million would be the bargain of the century. His laboratory set out to prepare an authoritative appraisal. With a whopping 127,574 pearl grains, Sparrow said, the pearl should be valued at $40 million to $42 million.

The Sparrow appraisal surely flattered Cobb’s fantasy, but though he sometimes considered selling the pearl, he never did. He’d be approached by men who wanted to broker a sale, and leave them vexed.

Cobb’s refusal to sell complicates certain accusations recently leveled against him. In the Philippines today, descendants of the Palawan chief reportedly insist that Cobb was only ever given the pearl as a broker. He was meant to sell it and share the proceeds with the chief. The descendants believe that their family still has a viable claim to the pearl—a matter of symbolic as well as financial importance. In 1996, Filipino President Fidel Ramos declared the South Sea pearl the country’s national gem, and singled out the Pearl of Lao Tzu as the world’s premier specimen.

When Cobb died, in 1979, Ruth was left to settle his estate. Once a rival for her father’s affection, the pearl now became a tax liability. Wanting a second opinion of its value, Ruth consulted a gemological expert at the IRS, and they arrived at a price of $200,000. That sounded fair. Soon after, a jeweler from Beverly Hills said he’d found a buyer.

And so, 40 years after the Pearl of Lao Tzu had come to America, Ruth Cobb Hill met its buyer at a Wells Fargo in San Francisco. Under armed guard, she lifted the world’s largest pearl from its safe-deposit box, and handed it over to a man named Victor Barbish.

I f Cobb wrote the pearl’s original gospel, Victor Barbish was its fundamentalist. He founded a holding company, the World’s Largest Pearl Co. Inc., and named himself president. Then he elaborated on Cobb’s story—“the factual history,” he called it.

During the Sui dynasty ( a.d. 581–618), Barbish said, the pearl’s owner awoke to find a young boy desperate for food and shelter knocking on his front gate, and took him in. One night, the man dreamed that the Pearl of Lao Tzu spoke to him and prophesied that the boy would initiate a new dynasty, “a reign distinguished by a more humane attitude than has prevailed heretofore.” Sure enough, the boy grew up to become Li Shih-Min, a founder of the Tang dynasty.

Barbish also resolved a key logistical hitch in Cobb’s story: how the pearl ended up off the coast of the Philippines, some 1,800 miles away from the seat of the Chinese empire. Still snug in its shell, he said, the pearl found its way onto a trading ship during the Ming dynasty ( a.d. 1368–1644), and was swept overboard in a typhoon.

He claimed to have learned these facts from a member of Mr. Lee’s family in Pasadena in 1983. With the help of a former CIA agent named Lewis Maxwell, Barbish said, he planned to sell the pearl to the Lee family.

Yet something always seemed to thwart the pearl’s sale. The problem wasn’t that Mr. Lee never existed—that he was only ever a Wilburn Cobb invention—it was a series of action-packed calamities of the sort Barbish seemed to attract. In Japan, Barbish said, Mr. Lee gave Maxwell a check for a $1 million down payment, but after returning home to Alaska, Maxwell bled to death during a botched bypass surgery. The check disappeared, and Barbish never heard from the Lees again.

Lewis Maxwell is just one of many names that float through the pearl’s history with Victor Barbish. Doctors, generals, princesses—there usually was a real figure somewhere behind the name. Like Cobb, Barbish sensed that the story could be worth more than the actual object. And in Barbish’s telling, the story of the pearl always ended with you becoming rich.

When I began looking into the Pearl of Lao Tzu, I heard about a woman in Florida who knew more than anyone else about Victor Barbish’s 25-year ownership. She’d even written a memoir about Barbish, I was told, but was sitting on it for fear of being sued, or worse.

I met Laura Lintner-Horn in Bradenton, Florida, in October, and over the course of several days, she told me how she had lived with Barbish’s family, on and off, for 50 years—from when she was a little girl until she met her third husband—never questioning his claims or disobeying his orders. She’d held the Pearl of Lao Tzu in her hands, and thought Barbish was here to fulfill its ancient message of peace. Indeed, she’d have done anything for the man she believed to be her father.

Laura became an unknowing accessory to Barbish’s schemes, all the while believing equally in the legends of the pearl and the man. By the time she learned she’d been living a lie, she’d endured unimaginable tragedy, and had nothing left. “Everybody ends up defending the pearl until they lose,” she said. “And they lose big.”

The story she told, and what I discovered during my own yearlong pursuit of the pearl, braided fact and fiction into a theater of the American absurd. From contract killings to alien abductions, Chinese emperors to Osama bin Laden, the Pearl of Lao Tzu’s story kept getting weirder with every detail I uncovered. And, as I’d learn, this artifact has come back on the market, and is only waiting for the next set of hands to pry it loose.

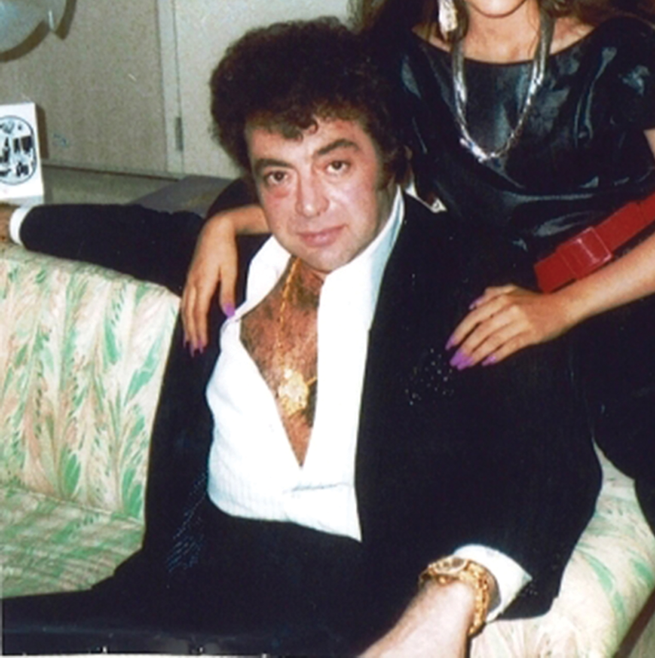

F or 10 years, Laura has been trying to piece together the life of Victor Barbish, yet even basic facts are difficult to recover. He was a man who praised America as a place where a citizen “could be anything he or she wants to be,” and took full advantage of the national tolerance for self-invention. He said he was a monk, a prizefighter, a CIA agent, an opera singer. He was the business partner of Sammy Davis Jr., the lover of Sophia Loren. He was poisoned, shot, imprisoned in war, possessed by demons. His family calls him a visionary; most others call him a con artist.

Barbish claimed to be the son of Al Capone, and he dressed the part, wearing open jackets, his bare chest heaped with gold chains. Whenever he happened to be near Mount Carmel Cemetery in Hillside, Illinois, he’d place a Cuban cigar on Capone’s grave site, a tribute to “Dad.” In fact, his father was a butcher named Lester Barbish, who married Helen Ruben and had a boy, Lawry Barbish, in New Castle, Pennsylvania.

