- Cast & crew

- User reviews

Star Trek: The Motion Picture

When an alien spacecraft of enormous power is spotted approaching Earth, Admiral James T. Kirk resumes command of the overhauled USS Enterprise in order to intercept it. When an alien spacecraft of enormous power is spotted approaching Earth, Admiral James T. Kirk resumes command of the overhauled USS Enterprise in order to intercept it. When an alien spacecraft of enormous power is spotted approaching Earth, Admiral James T. Kirk resumes command of the overhauled USS Enterprise in order to intercept it.

- Robert Wise

- Gene Roddenberry

- Harold Livingston

- Alan Dean Foster

- William Shatner

- Leonard Nimoy

- DeForest Kelley

- 582 User reviews

- 121 Critic reviews

- 50 Metascore

- 4 wins & 21 nominations total

- Captain Kirk

- Janice Rand

- Klingon Captain

- Epsilon Technician

- Airlock Technician

- Commander Branch

- Assistant to Rand

- (as John D. Gowans)

- Cargo Deck Ensign

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Did you know

- Trivia When Captain Kirk addresses the crew before launching, many of the extras were noted Star Trek fans, including Bjo Trimble , co-organizer of the letter-writing campaign that kept Star Trek (1966) alive for a third season.

- Goofs When Kirk first comes on board Enterprise he is called "Admiral," and then "Captain" a few seconds later. However, it is customary for the person in command of a ship to be addressed as "Captain," regardless of his military rank.

[last lines]

Chief DiFalco : Heading, sir?

Captain James T. Kirk : Out there... thataway.

- Crazy credits End title: "The human adventure is just beginning."

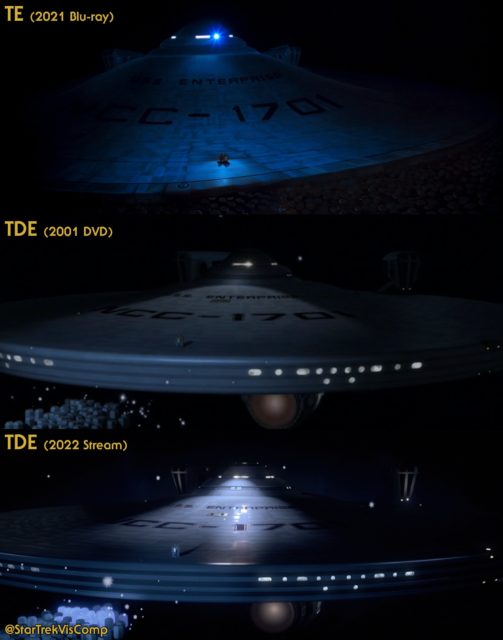

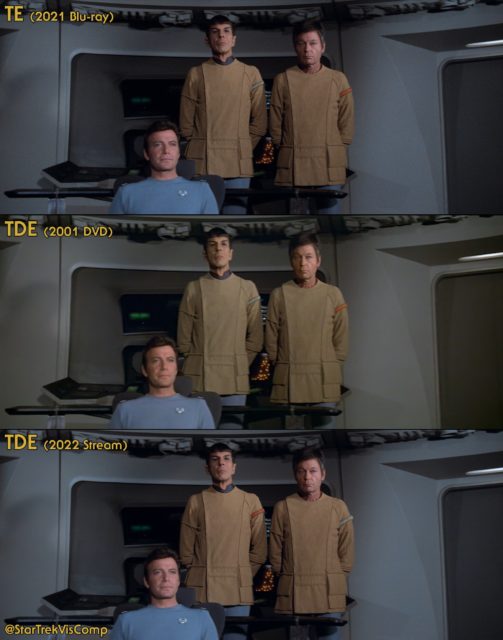

- The landscape of Vulcan was changed to include a yellowish sky and new landscape featuring massive statues. All other footage was tinted gold.

- The matte painting of the Golden Gate Bridge in the scene where Kirk arrives at Starfleet Headquarters was replaced by a new CGI scene that shows Kirk's shuttle arriving at Starfleet. It is actually slightly longer than the original version.

- The matte painting of Starfleet Command was improved with CGI effects, including an original series shuttle launched in the background.

- In a close-up shot when Kirk first sees the new Enterprise from his shuttle, the image of the ship was superimposed over Kirk's face as a reflection in the shuttle's window.

- After Kirk leaves the bridge, a short conversation between Sulu, Uhura and an alien officer was inserted.**

- A new CGI shot of the Earth is shown on the viewscreen when the Enterprise leaves the planet.

- A new CGI effect showing one of the Enterprise's nacelles was inserted into the window when Kirk, Spock and McCoy speak on the observation deck.

- A new CGI shot was inserted which shows V'Ger's second energy torpedo vanishing before it could strike the Enterprise.

- The energy probe that invades the bridge now approaches in a CGI exterior shot.

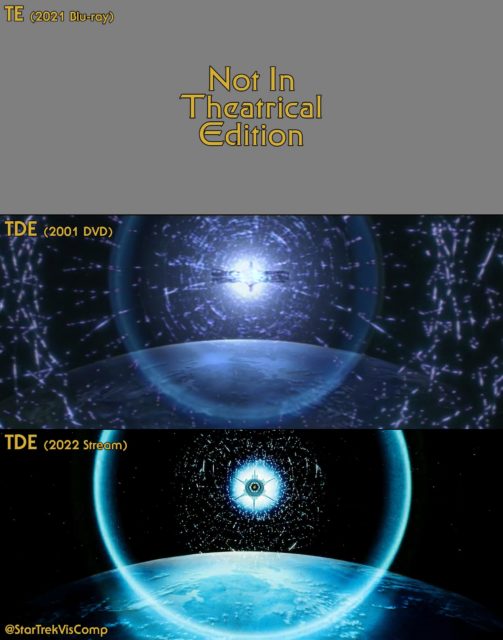

- A new CGI shot shows the V'Ger vessel entering Earth orbit.

- The scene in which Chekov burns his hand is much longer and shows Lt. Ilia healing him with her empathic powers instead of Nurse Chapel.**

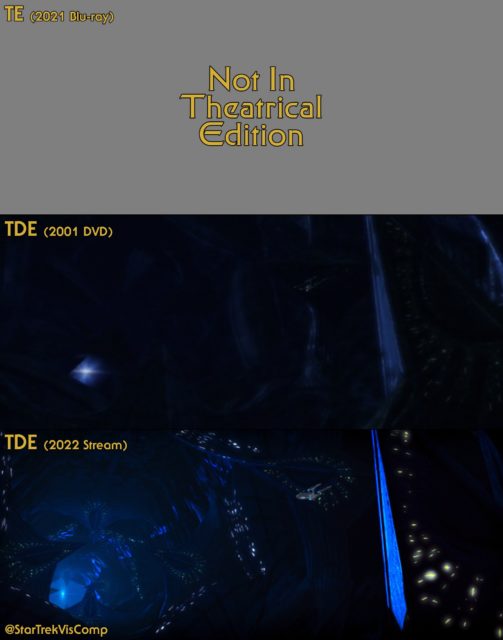

- The long walk to V'Ger was totally redone. There is now a walkway that materializes out of thin air, compared to the endless field in the original version.

- The Enterprise's voyage to the center of V'Ger is slightly extended. It has a scene of Spock sharing a tear "for V'Ger" and Scotty ordered to self-destruct the ship if the landing party is unsuccessful.**

- The small black "empty matte" in the window when Decker and Ilia confront each other in the recreation deck was replaced with a CGI shot of the V'Ger cloud interior.

- The final explosion of V'Ger was slightly extended. The shot from the original version remained intact, but a new element of the vessel imploding its energy for the explosion was added.

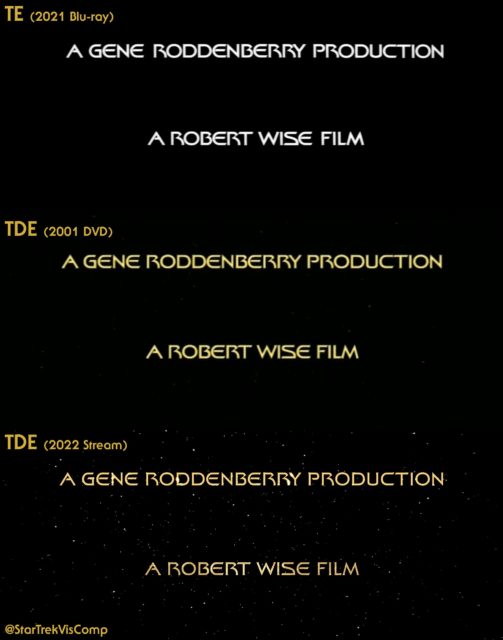

- New opening titles were commissioned for the film's opening. The opening titles now have a slight fading effect and are now seen over a background of stars. The text is colored a bright gold, compared to the original version's white.

- The explosion in the wormhole was redone. There is now an exterior shot of the asteroid exploding and the wormhole disintegrating. Additionally, the viewfinder in the next shot is enhanced to show sparks and debris.

- The final message to the audience, "The human adventure is just beginning", was altered. In the original version, the starfield cuts away to a blank title card showing the text. In the Director's Edition, the starfield was extended by a few seconds to allow the text, colored bright gold, to fade into the picture.

- The ending credits were slightly altered. The text, as with the opening titles and the final "human adventure" text, was changed color, from white to a bright gold. Additionally, the music was slightly extended to add new Director's Edition credits.

- An all-new sound mix was commissioned, keeping the music and dialog intact, and adding new effects for almost all scenes. For example, the Enterprise computer voice alarms are now replaced with klaxon sirens, the lightning effects have new echoes, and a blend of Enterprise bridge sound effects from the original Star Trek series, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, and Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country have been added into the background of scenes taking place on the bridge. The new mix is in Dolby 5.1 EX Surround.

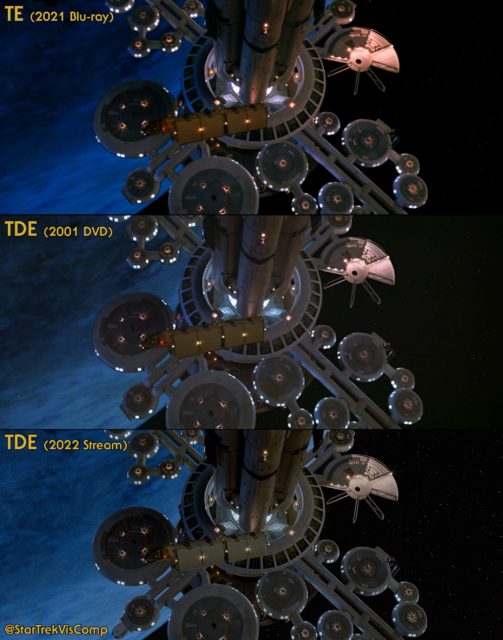

- The footage from 1979 was digitally restored and remastered, and combined with the new CGI elements.

- The opening overture has been restored to its full length. It is also played over a CGI starfield, rather than the blank screen in the original version.

- A slight dialog alteration was made: In the 1979 and 1983 versions, the V'Ger cloud is said to be "over 82 AUs in diameter" which equals 7.626 billion miles across - much too large for the Enterprise to realistically travel to the heart of the cloud at subwarp speeds within a reasonable length of time. For the Director's Edition, the Epsilon 9 commander's dialog was altered so that the cloud is now said to be a (somewhat) more reasonable "over 2 AUs", or 186 million miles.

- The producers of the Director's Edition submitted the film for re-rating by the MPAA, hoping for a PG rating rather than the original G rating which they believed carried a negative association; the basis for the higher rating was the intensified soundtrack. Oddly, when the original theatrical version was released on DVD and Blu-ray in 2009, it carried no MPAA rating.

- Scenes previously available in the "special longer version."

- Connections Edited into Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

- Soundtracks Theme from 'Star Trek: The television Series' Written by Alexander Courage and Gene Roddenberry

User reviews 582

- MC1-Bjornson

- May 24, 2007

- How long is Star Trek: The Motion Picture? Powered by Alexa

- Why did V'Ger choose to take Ilia out of all the people on the Enterprise?

- Did V'Ger ever transmit its data or just join with the Creator?

- What is "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" about?

- December 8, 1979 (United States)

- United States

- Startrek.com

- Star Trek I: The Motion Picture

- Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, USA (portions of planet Vulcan sequence filmed at Minerva Terrace)

- Paramount Pictures

- Century Associates

- Robert Wise Productions

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- $35,000,000 (estimated)

- $82,604,699

- $11,926,421

- Dec 9, 1979

- $82,676,805

Technical specs

- Runtime 2 hours 23 minutes

- Dolby Stereo

- Dolby Surround 7.1

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

Star Trek: The Motion Picture

" The Human adventure is just beginning... "

" Ten years ago, a television phenomenon became a part of life, shared in 47 different languages, read in 469 publications, and seen by 1.2 billion people. A common experience remembered around the world. Now Paramount Pictures brings the memory to life. "

After an eighteen-month refit process, the USS Enterprise is ready to explore the galaxy once again. But when a huge, invincible cloud approaches Earth , Admiral James T. Kirk must assume command of his old ship in order to stop it. Crew members old and new face new challenges, and must work together to triumph over the unknown.