The man we know as Victor Barbish makes a debut in the public record in 1970, in La Verne, California. The city council prohibited gambling, but Barbish was running a bridge parlor at Vic’s Steak House, his restaurant and nightclub. Reading about his decadelong fight to legalize his operation, one gains a kind of admiration for his tenacity. To stop the constant raids on his bridge parlor, Barbish threw everything at the city council. He switched from card games to bingo, and said the proceeds would go to youth sports: He’d fund the completion of a downtown minipark. But La Verne didn’t want his money, or him. “I certainly would not want the minipark known as ‘the park that Vic built,’ ” one city councilman said. When flattery failed, Barbish unsuccessfully sued the city, demanding to know “the price of becoming a respectable citizen.”

He moved to San Bernardino and founded the Church of All Faiths in a former five-and-dime store, using religious exemptions to start a bingo game there. Now he was Reverend Vic Barbish, ordained by the Universal Life Church of Modesto, a mail-order service. He published apocalyptic sermons in the local newspaper, while his bingo games took in about $80,000 a month. The city government finally realized he’d been investigated before, and revoked his gambling license.

No matter what Barbish tried, he couldn’t shake a scent of the illicit; the people of San Bernardino thought he had ties to the Mafia. He needed something to legitimize him, something solid. He found that something in 1979, when word came to him that Wilburn Cobb had died. The world’s largest pearl was for sale. The price of becoming a respectable citizen: $200,000.

In 1985, Barbish moved to Colorado Springs and reinvented himself yet again. As president of the World’s Largest Pearl Co., his name in The Guinness Book of World Records , he fostered an image of prosperity. A driveway of luxury cars led up to an enormous house filled with jade dragons, stuffed lions, a photograph of Princess Diana and Prince Charles personally addressed to Barbish’s glamorous wife. He ingratiated himself with the city’s jewelers, real-estate agents, and car dealers. He invited the police for dinner.

Barbish would dazzle you with gaudy opulence. Then he would ask for an investment, or perhaps a short-term loan— just a few hundred thousand, say—to finesse the final touches of a blockbuster deal.

“Victor was constantly saying, ‘I’m working on a $20 million loan on the pearl, and it’s going to be coming any minute,’ ” one of his marks told me. Or he’d say he had a buyer: Ferdinand Marcos, Whoopi Goldberg. But at the last possible moment, the deal would fall through—if not from some calamity, then because Barbish was just too principled. In the mid-’80s, he said, an excommunicated Iranian princess had brokered a $40 million sale on behalf of a group in Europe. But when Barbish learned that the buyers were “all of a criminal, unscrupulous origin,” he called it off.

At other times, fate would intervene to protect the sanctity of Lao Tzu’s pearl. In 2004, Barbish told Aaron Klein of WorldNetDaily that he’d received a $60 million offer on behalf of a foreign buyer named Osama bin Laden back in 1999. According to Barbish, bin Laden had intended to purchase the pearl as a gift for Saddam Hussein, “to unite the Arab cultures.” The deal was in place, but bin Laden’s representatives were stopped at the Canadian border.

When Klein, now the Jerusalem chief of Breitbart News , wrote about the deal, Barbish suggested that it established a link between bin Laden and Hussein—a crucial missing piece of George W. Bush’s justification for invading Iraq. “I just couldn’t sit back and listen to these lies about our government and President Bush,” Barbish said. “Bin Laden tried to purchase my pearl as a gift to Saddam, and Saddam wanted to accept it.” (Klein wrote that he was provided faxes documenting this historic deal, but when I reached him for comment, he said he couldn’t find them.)

Written down, such stories seem so artless, it’s hard to imagine how Barbish passed them off. After all, his targets were savvy, successful people. But they had one thing in common: a fatal thread of greed that Barbish masterfully teased out.

S ome fought back. Through the 1980s and ’90s, hardly a month passed without one legal action or another, brought by a large cast of characters claiming a share—$250,000 here, $500,000 there—of the Pearl of Lao Tzu.

A constant presence in the legal saga was Peter Hoffman, the Beverly Hills jeweler who’d brokered the purchase from Wilburn Cobb’s estate in 1979. When a Colorado judge, fed up with all the legal wrangling, ordered the pearl to be sold at auction by August 1990 to settle the debts, Hoffman went to work. The bidding would begin at $10 million.

Hoffman still owns a one-third stake in the pearl, and he’s always seen himself as the pearl’s rightful guardian, the only one who could successfully market it. Wilburn Cobb, he once told a reporter, “saw me in a dream with the three sages, Buddha, Confucius, and Lao Tzu, who said I would be the next caretaker of the pearl.”

In May 1990, Hoffman exhibited the pearl in a vault at Studio City, in Los Angeles, the last time it was seen in public. On black velvet and gold lamé, it elicited gasps from reporters at a press conference, where Hoffman said the pearl had been cultivated by Lao Tzu’s descendants. Indeed, “the pearl’s purported spiritual powers” were far more important to him than the money, which he pledged to use “to benefit mankind.” As for that money, he expected the pearl to sell for $25 million to $50 million. (Citing too much “fake news” about the pearl, Hoffman declined to comment for this story, but noted that it “should be properly referred to as a priceless famous historical artifact.”)

Hoffman has claimed that he was close to a sale several times in the ’80s and ’90s. Ferdinand Marcos was supposed to buy it, but was deposed before a sale was finalized; a baroness briefly had the sultan of Brunei intrigued. But his efforts ultimately led nowhere. The deadline passed, and the pearl drifted back into limbo, sealed in a safe-deposit box—right where Victor Barbish wanted it.

For more than 20 years, the Pearl of Lao Tzu has remained in Colorado Springs. There, its secret is kept safely out of sight: It isn’t worth what the owners claim. In fact, it isn’t even a real pearl—at least, not as you might think.

If someone says he owns a 14-pound pearl, you’ll probably picture one of those familiar, very precious little gems, and multiply the value out of all proportion. Seemingly to generate such warped calculations, the appraisal prepared by Lee Sparrow in 1967—$40 million to $42 million—cherry-picked from the 1939 letter written by Roy Waldo Miner, the Museum of Natural History curator. Miner had asserted that the specimen “can truly be called a pearl.” With this established, Sparrow proceeded to calculate the object’s value as though it were one of those tiny round gems blown up to Guinness -record size.

Explore the June 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

But elsewhere in the Miner letter, the curator terms the specimen a “pearlaceous growth,” and stresses that it ought not to be classified as a precious pearl. The gems we commonly know as pearls are formed within the organic tissue of saltwater oysters, whose inner shells possess nacre, or mother-of-pearl, which generates a pearl’s signature luminescent sheen. Compared with these gems, Tridacna -clam pearls are more like porcelain. Indeed, the Pearl of Lao Tzu cuts an ugly figure. Some might liken it to a lump of white clay; others might think it’s an alien egg.

Under U.S. trade law, it’s perfectly legal to call such objects pearls; any shelled mollusk—even a snail—can make a pearl. But gemologists traffic in precious pearls, and discard the rest with a pejorative classification: calcium-carbonate concretions.

What was Sparrow doing? I located a colleague of his, who worked with him for 20 years (Sparrow passed away in 1990), and she recalls him as credible, even admirable. But with the Pearl of Lao Tzu, he was pulling a stunt. “I laughed my way through that whole thing,” she told me. She described how Sparrow was egged on by excited colleagues to inflate the number, until, in a collective frenzy, they reached $40 million to $42 million. If the pearl could attract a buyer at that price, then surely Cobb wouldn’t refuse to sell (and Sparrow would get a handsome commission). “It’s not like you’re breaking the law,” she added. “It just makes you look silly.”

The Sparrow appraisal left room for the pearl’s “historical significance” as well, claiming that the pearl had been “carbon dated to be ±600 years old.” But Michael Krzemnicki, who directs the Swiss Gemmological Institute and has written extensively on techniques for dating pearls, told me there’s no record of the pearl’s ever having been subjected to radiocarbon dating.

None of these facts inconvenienced Victor Barbish. In 1992, he commissioned a fresh appraisal, something to replace that of the deceased Lee Sparrow. Michael “Buzz” Steenrod, a former video-equipment salesman who worked at All That Glitters, a jewelry store in Colorado Springs, prepared the document.

While Sparrow only said the pearl could be about 600 years old, the slippage is complete in Steenrod’s work. “It has been carbon dated to 600 b.c. ,” his appraisal avers. All things considered, he estimated its worth at $52 million. (Steenrod declined to comment.)

It’s hard to blame those who fell for such fabulous appraisals, when the media provided no bulwark against them. Time after time, journalists failed to apply even the slightest pressure to the story. The pearl is “an estimated 6,000 years old,” the Los Angeles Times reported . It has been valued at $42 million, Channel 5 News in L.A. said. An anchor at CNN asked her audience: “Could you imagine the oyster?”

Victor Barbish knew where the real money was—not in actual clams, but imaginary oysters.

On no one did the spell work so well, or last so long, as Laura Lintner-Horn. She was the perfect candidate for life in Barbish’s hall of mirrors. Born in 1953 in Maywood, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, Laura was adopted by her grandparents at the age of 3. Her parents had divorced, and it was considered seemlier for Laura’s mother to give her up, the better to attract another husband in their conservative, Italian Catholic neighborhood. Rather than being candid about the arrangement, however, Laura’s grandparents presented themselves as her parents, while her biological mother and aunt became her older sisters. Laura never doubted these relations, even as her classmates taunted her: “Your mother has gray hair! Your mother’s an old woman!”

Victor Barbish met Laura’s “sister”—actually her aunt—at the Paradise Ballroom in Chicago in 1957, and they married. With his usual creep toward fabrication, he began putting it out that he’d had a one-night stand with Laura’s biological mother and that Laura was his daughter. And so Barbish’s revelation that her parents were really her grandparents only gave way to another primal deception: that he was her father. Until his death, in 2008, she believed it.

She wanted to believe it. “I wanted a normal family so bad,” she told me. “I worshipped the Barbishes.” But while Barbish absorbed her into his family, she was always second-class, always playing catch-up in his affections. Every time she cleaned his house or worked without pay, she said, “I did it out of my heart.”

One gets the sense that Barbish enjoyed seeing how far he could stretch Laura’s faith. When she divorced her first husband, whom she’d impulsively married at the age of 18 and who’d turned out to be abusive, Barbish told her he’d had him killed, and Laura didn’t learn otherwise until she ran into the man in Colorado Springs some 30 years later. When asked what had really happened, Barbish told her: “Let’s not go there, Laura.”

And so she didn’t. Barbish wielded such supreme authority, she didn’t even doubt his live performances of alien abduction. He’d be driving down the highway, and his head would suddenly wrench back and his eyes would roll: The aliens had snatched his body. Laura would grab the wheel and shake him—“Please, Vic, wake up, wake up!”—and in the nick of time, he’d come to his senses, with no memory of his latest close encounter.

L aura made her career in loss prevention for a department store, stalking shoplifters in a trench coat like her role model, Columbo. She’d wrestle them to the ground; once she jumped through the window of a car to prevent an escape, only to have a gun put to her head. “I was such a bitch,” she recalled. “I prided myself on that.”

But she had a blind spot for the thief in her life. Looking back, she’s astonished by her gullibility, which she credits to the atmosphere of the Barbish home, describing it as cultlike. “You asked permission for everything,” she recalled.

Laura’s major losses began on August 30, 2000. Lisa, Laura’s daughter with her first husband, had herself survived a physically abusive marriage, and Barbish had directed her to move to the town of Stockton, Illinois, to put her life back together. In Stockton, Lisa struggled with depression, started drinking, and lost her driver’s license. But that didn’t stop her from driving; she just evaded police along back roads, where the corn grew high in summer.

At an intersection that August morning, a fully loaded 18-wheel truck hit Lisa’s car, driving it 200 feet into the fields, and killing her instantly. “I remember going through the cornfields just looking for things,” Laura said. She still has the items she recovered that day: a hubcap, a shoe.

At the time, Laura was married to Phillip Lintner, an Elvis Presley impersonator. He’d raised Lisa from the crib, and when she died, Laura said, he destroyed himself in grief. He drank cheap liquor, smoked cigars, and stopped singing. Thirty days after receiving a diagnosis of stomach cancer, Phillip died, on Christmas Eve 2001.

Laura retired early, and drew closer to Barbish. In addition to her pension, she had money from the sale of a house, as well as life-insurance payouts from her husband’s and daughter’s deaths—hundreds of thousands of dollars. Barbish convinced her that in her grief, she wasn’t thinking straight, and that people would try to take advantage of her. Wouldn’t it be prudent to turn everything over to him, to let him invest the money and steward her accounts?

In 2005, Barbish moved one last time, to Sarasota, Florida. In typically grand fashion, he took up residence in a $1.5 million house, established a jewelry store in the city’s historic downtown, and dissolved the World’s Largest Pearl Co. After all these years, he said, he’d “become weary of the unceasing evils” of those who’d tried to possess his pearl. “It draws the wrong type of people,” he told the Associated Press . “It was made to do something good.”

And so he created the Pearl for Peace Foundation , a registered nonprofit organization that pledged to support law enforcement. Anyone who paid a membership fee—from $25 to $600—received a golden badge with an image of the pearl at the center, and a membership card depicting a dove soaring with the pearl in its talons: to unite and protect us all . President George W. Bush was named member No. 1.

Barbish’s family says the foundation reflected his passion for America. “His whole life was about trying to do something great for the country,” his son Mario told me. Indeed, the foundation was a precursor to the Blue Lives Matter countermovement. “He knew what was coming,” Mario said, “the disrespect for law enforcement in our country.”

Without access to her own money, Laura was compelled to move to Florida to help care for Barbish in his twilight years. He installed her as the manager of his jewelry store and the nominal director of the foundation. On everything from checks to tax returns, Barbish had Laura sign his name. She thought she was doing solid charitable work. Every day, she randomly selected 30 names from the phone book and called for donations. Barbish had prepared the script: The money will be spent on disabled agents, death benefits, bulletproof vests. The goal was to donate $20 million. Laura estimates that in just two years on the Gulf Coast, Barbish took in about $5.5 million through a variety of cons.

The Pearl for Peace Foundation’s mission statement ended with what can be read as a blessing, or a curse: “Let the Legend and the Legacy live on from generation to generation …”

When I visited Laura in Bradenton, just outside Sarasota, in October, Hurricane Nate had recently struck the Gulf Coast, and trucks were still cruising around town, collecting broken palms. She lives in a bungalow with her third husband, Robert Horn, along with five borzoi dogs, two cockatoos, and a foulmouthed 68-year-old parrot that once belonged to Victor Barbish. Halloween was coming, and the couple had decorated, submerging a plastic replica of the Pearl of Lao Tzu in water: the brain in a vat.