- 1.1 Act One

- 1.2 Act Two

- 1.3 Act Three

- 2 Log entries

- 3 Memorable quotes

- 4.2 Costs and revenues

- 4.3.1 Robert Abel & Associates

- 4.3.2 Future General Corporation and Apogee

- 4.4.1 Alien languages

- 4.4.3 Make-up

- 4.4.4 Voyager aka V'ger

- 4.4.5 Saucer separation

- 4.4.6 The walk to V'ger

- 4.5.1 Late 1967 – June 1976: Early revitalization attempts

- 4.5.2 July 1976 – May 1977: Star Trek: Planet of the Titans

- 4.5.3 May 1977 – November 1977: Star Trek: Phase II

- 4.5.4 December 1977 – December 1979: Star Trek: The Motion Picture

- 4.5.5 1980s releases and merchandising

- 4.5.6 1990s merchandising

- 4.5.7 2000s and beyond merchandising

- 4.6.1 Awards and honors

- 4.7 Apocrypha

- 5.1.1 Opening credits

- 5.1.2.1.1 All Rights Reserved.

- 5.1.3 Star Trek: The Motion Picture (The Director's Edition)

- 5.1.4 Uncredited co-stars

- 5.1.5 Uncredited stunt performers

- 5.1.6 Uncredited production staff

- 5.1.7 Uncredited production companies

- 5.2.1 Spacecraft references

- 5.3 Script references

- 5.4 Other references

- 5.5 Further reading

- 5.6 External links

Summary [ ]

Act one [ ].

Amar firing a photon torpedo at an unknown cloud

In Klingon space, three Klingon K't'inga -class battle cruisers approach a massive cloud-like anomaly. As they approach it, the captain of one of the ships, the IKS Amar , orders photon torpedoes . They're armed and targeted on the center of the cloud, and the captain orders them to fire. The torpedoes are launched, and streak toward the anomaly. However, they abruptly disappear on sensors ; the captain orders evasive maneuvers, and the vessels pull back. Meanwhile, in Federation space, a listening post, Epsilon IX , picks up a distress signal from one of the Klingon ships. Commander Branch asks what they're fighting, and a lieutenant responds that she doesn't know. Another officer reports he has a visual, and the ships continue away from the cloud. A plasma-energy weapon streaks from the cloud hits one of the ships, engulfing it in plasma bolts before seemingly fading out of existence. On a tactical display on the Amar, the captain sees they're the only ship in that area. Another plasma weapon is launched, and the captain orders aft torpedoes fired. As the plasma weapon approaches, a torpedo is fired from the rear launcher, but disappears on contact with the plasma weapon. With nothing they can do, the weapon hits the Amar, engulfing it in plasma bolts, before it, too, disappears. On Epsilon IX, the lieutenant reports the cloud will pass by them, and it's on a direct course for Earth.

" You have not achieved kolinahr . "

On the planet Vulcan , Spock has been undergoing the kolinahr ritual, in which he has been learning how to purge all of his remaining emotions, and is nearly finished with his training. The lead elder tells Spock of how their ancestors had long ago cast out all animal passions on those sands, and says that their race was saved by attaining kolinahr , which another elder describes as the final purging of all emotion. The lead elder tells Spock he has labored long and she prepares to give him a symbol of total logic . She is about to give him a necklace , when Spock reaches out and stops her, clearly disturbed by something out in space. She asks for a mind meld to read his thoughts, to which Spock complies. She discovers that the alien intelligence which has called to him from deep space has stirred his Human half. She drops the necklace and states, " You have not yet achieved kolinahr . " She then tells the other elders, " His answer lies elsewhere. He will not achieve his goal with us. " Then she bids him farewell, telling him to " live long and prosper ." Spock picks up the necklace from the ground and holds it in his hand.

Meanwhile, at the Presidio campus of Starfleet Headquarters in San Francisco , Admiral James T. Kirk arrives in air tram 3 . As he steps out, he sees Commander Sonak , a Vulcan science officer who is joining the Enterprise crew and was recommended for the position by Kirk himself. Kirk is bothered as to why Sonak is not on board yet. Sonak explains that Captain Decker , the new captain of the USS Enterprise , wanted him to complete his science briefing at Starfleet Headquarters before departing. The Enterprise has been undergoing a complete refitting for the past eighteen months and is now under final preparations to leave drydock , which will take at least twenty hours, but Kirk informs him that they only have twelve. He tells Sonak to report to him on the Enterprise in one hour – he has a short meeting with Admiral Nogura and is intent on being on the Enterprise at that time.

Following the meeting, Kirk transports to an orbital office complex of the San Francisco Fleet Yards and meets Montgomery Scott , chief engineer of the Enterprise . Scott expresses his concern about the tight departure time. After the two men enter a travel pod and the doors seal shut, Kirk explains that an alien object is less than three days away from Earth, and the Enterprise has been ordered to intercept it because they are the only ship in range. Scott says that the refit, a process that took eighteen months, can't be finished in twelve hours and tries to convince him that the ship needs more work done as well as a proper shakedown . Kirk firmly insists that they are leaving, ready or not, in twelve hours. Scott activates the travel pod's thrusters and they begin the journey over to the drydock in orbit that houses the Enterprise .

" They gave her back to me, Scotty. "

Scott tells Kirk that the crew hasn't had near enough transition time with all the new equipment and that the engines haven't even been tested at warp power, not to mention that they have an untried captain in command. Kirk tells Scott that two and a half years as the Chief of Starfleet Operations may have made him a little stale, but that he wouldn't exactly consider himself untried. Kirk then tells a surprised Scott that Starfleet has given him back his command of the Enterprise . Scott comments that he doubts it was so easy with Admiral Nogura, and Kirk tells him he's right. While sharing a laugh with Kirk, Scott remarks, " Any man who can manage such a feat I wouldna dare disappoint. She'll launch on time, sir... and she'll be ready, " and gently puts his hand on the admiral's arm. They arrive at the Enterprise held in drydock , and Scott gives Kirk a brief tour of the new exterior of the ship.