The story of Laura and Robert’s union is also the story of her final break with Barbish. While operating the foundation, Laura liked to walk her borzoi through the streets of old Sarasota, and she’d be asked whether she’d ever seen the man with the same striking breed of dog. When she saw the two out walking, she approached the man, who introduced himself as Robert Horn. In a publicity stunt for the jewelry store, they had a Wiccan minister marry their borzoi on the street out front. The humans married soon after, in 2007.

Robert was excited to join a large Italian family, headed by a man who struck him as “the godfather of Florida,” the owner of the world-famous Pearl of Lao Tzu. One day, he heard his father-in-law on the phone, sounding distressed. Barbish had found a buyer in New York City, he overheard, but didn’t have the cash in hand to securely transport the pearl. The deal was in peril. Robert leaped at the opportunity to help his new family. It would be only a few months, anyway, until the sale cleared. An accountant by training, Robert still can’t fathom the spell he was under when he cut Barbish a check for $100,000.

Although Laura suffered from fibromyalgia, Barbish made her sleep in the jewelry store to protect the merchandise. When he started telling her that jewels were missing from the safe, and accusing her of negligence, Laura thought she was losing her mind. Relying on her years in loss prevention, she staked out the store from a nearby restaurant, and saw Barbish entering the premises after hours. The discovery prompted her to finally turn an investigative lens on her father. She began questioning him about where the foundation’s money had gone, and the exact nature of his deals. Barbish reacted with hostility to her sudden back talk.

When he died, peacefully at home in January 2008, his widow, Laura’s aunt, made keepsakes with his ashes and distributed them to his four children. Laura didn’t get one. She obtained her adoption papers, from when her grandparents became her guardians, from the state of Illinois and didn’t recognize the name of her biological father, Richard Walters. By the time she tracked him down, she found only his ashes in an urn. He’d died in 2007.

So now she knew. A 50-year hypnosis broke, and Laura began to perceive the full fraudulence of her past. She told Robert to hire a lawyer to get his money back. (Her own, she realized, was long gone.) The Barbish family took this as a direct assault, and the couple claim that Mario Barbish, the executor of his father’s estate, threatened to have them killed if Robert pursued his money. Laura says it wasn’t the first time she feared for her life; she’d earlier hidden a letter: If my husband or I come to harm, please investigate. (Mario denies having issued the threat, calling Laura a “delusional woman” and disputing her version of events.)

Yet to his dying breath, Victor Barbish had seen himself as the real victim, a “passionate romanticist” who’d placed too much trust in more-imperfect souls. “I almost was a billionaire,” he lamented in his will, “but due to dishonest law firms, banks and brokers, I got swindled out of my wealth.” Still, he took solace that his legacy was secure. “Fortunately you, my loved ones, were protected,” he wrote. “You have an article in your corporation that is valued between $38–$60 million.”

Beneath a signature that doesn’t appear to be his, Victor Barbish added an apt motto for his life: “This is who I am and wish to be.”

With the help of Ebby Salinas, a former partner from loss prevention, Laura has been deconstructing Victor Barbish’s lies in her memoir, The Last Con. There’s an element of vindictiveness to the project. When it’s finally finished, Laura and Ebby intend to self-publish and tour it through the cities where Barbish lived, laying waste to the myths he constructed. They want to see The Last Con made into a movie, a stage play, an episode of American Greed .

Whatever success The Last Con enjoys, it won’t make up for Laura’s losses. For that, she’s recently turned to a faith her grandmother once practiced in secret—metaphysical Christianity. She’s become an energetic healer in the church, according to which death is merely a transition from one form of energy to another. “Lisa is with me all the time,” Laura told me—manifesting as a barn dove, or purple flowers. Her connection to her deceased husband, Phillip, isn’t so vivid, but in times of crisis, she’ll hear a song by Elvis, and know he’s there.

Before leaving Florida, I visited the lawyer for the Barbish estate, who’s functioned as something like the janitor for the aftermath. I saw Robert Horn’s name on a list of claims, along with dozens of others. Despite the alleged threats, Robert had pursued his money after all. But Barbish’s other assets couldn’t come close to satisfying everyone. Only a sale of his share in the pearl could initiate the needed cascade. Even the estate’s lawyer said he was owed half a million dollars. When I asked why on Earth he kept working the case, he said he has to know how the story ends.

For decades, the pearl case has dragged on in court, as litigants have tried to finally force a sale and get their money back. The original players are passing away—only Peter Hoffman remains—and the old animosities are enacted by latecomers, like a famous show revived by understudies. This state of paralysis was determined by the fates of two women, who died without ever hearing about the Pearl of Lao Tzu.

A fter midnight on March 25, 1974, Ann Phillips was riding in a Cadillac with her husband, Tom, on the Hancock Expressway, in Colorado Springs. When a police light swirled behind them, Tom dutifully pulled over. But instead of police, masked men emerged from the car. They shot Ann dead, knocked her husband unconscious, and fled into the night.

Twenty months later, on the evening of November 23, 1975, a man answered the door at the house of his aunt Eloise Bonicelli on West Arvada Street, also in Colorado Springs. As soon as the nephew opened the door, a stranger in a stocking cap shot him in the chest and stormed the house. The nephew escaped to the basement, and minutes later found his aunt in the fetal position on her bedroom floor, dead from a bullet through the heart.

For 25 years, the murders went unsolved. But as it turned out, the husbands of Ann Phillips and Eloise Bonicelli had two things in common: They’d both hired a hit man to kill their wives, and they both became investors in the Pearl of Lao Tzu.

Joseph Bonicelli owned legitimate businesses in Colorado Springs—a bar, a used-car lot, a construction company—but his reputation was far from spotless. Many former acquaintances recall him as a mobster, or at least a “gangster type”; he’d owned a massage parlor where a woman had been killed before it burned down. Others remember him as a man who dreamed big. In the 1970s, he built a nascar -style racetrack, the Colorado Springs International Speedway, out near the Air Force base.

Tom Phillips also owned a bar, but he was never particularly entrepreneurial. He was a heavy gambler, known as “Mr. P.” in Las Vegas, where the house always won. Yet he had an uncanny knack for getting close to people with money, people like Joseph Bonicelli. Even those who loathed Phillips grant that he was charming.

By his own admission, Tom Phillips contracted the murder of his wife to collect on her $300,000 life-insurance policy. He paid a local barber to arrange the hit, and staged himself as the victim of a robbery-homicide. So pleased was Phillips with the barber’s service, he recommended it to Bonicelli, who was staring down a costly and bitter divorce with Eloise. Neither man was ever brought to justice—not while alive, anyway.

I n Colorado Springs today, some controversy remains over why Bonicelli was finally accused of arranging Eloise’s murder, several years after his death in 1998. Her children say they were motivated to reopen the case by a desire to honor their mother’s memory; others claim that it was an attempt to wrest control of Bonicelli’s estate from his new wife and her daughter, to whom he’d left everything.

The means by which Bonicelli was posthumously tried have certainly invited questions. In exchange for testifying against the dead man, Tom Phillips was granted full immunity for arranging his own wife’s murder. Even though he’d been the connection between Bonicelli and the hit man, and committed the exact same heinous crime, Phillips was allowed to go free. He has since died.