A transport goes bad

Upon docking with the ship and entering the Enterprise 's cargo bay , Scott is immediately called to engineering. Kirk takes a turbolift up to the bridge, and upon arrival, is informed by Lieutenant Commander Uhura that Starfleet has just transferred command from Captain Decker over to him, and she, along with several other crewmembers including Sulu and Chekov , step forward excitedly to greet Kirk, who appreciates the welcome but wishes it were under more pleasant circumstances. Kirk asks the crew where Decker is. " He's in, uh, engineering, sir. He, uh... he doesn't know, " Sulu says. Kirk makes his way to the new engine room and pauses to look at Enterprise 's warp core before taking the lift down to where Captain Decker is busy assisting Scott with launch preparations. After Kirk takes him aside to talk, he becomes visibly upset when the admiral tells him that he is assuming command. Decker will remain on the ship as executive officer and will receive a temporary demotion to commander. As Decker storms off, an alarm sounds. Someone is trying to beam over to the ship, but the transporter is malfunctioning. Cleary informs Scott that there is a red line on the transporter. Kirk and Scott promptly race over to the transporter room . Transporter chief Janice Rand is frantically trying to tell Starfleet to abort the transport, but it is too late. Commander Sonak and a female officer are beaming in, but their bodies aren't re-forming properly in the transporter beam . The female officer screams horrifically, and then their bodies disappear. Starfleet tells them that they have died. With tears beginning to form in his eyes , Kirk tells Starfleet to express his sympathies to their families. He mentions that Sonak's can be reached through the Vulcan embassy . " There was nothing you could have done, Rand, " Kirk tells the upset transporter operator, " it wasn't your fault. "

In the corridor outside the transporter room, Kirk sees Decker and tells him they will have to replace Commander Sonak. Kirk wants another Vulcan if possible. Decker tells him that no one is available that is familiar with the ship's new design. Kirk tells Decker he will have to double his duties as science officer as well.

Kirk addresses the Enterprise crew

In the Enterprise 's recreation room , as Kirk briefs the assembled crew on the mission, they receive a transmission from Epsilon IX. Commander Branch tells them they have analyzed the mysterious cloud. It generates an immense amount of energy and measures 82 au ( only 2 au in the director's edition ) in diameter. Branch also reports that there is a vessel of some kind in the center. They've tried to communicate with it, but there has been no response. The lieutenant reports that further scans indicate something inside the cloud, but all scans get reflected back. Suddenly, an alarm goes off on the station, and Branch reports they're under attack. Kirk orders an external view of the station, and plasma bolts start engulfing it. The crew is watching this happen, and Epsilon IX disappears. Ordering Uhura to deactivate the viewer, Kirk informs the crew that the pre-launch countdown will begin in forty minutes and the assembled crew leaves to attend to their duties.

Epsilon IX destroyed

Act Two [ ]

Lieutenant Ilia steps on the bridge

Later on the bridge, Uhura informs Kirk that the transporter has been fully repaired and is functioning properly now. Lieutenant Ilia , the Enterprise 's Deltan navigator , arrives. Decker is happy to see her, as they developed a romantic relationship when he was assigned to her home planet several years earlier. Ilia is curious about Decker's reduction in rank and Kirk interrupts and tells her about Decker being the executive and science officer. Decker tells her, with slight sarcasm, that Captain Kirk has the utmost confidence in him. Ilia tells Kirk that her oath of celibacy is on record and asks permission to assume her duties. Uhura tells Kirk that one of the last six crew members to arrive is refusing to beam up. Kirk goes to the transporter room to ensure that the person is beamed up.

Dr. McCoy beams aboard

When told by a yeoman that the crew member insisted on them beaming up first, " said something about first "seeing how it scrambled our molecules ," " Kirk tells Starfleet to beam the officer aboard. Dr. McCoy , dressed in civilian attire and wearing a thick beard , materializes on the transporter platform. McCoy is angry that his Starfleet commission was reactivated . He realizes that Kirk is responsible for the draft. His attitude changes, however, when Kirk says he desperately needs him. McCoy leaves to check out the new sickbay , grumbling about all the new changes to the Enterprise .

The crew finishes its repairs and the Enterprise leaves drydock and heads into the solar system at impulse .

The Enterprise in a wormhole.

A clean-shaven Dr. McCoy arrives on the bridge and complains that the new sickbay is now nothing but a " damned computer center. " Kirk is anxious to intercept the cloud intruder at the earliest possible opportunity, and despite protests from Scott and Decker, he orders warp drive engaged. The Enterprise goes to warp 1 successfully, and Kirk turns to speak with Decker, but an alarm draws his attention to the viewscreen. The Enterprise has entered a wormhole , and Kirk orders full reverse. Uhura reports all communications are jammed, and Ilia reports an asteroid has been pulled into the wormhole and is on a collision course. Kirk orders phasers , but Decker countermands his order, goes over to the tactical station, and tells Chekov to arm photon torpedoes . Chekov is able to lock on to the asteroid, and Decker gives the order to fire. With four seconds left before impact, the torpedo leaves the launcher and collides with the asteroid, causing a massive explosion that rocks the Enterprise and causes the wormhole to dissipate. Sulu reports that helm control is restored, and Kirk, annoyed, wants Decker in his quarters. McCoy decides to come along, as well.

Once in Kirk's quarters, Kirk demands an explanation from Decker on why his phaser order was countermanded. Decker points out that the redesigned Enterprise now channels the phasers through the main engines and because they were imbalanced, the phasers were automatically cut off. Kirk acknowledges that he has saved the ship – however, he accuses Decker of competing with him. Decker, in his opinion, tells Kirk that, because of his unfamiliarity with the ship's new design, the mission is in serious jeopardy. Kirk sarcastically trusts that Decker will " nursemaid me through these difficulties, " and Decker tells the captain that he will gladly help him understand the new design. Kirk then dismisses him from the room. In the corridor, Decker runs into Ilia. Ilia asks if the confrontation was difficult, and he tells her that it was about as difficult as seeing her again, and apologizes. She asks if he is sorry for leaving Delta IV , or for not saying goodbye. He asks if, had he seen her again, would she have been able to say goodbye? She quietly says " no ," and goes to her quarters nearby.

Back in Kirk's quarters, McCoy accuses Kirk of being the one who is competing, and the fact that it was Kirk who used the emergency to pressure Starfleet into letting him regain command of the Enterprise . McCoy thinks that Kirk is obsessed with keeping his command. On Kirk's console viewscreen , Uhura informs Kirk that a Starfleet registered shuttlecraft is approaching and that the occupant wishes to dock. Chekov also pipes in and replies that it appears to be a courier vessel, non-belligerency confirmed. Kirk tells Chekov to handle the situation. Turning the viewer off, Kirk asks McCoy is he has anything more to add, to which McCoy quietly states " that depends on you, " and leaves Kirk to ponder this, while he stands silently.

Spock arrives aboard the Enterprise

The shuttle approaches the Enterprise from behind, and the top portion of it detaches and docks at an airlock just behind the bridge. Chekov is waiting by the airlock doors with a security officer and is surprised to see Spock come aboard. Moments later, Spock arrives on the bridge, and everyone is shocked and pleased to see him, yet Spock ignores them. He moves over to the science station and tells Kirk that he is aware of the crisis and knows about the ship's engine design difficulties.

" Well, so help me, I'm actually pleased to see you! "

He offers his services as the science officer. McCoy and Dr. Christine Chapel come to the bridge to greet Spock, but he only looks at them coldly and does not reply to them. Uhura tries to speak to Spock, but he ignores her as well and tells Kirk that with his permission, he will go to engineering and discuss his fuel equations with Scott. As Spock walks into the turbolift , Kirk stops him and welcomes him aboard. But Spock makes no reply and continues into the turbolift. Kirk and McCoy both share a look after Spock leaves the bridge.

With Spock's assistance, the engines are now rebalanced for full warp capacity. The ship successfully goes to warp to intercept the cloud. In the officers lounge, Spock meets with Kirk and McCoy. They discuss Spock's kolinahr training on Vulcan, and how Spock broke off from his training to join them. Spock describes how he sensed the consciousness of the intruder, from a source more powerful that he has ever encountered, with perfect, logical thought patterns. He believes that it holds the answers he seeks. Uhura tells Kirk over the intercom that they have made visual contact with the intruder.

With the entire ship on red alert, Kirk orders full mag on the viewer, and the massive cloud is revealed. The cloud scans the ship, but Kirk orders Spock not to return scans as they could be considered hostile. Spock determines that the scans are coming from the exact center of the cloud. Uhura reports that she's transmitting full friendship messages on all frequencies, but there is no response. Decker suggests raising the shields for protection, but Kirk determines that that might be considered hostile to the cloud. Spock analyzes the clouds composition and discovers it has a 12-power energy field, the equivalent of power generated by thousands of starships .

The Enterprise attacked

Sitting at the science station, Spock awakens from a brief trance. Kirk asks him what's happening, and Spock says the alien is puzzled. The Enterprise was contacted, so why is it not replying? Kirk asks Spock how they've been contacted, but an alarm coaxes him to his chair. A plasma-energy weapon has been launched toward the Enterprise, and Kirk orders full shields. The weapon hits, overloading multiple systems and sending bolts of plasma energy throughout the ship. Bolts of lightning surround the warp core and nearly injure several engineering officers. Chekov is injured – his hand badly burned from a plasma bolt emanating from the weapons station on the bridge. The bolt then finally disappears, and Scott reports deflector power is down seventy percent. A medical team is called to the bridge, and Ilia is able to use her telepathic powers to soothe Chekov's pain.

Spock confirms to Kirk that the alien has been attempting to communicate. It transmits at a frequency of more than one million megahertz, and at such a high rate of speed, the message only lasts a millisecond. Spock programs to computer to send linguacode messages at that frequency and rate of speed. Another plasma-energy weapon is launched, and Spock is still working as it approaches. With ten seconds left, Spock transmits the message. The weapon continues moving toward the Enterprise, but abruptly disappears right before it can collide. Kirk asks for recommendations, and Spock recommends proceeding inside the cloud to investigate, while Decker advises against it, calling the move an "unwarranted gamble." Kirk asks Decker what constitutes "unwarranted" to him, while Decker retorts that Kirk asked his opinion.

Enterprise encounters V'ger 's ship

Kirk orders that the ship continue on course through the cloud. They pass through many expansive and colorful cloud layers and upon clearing these, a giant vessel is revealed. Kirk asks for an evaluation and Spock reports that the vessel is generating a force field greater than the radiation of Earth's sun . Kirk tells Uhura to transmit an image of the alien to Starfleet, but she explains that any transmission sent out of the cloud is being reflected back to them. Kirk orders Sulu to fly above and along the top of the vessel at a distance of only five hundred meters.

As Enterprise moves in front of the alien vessel, Kirk orders to hold position. Suddenly, an alarm sounds, and another plasma weapon approaches the Enterprise. However, it slows down, stopping in front of the ship, and starts zapping the bridge. It forms a column in the bridge and the crew struggles to shield their eyes from its brilliant glow and their ears from the high-pitched shrieking buzz it lets out. Chekov asks Spock if it is one of the alien's crew, and Spock replies that it is a probe sent from the vessel. The probe slowly moves around the room and stops in front of the science station. Bolts of lightning shoot out from it and surround the console – it is trying to access the ship's computer. Kirk orders the computer turned off, which Decker tries to do, but it has taken control of it. Spock pulls Decker away and smashes the controls, which works. As he starts stepping away, he's suddenly given an electric shock by the probe and falls to the floor. The probe starts moving again, and approaches the navigation console. As Ilia is watching, it starts scanning her, much to Decker's horror. Spock tries to pull her away, but he's knocked back by an electric shock. Decker is similarly shocked to keep him away, and Ilia, horrified, stands there as she's scanned. As Decker's watching this, Ilia abruptly vanishes, and the tricorder she was holding falls to the floor. Kirk, shaken, picks up the tricorder. Decker angrily exclaims, "This is how I define unwarranted! "

Enterprise inside the ship

Another alert goes off, reporting helm control has been lost. Spock reports they've been caught by a tractor beam and Kirk orders someone up to take the navigator's station. Decker calls for Chief DiFalco to come up to the bridge as Ilia's replacement. Decker suggests that the ship fire phasers, but Spock, evocatively, asserts that " Any show of resistance would be futile, Captain. " The ship travels deep into the next chamber. Decker wonders why they were brought inside – they could have been easily destroyed outside. Spock deduces that the alien is curious about them. Uhura's monitor shows that the aperture is closing – they are now trapped inside. The ship is released from the tractor beam and suddenly, an intruder alert goes off. Someone has come aboard the ship and is in the crew quarters section.