Based on the Phillips testimony, the children of Eloise brought a civil suit against their dead father’s estate, which possessed at least one major asset that they knew of: a one-third stake in the Pearl of Lao Tzu. Around 1984, Phillips introduced Bonicelli and Barbish, and Barbish brandished a contract for a sale purportedly authored by Ferdinand Marcos. Bonicelli had just sold his speedway for $750,000, and he sank the whole sum into the pearl. Naturally, the sale fell through, and Bonicelli never got over it. In his final years, he’d sit at his kitchen table with a .38, promising to kill Phillips on sight. As for Barbish, Bonicelli said he wanted to blow up his house.

In 2005, seven years after his death, Bonicelli was finally found responsible for Eloise’s murder. The judgment was directly tied to the value of the pearl. Though defense lawyers produced records showing that it had only ever sold for $200,000—when Barbish bought it from Cobb’s estate—the testimony of Buzz Steenrod carried the day. He had spruced up his previous appraisal, adjusting for “economic fluctuations,” and set the pearl’s value at $59.75 million. Before a jury, he explained how the pearl had been cultivated by Lao Tzu more than 2,500 years ago. “His thought was that it would symbolize peace and unity of all mankind,” he testified. “This is not a conventional pearl.”

The jury awarded Eloise’s children what was reported to be the largest wrongful-death judgment in Colorado history: $32.4 million.

Today, the Pearl of Lao Tzu is legally divided between Peter Hoffman and the estate of Victor Barbish; Eloise Bonicelli’s children are owed half of Barbish’s share in the event of a sale. The court battles have waylaid efforts to sell the pearl. But toward the end of 2017, I began to hear whispers that the path might be clearing.

Curious to know the status of the pearl, I met Mario Barbish, Victor’s son and the executor of his estate, for lunch at an outlet mall on the outskirts of Colorado Springs. “I totally believe in the entire story,” he told me. “I don’t question it at all.” He believes the pearl was cultivated in ever-larger clams through the centuries; he believes Lao Tzu’s amulet is still lodged deep inside the jewel. “It’s like I’m a Christian,” he said. “I believe in Jesus Christ. Can I prove it? No, it’s a belief.”

Mario also believes that the pearl’s reputation has been unfairly sullied. When I met him, the #MeToo movement had been in the news, and Mario likened it to what’s happened to the Pearl of Lao Tzu. “You can discredit somebody’s character, and it never goes away,” he said. What the jewel needs is positive writing, positive promotion, maybe a world tour. “It’s really time to blow life back into the pearl.”

To that end, Mario showed me a brochure he’d compiled. It included photos of the pearl laid out on what appeared to be a beach towel, and several pages of text relating the legend. It was almost sad to see Wilburn Cobb’s fantasy ground up like this:

The Pearl was indeed born of the clam but it was with the guidance in nurturing interference of man and brought it to it’s [sic] present state of beauty and rarity … who will be the benevolent guardian that will possess this priceless, historical, and significant scientific, One of a Kind Artifact.

Only such a campaign could attract the right buyer, Mario insisted. As for the price, he produced a copy of the Sparrow appraisal, and cited $100 million as his benchmark.

In the final analysis, Mario said, the Pearl of Lao Tzu is priceless. When I asked whether he’d consider selling it through an auction house, he demurred. “You want the auction house to think like you do,” he said. “That attitude is what’s going to bring the money.” If a house has its doubts about the pearl’s pricelessness, why would he entrust it to them?

And the houses certainly do seem to have doubts. I obtained a memo circulated to the owners in August 2016 by David Beck, a lawyer in Santa Cruz, California, who represents the interests of a long-deceased man. (“I started working the Pearl case when I was a new attorney in the mid-1980s,” Beck wrote. “Now I am nearing retirement.”) Slowly but surely, he’d seen the many claims on the pearl defeated; only Joseph Bonicelli’s has held up in court.

At the time of the memo’s writing, Beck stood as the last lawyer still trying to wrestle money out of the pearl. In the final episode of his 30-year struggle, he’d filed a motion to compel a sale, trying to initiate the long-awaited settlements. He’d wanted to understand how such a sale might occur, and he’d asked the esteemed natural-history department at Bonhams, the British auction house, what it would look like to sell the pearl.

The department prepared a proposal. But it showed no $100 million figure, no $75 million, no $42 million. Instead, Bonhams offered an estimate of $100,000 to $150,000. “The Pearl has no value except for any historical value there may be,” Bonhams said. “Beyond that, it is a mere curiosity.”

Beck’s memo was met with silence.

O n February 28, 2018, a United States District Court denied Beck’s motion. And so, after more than 30 years, the final claim on the Pearl of Lao Tzu was vanquished.

But obstacles to a sale remain. Mario Barbish told me that Asia would be his ideal market. But because the Tridacna clam is an endangered species, in order to export the pearl, the Philippines would probably have to endorse the transaction—an unlikely scenario.

A buyer must emerge from within the United States, but the pearl’s beauty is lost on many Americans. Newspapers have described it as “wrinkled,” a “deformed brain,” “a blob.” Its ungainly size means that it will never be seen as jewelry; one attorney said, “It’s not the sort of thing you wear around your neck unless you’re the Incredible Hulk.”

Perhaps its status as the world’s largest pearl would be sufficient enticement, but even that mantle is threatened. In 2016, a fisherman from Palawan came forward with a specimen he’d discovered 10 years earlier when his anchor snagged a giant clam. (He’d been keeping the pearl under his bed as a good-luck charm.) While it hasn’t been officially verified, this pearl reportedly weighs 75 pounds, dwarfing the Pearl of Lao Tzu’s Guinness record. As David Beck observed in his memo to the owners, “We may have missed our moment.”

A day after the motion was denied, I called Mario Barbish. He wanted to know the status of my story, which he hoped would focus on the pearl’s beauty and religious significance. When I described what I had learned, his affable tone rocketed to a register of high indignation. The curse of the pearl, he said, was people like me, who sought to discredit the legend. I couldn’t know the truth; I hadn’t spoken with Victor Barbish, or Lee Sparrow, or Wilburn Cobb. “You’ve never seen the pearl. You’ve never seen the growth lines. You don’t know anything about the pearl.”

Only Mario had the documents proving the valuation beyond a reasonable doubt, but when I asked him to produce them, he refused: “I could, but I’m not.” He seemed to find me pitiable. “The pearl would amaze you if you just held it in your hands,” he said. “A lot of this garbage you’re spewing out of your mouth, you would let it go, because you’d feel that intrinsic value just holding the pearl.”

The Pearl of Lao Tzu isn’t a gem, Mario told me; it’s a “religious artifact.” And just as if the Shroud of Turin went up for auction, he said, those who believe are the ones who will bid. The appraisals will become credible, as if by magic, once you put your faith in the story. (Not the Bonhams appraisal, however; Mario said, “They’re out of their mind.”) That leap of faith will be the sign that Lao Tzu’s pearl has found its true guardian.

When I hung up, I thought of something Wilburn Cobb’s daughter Ruth had told me in Union City. We were discussing the new, 75-pound pearl and what its discovery meant for the Pearl of Lao Tzu. Cobb’s pearl was still the famous one, she said. “But the fame came from the stories, and my father started that. And I don’t know what that brings.”