Act Three [ ]

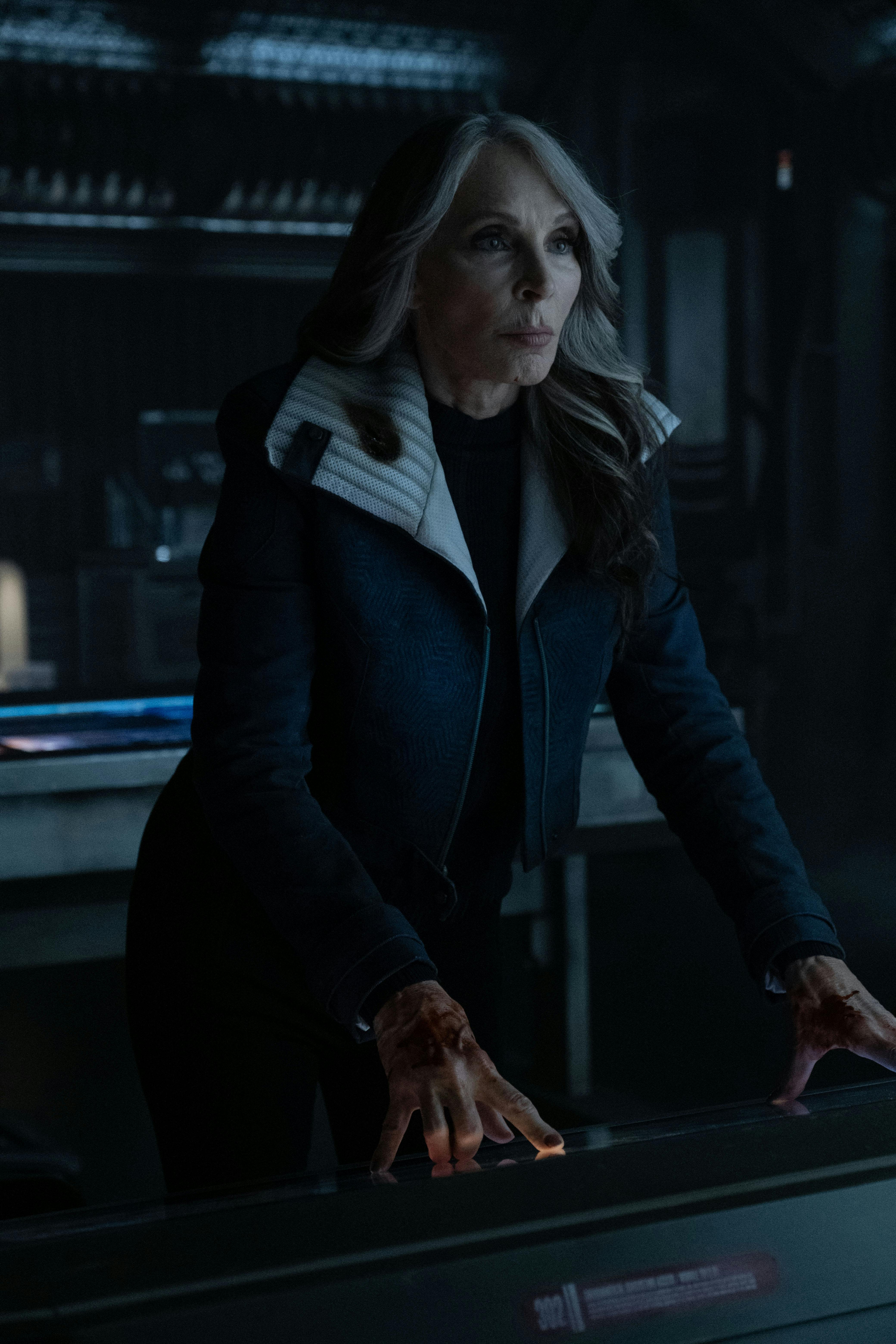

Ilia returns as V'ger 's probe

Kirk and Spock arrive inside a crewman's quarters to discover that the intruder is inside the sonic shower . It is revealed to be Ilia, although it isn't really her – there is a small red device attached to her neck . In a mechanized voice, she replies, " You are the Kirk unit, you will assist me. " She explains that she has been programmed by an entity called " V'ger " to observe and record the normal functions of the carbon-based units "infesting" the Enterprise . Kirk opens the shower door and " Ilia " steps out, wearing a small white garment that just materialized around her. Dr. McCoy and security officer Ensign Perez enter the room, and Kirk tells McCoy to scan her with a tricorder.

Kirk asks her who V'ger is. She replies, " V'ger is that which programmed me . " McCoy tells Kirk that Ilia is a mechanism and Spock confirms she is a probe that assumed Ilia's physical form. Kirk asks where the real Ilia is, and the probe states that "that unit" no longer functions. Kirk also asks why V'ger is traveling to Earth, and the probe answers that it wishes to find the Creator, join with him, and become one with it. Spock suggests that McCoy perform a complete examination of the probe.

"Ilia" being examined

" I am concerned with that being our only source of information, captain. "

In sickbay, the Ilia probe lays on a diagnostic table, its sensors slowly taking readings. All normal body functions, down to the microscopic level, are exactly duplicated by the probe, even eye moisture. Decker arrives and is stunned to see her there. She looks up at him and addresses him as " Decker ," rather than " Decker unit ," which intrigues Spock. Spock talks with Kirk and Decker in an adjoining room and Spock locks the door. Spock theorizes that the real Ilia's memories and feelings have been duplicated by the probe as well as her body. Decker is angry that the probe killed Ilia, but Kirk convinces him that their only contact with the vessel is through the probe, and they need to use that advantage to find out more about the alien. Suddenly, the probe bursts through the door, and demands that Kirk assist her with her observations. He tells her that Decker will do it with more efficiency. After Decker and the probe leave, Spock expresses concern to Kirk of that being their only source of information.

Decker and Ilia are seen walking around in the recreation room. He shows her pictures of previous ships that were named Enterprise . Decker is trying to see if Ilia's memories or emotions can resurface, but to no avail. Kirk and McCoy observe them covertly on a monitor from his quarters. Decker shows her a game that the crew enjoys playing. She is not interested and states that recreation and enjoyment have no meaning to her programming. At another game, which Ilia enjoyed and nearly always won, they both press one of their hands down onto a table to play it. The table lights up, indicating she won the game, and she gazes into Decker's eyes. This moment of emotion ends suddenly, and she returns to normal. " This device serves no purpose. "

" Why does the Enterprise require the presence of carbon units? ", she asks. Decker tells her the ship couldn't function without them. She tells him that more information is needed before the crew can be patterned for data storage. Horrified, he asks her what this means. " When my examination is complete, all carbon units will be reduced to data patterns. " He tells her that within her are the memory patterns of a certain carbon unit. He convinces her to let him help her revive those patterns so that she can understand their functions better. She allows him to proceed.

Meanwhile, in one of the ship's airlocks , Spock slips up behind the airlock technician and nerve pinches him into unconsciousness.

Decker, the probe, Dr. McCoy, and Dr. Chapel are in Ilia's quarters. Dr. Chapel gives the probe a decorative headband that Ilia used to wear. Chapel puts it over "Ilia's" head and turns her toward a mirror. Decker asks her if she remembers wearing it on Delta IV. The probe shows another moment of emotion, saying Dr. Chapel's name, and putting her hand on Decker's face, calling him Will. Behind them, McCoy reminds Decker that she is a mechanism. Decker asks "Ilia" to help them make contact with V'ger . She says that she can't, and Decker asks her who the Creator is. She says V'ger does not know. The probe becomes emotionless again and removes the headband.

Spock is now outside the ship in a space suit with an emergency evacuation thruster pack . He begins recording a log entry for Kirk detailing his attempt to contact the alien. He activates a panel on the suit and calculates thruster ignition and acceleration to coincide with the opening of an aperture ahead of him. He hopes to get a better view of the spacecraft interior.

" A thruster suit is reported missing. " " A thruster suit... that's Spock. Damn him! "

Kirk comes up to the bridge and Uhura tells him that Starfleet signals are growing stronger, indicating they are very close to Earth. Starfleet is monitoring the intruder and notifies Uhura that it is slowing down in its approach. Sulu confirms this and says that lunar beacons show the intruder is entering into Earth orbit . Chekov tells Kirk that airlock 4 has been opened and a thruster suit has been reported missing. Kirk figures out that Spock has done it, and orders Chekov to get Spock back on the ship. He changes his mind, and instead tells Chekov to determine his position.

Spock touches a button on his thruster panel and his thruster engine ignites. He is propelled forward rapidly, and enters the next chamber of the vessel just before the aperture closes behind him. The thruster engine shuts down, and the momentum carries Spock ahead further. He disconnects the thruster pack from his suit and it falls away from him.

Continuing his log entry, Spock sees an image of what he believes to be V'ger 's homeworld . He passes through a tunnel filled with crackling plasma energy, possibly a power source intended for a gigantic imaging system. Next, he sees several more images of planets , moons , stars , and galaxies all stored and recorded. Spock theorizes that this may be a visual representation of V'ger 's entire journey. " But who or what are we dealing with? ", he ponders.

Spock attempts mind meld with V'ger

He sees the Epsilon IX station, stored in every detail, and notes to Kirk that he is convinced that all of what he is seeing is V'ger , and that they are inside a living machine. Then he sees a giant image of Lt. Ilia with the sensor on her neck. Spock decides it must have some special meaning, so he attempts to mind meld with it. He is quickly overwhelmed by the multitude of images flooding his mind and falls back unconscious.

Spock in sickbay

Kirk is now in a space suit and has exited the ship. The aperture in front of the Enterprise opens, and Spock's unconscious body floats toward him. Later, Dr. Chapel and Dr. McCoy are examining Spock in sickbay. Dr. McCoy performs scans and determines that Spock endured massive neurological trauma from the mind meld. While he is telling Kirk this, they are interrupted by an incredible sound: Spock, regaining consciousness, is laughing softly, saying he should have known.

Spock describes V'ger as a sentient being, from a planet populated by living machines with unbelievable technology, allowing it access to a truly galactic store of knowledge. Yet for all of that, V'ger is barren, with no sense of mystery and no emotions to give meaning to its actions. Spock, seeing the irony when comparing V'Ger to himself, can not help but laugh: V'Ger has, for all intents and purposes, achieved Kolinahr – flawless logic and limitless knowledge – yet doing so has only made it see the gaps in its own understanding. Spock grasps Kirk's hand and tells him, "This simple feeling is beyond V'ger 's comprehension. No meaning, no hope. And Jim, no answers. It's asking questions. 'Is this all that I am? Is there nothing more?'"

Uhura chimes in and tells Kirk that they are getting a faint signal from Starfleet. The intruder has been on their monitors for a while and the cloud is rapidly dissipating as it approaches. Sulu also comments that the intruder has slowed to sub-warp speed and is only three minutes from Earth orbit. Kirk acknowledges and he, McCoy, and Spock go up to the bridge.

V'ger's ship enters low Earth orbit, and the cloud entirely disappears. Starfleet sends the Enterprise a tactical report on the intruder's position. Uhura tells Kirk that V'ger is transmitting a signal. Decker and "Ilia" come up to the bridge, and she says that V'ger is signaling the Creator. Spock determines that the transmission is a radio signal. Decker tells Kirk that V'ger expects an answer, but Kirk doesn't know the question. Then "Ilia" says that the Creator has not responded. Suddenly, a plasma weapon is launched and starts orbiting Earth. Chekov reports all planetary defense systems have gone offline. Several more plasma weapons are launched and all orbit Earth in unison.

McCoy notices that the bolts are the same ones that hit the ship earlier, and Spock says that these are hundreds of times more powerful, and from those positions, they can destroy all life on Earth. " Why? ", Kirk asks "Ilia." She says that the carbon unit infestation will be removed from the Creator's planet as they are interfering with the Creator's ability to respond and accuses the crew of infesting the Enterprise and interfering in the same manner. Kirk tells "Ilia" that carbon units are a natural function of the Creator's planet and they are living things, not infestations. However "Ilia" says they are not true lifeforms like the Creator. McCoy realizes V'ger must think its creator is a machine. Decker concurs, comparing it to "We all create God in our own image."

Spock compares V'ger to a child and suggests they treat it like one. McCoy retorts that this child is about to wipe out every living thing on Earth. To get "Ilia's" attention, Kirk says that the carbon units know why the Creator hasn't responded. The Ilia probe demands that Kirk " disclose the information ." Kirk won't do so until V'ger withdraws all the orbiting devices. In response to this, V'ger cuts off the ship's communications with Starfleet. She tells him again to disclose the information. He refuses, and a plasma energy attack shakes the ship. McCoy tells Spock that the child is having a " tantrum ."