The pearl’s long, destructive fiction finally ends with the owners now left holding what is likely the world’s second-largest pearl—a bogus religious artifact—seemingly unable to accept the truth, and escape. If there is something mystical about the Pearl of Lao Tzu, it’s the story’s strange tendency toward repetition. Stare long enough, and the owners’ stubborn faith looks like that of Victor Barbish, who stitched myths together and called them history, or like that of Wilburn Cobb, who never relinquished his romance. They begin to seem like the diver, who drowned all those years ago, when he glimpsed that first fateful flash of white.

This article appears in the June 2018 print edition with the headline “Chasing the Pearl of Lao Tzu.”

Lao Tzu: The Founder of One of the Three Pillars of Traditional Chinese Thought

- Read Later

Lao Tzu is traditionally regarded as the founder of Taoism, a school of thought that developed in ancient China. Taoism is seen as one of the three main pillars of traditional Chinese thought. The other two pillars are Buddhism, which was transmitted to China from India, and Confucianism, which was founded by Confucius. Thus, Lao Tzu is regarded as a very important figure in Chinese history, and even revered by many as a deity in the Taoist pantheon.

The Debated Existence of Lao Tzu

Unlike Confucius, Lao Tzu is a much more difficult character to pin down. For a start, some modern scholars are skeptical about his existence, and argue that there is no ‘historical’ Lao Tzu, and that he is an entirely legendary figure.

According to Chinese tradition, however, Lao Tzu lived during the 6th century BC. The ancient Chinese historian, Sima Qian, said that Lao Tzu was a contemporary of Confucius. In addition to this, a biography of Lao Tzu can be found in Sima Qian’s work, the Shiji , known also as the Records of the Grand Historian .

Confucius Lao-tzu and Buddhist Arhat ( 三 教) ( Public Domain )

- An honored Zhou Dynasty warrior, buried with a chariot and horses, has been unearthed in China

- Did Ancient People Really Have Lifespans Longer Than 200 Years?

Sima Qian’s Shiji

In Sima Qian’s Shiji , it is written that Lao Tzu was a native of the state of Chu, which is located in what is today the southern part of China. It is also written in this ancient source that Lao Tzu’s personal name was Li Er ( 李 耳), and that he served as a keeper of archival records at the Zhou imperial court. There have also been claims that Lao Tzu was consulted by Confucius on certain matters of ritual, and subsequently heaped praises on him.

Records of the Grand Historian ( Public Domain )

Sima Qian also wrote that Lao Tzu lived in the state of Zhou long enough to witness its decline. As a result, Lao Tzu decided to depart. When Lao Tzu arrived at the northwestern border that separated China from the rest of the world, he met an official in charge of the border crossing by the name of Yin Xi.

It was this official who requested Lao Tzu to put his teachings into writing. The result of this request was a book which consisted of about 5000 Chinese characters, and is known today as the Tao Te Ching (道德经). Lao Tzu seems to have disappeared after this, and neither his date nor place of death is recorded in Sima Qian’s account.

The Tao Te Ching

The Tao Te Ching is undoubtedly the work Lao Tzu is best known for. Additionally, it is one of Taoism’s major works. Nevertheless, it may be pointed out that the authorship of this important piece of writing has been debated throughout history.

For instance, it has been suggested that that the text was not written by a single author, but by several different authors. Additionally, some have speculated that the contents of the Tao Te Ching were first circulated orally before being written down.

Ink on silk manuscript of the Tao Te Ching, 2nd century BC, unearthed from Mawangdui. ( Public Domain )

On the one hand, it has been argued that it was Lao Tzu’s disciples who kept their master’s teachings alive through oral transmission, and the lessons were later compiled by one / several of Lao Tzu’s students.

It may be also possible that the compiler(s) of the Tao Te Ching had access to other oral traditions. In this case, it would mean that the Tao Te Ching contained not only the lessons of Lao Tzu, but potentially of other Chinese sages as well.

According to Chinese legend, Laozi (Lao Tzu) left China for the west on a water buffalo. ( Public Domain )

- The Colorful Folklore Behind the Flaming Mountains of Turpan

- Our Ancient Origins: KALI YUGA, the Age of Conflict & Confusion - Part 2

Regardless of its origins, the Tao Te Ching and the philosophy it expounds is argued to be a way of thinking that was in direct opposition with that of Confucianism. Although both schools of thought addressed the social, political, and philosophical questions faced by ancient Chinese society, each took a distinct approach. Confucianism, for instance, focused on social relations, good conduct, and human society. By contrast, Taoism took a more mystical approach, and focused on the individual and nature.

Other important features of Taoism were its anti-authoritarian stance, its promotion of simplicity, and its recognition of a natural, universal force known as the Tao . Whilst it may be said that Confucianism better suited the tastes of China’s rulers, Taoism was nevertheless a highly influential force, and remains so in Chinese culture even today.

Featured image: An Illustration of Lao-Tzu. Photo source: ( patriziasoliani /CC BY-NC 2.0 ).

Chan, A., 2013. Laozi. [Online] Available at: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/laozi/

Littlejohn, R., 2016. Daoist Philosophy. [Online] Available at: http://www.iep.utm.edu/daoism/

Littlejohn, R., 2016. Laozi (Lao-tzu, fl. 6th cn. B.C.E.). [Online] Available at: http://www.iep.utm.edu/laozi/

Majka, C., 2016. Lao Tzu: Father of Taoism. [Online] Available at: http://www.chebucto.ns.ca/Philosophy/Taichi/lao.html

Lao Tzu's full story can be found in the Urantia revelation

Wu Mingren (‘Dhwty’) has a Bachelor of Arts in Ancient History and Archaeology. Although his primary interest is in the ancient civilizations of the Near East, he is also interested in other geographical regions, as well as other time periods.... Read More

Related Articles on Ancient-Origins

Lao Tzu: the Tao of Reality.

A history of pantheism by Paul Harrison.

Are you a pantheist? Find out at the Scientific Pantheism site.

There is a thing, formless yet complete. Before heaven and earth it existed. We do not know its name, but we call it Tao. It is the Mystery of Mysteries.

The Tao te Ching is the oldest scripture of Taoism. It was composed during the warring states period when China descended into a chaos of rival kingdoms, some time between the sixth and the fourth or third centuries BC. It was supposedly written by Lao Tan, a possibly mythical figure, said to have lived till he was 160 or 200 years old.

The classical Chinese historian Ssuma Chien says the work was by Li Erh, a custodian of imperial archives from the state of Ch'u in southern China, in the present province of Honan. This was a fertile, well-watered state. "Its people make little exertion, delight in life, and neglect to store anything."

Li Erh was no seeker after fame. "The chief aim of his studies was how to keep himself concealed and remain unknown." says Ssuma Chien. Li Erh wrote his ideas only because, as he was heading into retirement, the royal gatekeeper pleaded with him to record his ideas before he disappeared into oblivion. He may have written the book under the pseudonym Lao Tan to avoid attention.

A brutally honest personal confession in the Tao te Ching [chapter 20] suggests that he was not always happy with his reclusive way of life and personality:

I alone am inert, showing no sign of desires, like an infant that has not yet smiled. Wearied, indeed, I seem to be without a home. The multitude all possess more than enough, I alone seem to have lost all … Common folks are indeed brilliant; I alone seem to be in the dark.

The book of Chuang Tzu pays tribute to his character: "Men all seek the first. He alone sought the last. He said: "Accept the world's refuse." Men all seek happiness. He alone sought completion in adaptation … He was always generous and tolerant towards things." [Chuang Tzu, chapter 33]

The Tao te Ching is a short, dense book of only 5,250 words - probably the most influential 5,250 words ever written. Its ideas became very popular under the Han dynasty in the second century BC.

Lao Tan/Li Erh was even said to have met Confucius. After one visit Confucius' disciples asked him how he was able to correct and admonish Lao Tzu. "In him I have seen the dragon that rides on the cloudy air," replied Confucius. "My mouth fell open and I was unable to shut it; how could I admonish and correct Lao Tan?" After another crushing visit he admitted: "In the knowledge of the Tao am I any better than a tiny creature in vinegar?" A final episode shows him becoming virtually a disciple of Lao Tzu.

These accounts are, of course, Taoist propaganda. In reality Confucius would have regarded Lao Tzu as a dangerous threat to established custom and filial piety. The Tao te Ching contains not a single word about either of these central Confucian concepts. Indeed by stressing spontaneity and harmony with nature, it represents a rebellion against Confucian obsession with form and duty.

But Taoism did alter the course of Confucianism, leading to the synthesis of neo-Confucianism in thinkers like Chang Tsai . It also moulded the shape of East Asian Buddhism, giving Buddhism a much less negative stance to the world.

Was Lao Tan/Li Erh a pantheist? His description of the reality of the Tao is of a mysterious, numinous unity underlying and sustaining all things. It is inaccessible to normal thought, language or perception. While he never calls the Tao a God, and rejects the idea that it is personal or concerned with humans, he clearly views it in the same light of awe and respect as believers view their Gods. Since the Tao is omnipresent and sustains everything, the Tao te Ching is clearly espousing a materialist form of pantheism.

The Tao te Ching does not fall into the trap of Buddhism, assuming that because there is an underlying unity the diversity of the world is an illusion and there is only "emptiness." It recognizes both being and non-being as complementary. Non-being defines being as dark outlines light. Being and diversity emanate from non-being.

Lao Tan/Li Erh also believed that human happiness consisted in understanding and living and acting in harmony with this underlying Reality. This means following a simple, frugal and peaceful way of life, not seeking after wealth, power or fame. Unlike the Chuang Tzu he is not an advocate of total withdrawal from public action. But he stresses the need for taking minimal action. He prefers non-violence over violence, softness over hardness, water over sharpened swords. He is a clear pre-cursor of both Jesus and Gandhi.

In government his philosophy makes him in certain ways Machiavellian and laissez-faire. Kings should not encourage learning, wisdom or virtue. They should fill their people's bellies and keep their minds empty. A happy country would be one where people could hear dogs barking in the next village, yet would have no desire to go there.

There are also repeated suggestions through the text that the sage can achieve long life and escape death. This gave rise to a much less philosophical aspect of later Taoism: the pursuit of everlasting life, not in heaven but on this earth, but through physical immortality, and by often magical means.

There are dozens of translations of the Tao te Ching, many of them radically different from one another. Unless otherwise indicated, the texts below are from Wing-Tsit Chan in A Sourcebook in Chinese Philosophy , Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1969. Additional biographical material from Fung-Yu Lan, A History of Chinese Philosophy , trs Derk Bodde, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1952, and James Legge, The Texts of Taoism , Sacred Books of the East vol 40, Dover, New York, 1962.

Selected passages.

Nature of the tao, origin of all things..

There is a thing, formless yet complete. Before heaven and earth it existed. Without sound, without substance, it stands alone and unchanging. It is all-pervading and unfailing. One may think of it as the mother of all beneath Heaven. We do not know its name, but we call it Tao. 25. [Bodde]. Deep and still, it seems to have existed forever. 4.

Sustainer of all things.

The Great Tao flows everywhere. It may go left or right. All things depend on it for life, and it does not turn away from them. It accomplishes its tasks, but does not claim credit for it. It clothes and feeds all things, but does not claim to be master over them. Always without desires, it may be called the Small. All things come to it and it does not master them; it may be called The Great. 34.

Tao is incomprehensible to us by normal means or language.

We look at it and do not see it; Its name is the invisible. We listen to it and do not hear it; Its name is the inaudible. We touch it and do not find it; Its name is the Subtle (formless). These three cannot be further probed, and hence merge into one … Infinite and boundless, it cannot be given any name; It reverts to nothingness. This is called shape without shape, form without object. It is the vague and elusive. Meet it and you will not see its head. Follow it and you will not see its back. 14. The Tao that can be told of is not the eternal Tao; the name that can be named is not the eternal name. 1.

Tao is both being and non-being.

Non-Being is the term given to that from which Heaven and Earth sprang. Being is the term given to the mother that rears all things … [Bodde] The two are the same, But after they are produced , they have different names. The two together we call the Mystery. It is the Mystery of Mysteries. [Bodde]. 1.

Being and Non-being produce each other.

When the people of the world all know beauty as beauty, There arises the recognition of ugliness. When they know the good as the good, There arises the perception of evil. Therefore Being and non-Being produce each other. 2. The thing that is called Tao is eluding and vague. Vague and eluding, there is in it form. Eluding and vague, in it are things. 21.

Tao achieves action through inaction.

Tao invariably takes no action, and yet there is nothing left undone. 37. Clay is molded to form a vessel, But it is on its non-being that the usefulness of the utensil depends. Doors and windows are cut to make a room, but it is on its non-being that the utility of the room depends. 11.

Tao is indifferent to human affairs.

Heaven and earth are not humane. They regard all things as straw dogs. 5.

Following the Tao in human affairs

Success in human affairs depends on understanding and following the nature of the tao..

Hold on to the Tao of old in order to master the things of the present. 14. Being one with Nature, he is in accord with the Tao. Being in accord with the Tao, he is everlasting. 16.

Avoid action.

The sage manages affairs without action And spreads doctrines without words … By acting without action, all things will be in order. 3.

Be content with enough; don't go too far.

To hold and fill to overflowing is not as good as to stop in time. Sharpen a sword-edge to its very sharpest, And the edge will not last long … Withdraw as soon as your work is done. Such is Heaven's Way. 9.

Softness conquers: non-violence.

The weak and the tender overcome the hard and the strong. 36. To yield is to be preserved whole. To be bent is to become straight. To be empty is to be full … To have little is to possess. 22. The stiff and the hard are companions of death, The tender and the weak are companions of life. 76. There is nothing softer and weaker than water, And yet there is nothing better for attacking hard and strong things. 78. The use of force usually brings requital. Wherever armies are stationed, briers and thorns grow. Great wars are always followed by famines. 30. Weapons are instruments of evil, not the instruments of a good ruler. When he uses them unavoidably, he regards calm restraint as the best principle. Even when he is victorious, he does not regard it as praiseworthy, For to praise victory is to delight in the slaughter of men. 31.

Turn the other cheek.

I treat those who are good with goodness, And I also treat those who are not good with goodness, Thus goodness is attained. 49. Whether it is big or small, many or few, repay hatred with virtue. 63.

Return to the root.

Attain complete emptiness, Maintain steadfast quietude. All things flourish But each one returns to its root. This return to its root means tranquility. 16.

Pursue simplicity and frugality.

Therefore let people hold on to these: Manifest plainness, Embrace simplicity, Reduce selfishness, Have few desires. 19. He who hoards most will lose heavily, He who is contented suffers no disgrace. 44.

Avoid overconsumption.

There is no calamity greater than lavish desires. There is no greater guilt than discontentment. And there is no greater disaster than greed. He who is contented with contentment is always contented. The courts are exceedingly splendid, while the fields are exceedingly weedy, and the granaries are exceedingly empty. Elegant clothes are worn, sharp weapons are carried, Foods and drinks are enjoyed beyond limit, And wealth and treasures are accumulated in excess. This is robbery and extravagance. This is indeed not the Tao. 53.

ARE YOU A TAOIST, OR A PANTHEIST, OR BOTH?

Philosophical Taoism overlaps in many respects with Scientific Pantheism. Both are non-dualist, and deny that spirit and matter are separate substances. Both are non-theist, and deny the existence of any personal creator God or supernatural realm. Yet both have a deeply religious reverence for nature and the universe. Both stress the importance of living in harmony with nature. If you are attracted to the Taoism of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu, then you will find scientific pantheism totally congenial. There are of course some differences. Unlike Chuang Tzu, Scientific Pantheism does not advocate social inaction, and does not assume that there is an ultimate reality beyond the material universe (though it does not deny the possibility of this). Scientific Pantheism is completely free of the later accretions of religious Taoism: the alchemical pursuit of physical immortality, the multiplicity of deities and so on. Scientific Pantheism recognizes the right of all pantheists to celebrate their beliefs in any ritual or symbolic form they prefer: so it is entirely possible to be a scientific pantheist and a Taoist at the same time, and many of our members are. If you would like to spread the message of scientific pantheism please include a link to Scientific pantheism in your pages, and make sure yours are indexed in the main Web engines and directories. Use the word pantheist whenever possible. Check How you can help for more details. Elements of Pantheism , An overview of pantheist history, theory and practice. Includes almanac and calendar. $9.95 US - ©5.99 UK 20% off at Amazon Books The Finest of Religion, Science, Nature and Philosophy Bookstore Come have arabica coffee and browse with Lao Tzu, Einstein, Thoreau, Spinoza, Sagan, Wordsworth, Whitman, Hawking, Marcus Aurelius, and friends.

- Member Benefits

- T-shirts, mugs, gifts

- Posters, Stickers, T-shirts

- Printable Cards

- WPM Statement of principles

- Elements of Pantheism paperback

- Elements of Pantheism Kindle

- Beliefs of Naturalistic Pantheism

- Pantheism as a way of life

- History of Pantheism

- A Pantheist Glossary

- Take our top-rated quiz

- Agnosticism and Pantheism

- Atheism and Pantheism

- Earth Religions and Pantheism

- Naturalism and Pantheism

- Paganism and Pantheism

- Unitarian Universalism and Pantheism

- Members' voices

- Books on Pantheism

- Save Nature

- Greenup Your Life

- Natural Death

- Pantheism and Rights

- Religious Freedom

- Evolution Education

- Natural Meditation

- Pantheist Calendar

- Pantheist Almanac

- Pantheist Art

- Facebook Page

- Facebook discussion group

- Social network

- Local groups network

- Map of local groups

- Find Pantheists Near You [Members Only]

- Practical living

- Stages of Life

- Environment & Nature

- Causes and Issues

- Interests & Activities

- Start a group

- Unitarian Universalist groups

- Why organize?

- Certificate of Incorporation

- Certificate of Good Standing

- Charity Status

- US Tax Status

- US Definitive Ruling

- 2004-5 Accounts

- 2006-11 Accounts

- Renew/Update

- Find members near you

- Access & password issues

- Online guide to resources

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Confucianism, Daoism (Taoism), and Buddhism generally name the three main currents of Chinese thought, although it should be obvious that like any “ism,” they are abstractions—what they name are not monolithic but multifaceted traditions with fuzzy boundaries. In the case of “Daoism,” it designates both a philosophical tradition and an organized religion, which in modern Chinese are identified separately as daojia and daojiao , respectively. With their own rich histories and internal differences, the two are deeply intertwined. Laozi (or Lao-tzu, in the “Wade-Giles” system of transliteration favored by earlier generations of Western scholars) figures centrally in both.

Philosophical Daoism traces its origins to Laozi, an extraordinary thinker who flourished during the sixth century B.C.E., according to Chinese sources. According to some modern scholars, however, Laozi is entirely legendary; there was never a historical Laozi. In religious Daoism, Laozi is revered as a supreme deity.

The name “Laozi” is best taken to mean “Old ( lao ) Master ( zi ),” and Laozi the ancient philosopher is said to have written a short book, which has come to be called simply the Laozi , after its putative author, a common practice in early China.

When the Laozi was recognized as a “classic” ( jing )—that is, accorded canonical status in the classification of Chinese literature, on account of its profound insight and significance—it acquired a more exalted and hermeneutically instructive title, Daodejing ( Tao-te ching ), commonly translated as the “Classic of the Way and Virtue.” Its influence on Chinese culture is pervasive, and it reaches beyond China. It is concerned with the Dao or “Way” and how it finds expression in “virtue” ( de ), especially through what the text calls “naturalness” ( ziran ) and “nonaction” ( wuwei ). These concepts, however, are open to interpretation. While some interpreters see them as evidence that the Laozi is a deeply spiritual work, others emphasize their contribution to ethics and/or political philosophy. Interpreting the Laozi demands careful hermeneutic reconstruction, which requires both analytic rigor and an informed historical imagination.

1. The Laozi Story

2. date and authorship of the laozi, 3. textual traditions, 4. commentaries, 5. approaches to the laozi, 6. dao and virtue, 7. naturalness and nonaction, other internet resources, related entries.

The Shiji (Records of the Historian) by the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.) court scribe and historian Sima Qian (ca. 145–86 B.C.E.) offers a “biography” of Laozi. Its reliability has been questioned, but it provides a point of departure for reconstructing the Laozi story.

Laozi was a native of Chu, according to the Shiji , a southern state in the Zhou dynasty (see map and discussion in Loewe and Shaughnessy 1999, 594 and 597). His surname was Li; his given name was Er, and he was also called Dan.

Laozi served as a keeper of archival records at the court of Zhou. Confucius (551–479 B.C.E.) had consulted him on certain ritual matters, we are told, and praised him lavishly afterward ( Shiji 63). This establishes the traditional claim that Laozi was a senior contemporary of Confucius. A meeting, or meetings, between Confucius and Laozi, identified as “Lao Dan,” is reported also in the Zhuangzi and other early Chinese sources.

“Laozi cultivated Dao and virtue,” as Sima Qian goes on to relate, and “his learning was devoted to self-effacement and not having fame. He lived in Zhou for a long time; witnessing the decline of Zhou, he departed.” When he reached the northwest border then separating China from the outside world, he met Yin Xi, the official in charge of the border crossing, who asked him to put his teachings into writing. The result was a book consisting of some five thousand Chinese characters, divided into two parts, which discusses “the meaning of Dao and virtue.” Thereafter, Laozi left; no one knew where he had gone. This completes the main part of Sima Qian’s account. The remainder puts on record attempts to identify the legendary Laozi with certain known historical individuals and concludes with a list of Laozi’s purported descendants (see W. T. Chan 1963, Lau 1963, or Henricks 2000 for an English translation).