Kirk tells the probe that if V'ger destroys the Enterprise , then the information it needs will also be destroyed with it. Ilia says that it is illogical to withhold the required information, and asks him why he won't disclose it. Kirk explains it is because V'ger is going to destroy all life on Earth. "Ilia" says that they have oppressed the Creator, and Kirk makes it clear he will not disclose anything. V'ger needs the information, says "Ilia." Kirk says that V'ger will have to withdraw all the orbiting devices. "Ilia" says that V'ger will comply, if the carbon units give the information.

Spock tells Kirk that V'ger must have a central brain complex. Kirk theorizes that the orbiting devices are controlled from there. Kirk tells "Ilia" that the information can't be disclosed to V'ger 's probe, but only to V'ger itself. "Ilia" stares at the viewscreen, and, in response, the aperture opens and drags the ship forward with a tractor beam into a massive tunnel. Chekov tells Kirk that the energy bolts will reach their final positions and activate in 27 minutes. Kirk calls to Scott on the intercom and tells him to stand by to execute Starfleet Order 2005 – the self-destruct command. A female crewmember, Ross , asks Scott why Kirk ordered self-destruct, and Scott tells her that Kirk hopes that when they explode, so will the intruder.

The countdown is now down to 18 minutes. DiFalco reports that they have traveled 17 kilometers inside the vessel. Kirk goes over to Spock's station and sees that Spock has been crying. " Not for us, " Kirk realizes. Spock tells him he is crying for V'ger , and that he weeps for V'ger as he would for a brother. As he was when he came aboard the Enterprise , so is V'ger now – empty, incomplete, and searching. Logic and knowledge are not enough. McCoy realizes Spock has found what he needed, but that V'ger hasn't. Decker wonders what V'ger would need to fulfil itself.

Spock comments that each one of us, at some point in our lives asks, " Why am I here?" "What was I meant to be? " V'ger hopes to touch its Creator and find those answers. DiFalco directs Kirk's attention to the viewscreen. They're approaching the next chamber, and see a light up ahead. Sulu reports that forward motion has stopped. Chekov replies that an oxygen / gravity envelope has formed outside of the ship. "Ilia" points to the structure on the screen and identifies it as V'ger . Uhura has located the source of the radio signal and it is straight ahead. "Ilia" says the carbon units will now provide the information, and a passageway slowly materializes from the light toward the Enterprise. Kirk chooses Spock and Bones to come, but Decker volunteers to go as well. They enter a turbolift as Uhura looks at the viewscreen.

The passageway

The passageway is reaching the Enterprise as they come up an airlock onto the hull. They start walking up the passageway, and at the end of the path is a concave structure, and in the center of it is an old NASA probe from three centuries earlier. Kirk rubs away the soot on the nameplate and makes out the letters "V G E R". He continues to rub and discovers that the craft is actually Voyager 6 . Kirk recalls the history of the Voyager program – it was designed to collect data and transmit it back to Earth. Decker tells Kirk that Voyager 6 disappeared through what was then called a black hole .

The heart of V'ger is revealed

Kirk says that it must have emerged on the far side of the galaxy and got caught in the machine planet's gravity. Spock theorizes that the planet's inhabitants found the probe to be one of their own kind – primitive, yet kindred. They discovered the probe's 20th century programming to collect data and return that information to its creator. The machines interpreted that instruction literally and constructed the entire vessel so that Voyager could fulfil its programming. Kirk continues by saying that on its journey back, it amassed so much knowledge that it gained its own consciousness .

"Ilia" tells Kirk that V'ger awaits the information. Kirk calls Uhura on his communicator and tells her to find information on the probe in the ship's computer , specifically the NASA code signal, which will allow the probe to transmit its data. Decker realizes that that is what the probe was signaling – it's ready to transmit everything. Kirk then says that there is no one on Earth who recognizes the old-style signal – so the Creator does not answer.

Kirk calls out to V'ger and says that they are the Creator. "Ilia" says that is not logical – carbon units are not true lifeforms. Kirk says they will prove it by allowing V'ger to complete its programming. Uhura calls Kirk on his communicator and tells him she has retrieved the code. Kirk tells her to set the Enterprise transmitter to the appropriate code frequency and to transmit the signal. Decker reads the numerical code on his tricorder and is about to read the final sequence, but V'ger burns out its own antenna leads to prevent reception.

"Ilia" says that the Creator must join with V'ger , and turns toward Decker. McCoy warns Kirk that they only have ten minutes left. Decker figures out that V'ger wanted to bring the Creator here and transmit the code in person. Spock tells Kirk that V'ger 's knowledge has reached the limits of the universe and it must evolve. Kirk says that V'ger needs a Human quality in order to evolve. Decker thinks that V'ger joining with the Creator will accomplish that. He then goes over to the damaged circuitry and fixes the wires so he can manually enter the rest of the code through the ground test computer. Kirk tries to stop him, but "Ilia" tosses him aside. Decker tells Kirk that he wants this as much as Kirk wanted the Enterprise .

V'ger evolves into a higher form of existence after merging with Decker

Suddenly, a bright light forms around Decker's body. "Ilia" moves over to him, and the light encompasses them both as they merge together. Their bodies disappear, and the light expands and begins to consume the area. Kirk, Spock, and McCoy retreat back to the Enterprise . The light starts engulfing V'ger's ship, and an enormous explosion of light forms in orbit. As the light clears, the Enterprise moves forward, unharmed. On the bridge, Kirk wonders if they have just seen the beginning of a new lifeform , and Spock says yes and that it is possibly the next step in their evolution. McCoy says that it's been a while since he's "delivered" a baby and hopes that they got this one off to a good start.

" Spock... did we just see the beginning of a new lifeform? " " Yes, captain. We witnessed a birth. "

Uhura tells Kirk that Starfleet is requesting the ship's damage and injury reports and vessel status. Kirk reports that there were only two casualties: Lieutenant Ilia and Captain Decker. He quickly corrects his statement and changes their status to "missing." Vessel status is fully operational. Scott comes on the bridge and agrees with Kirk that it's time to give the Enterprise a proper shakedown. When Scott offers to have Spock back on Vulcan in four days, Spock says that's unnecessary, as his task on Vulcan is completed.

Kirk orders the Enterprise out for more adventures

Kirk tells Sulu to proceed ahead at warp factor one. When DiFalco asks for a heading, Kirk simply says " Out there, that-away. "

With that, the Enterprise flies overhead and engages warp drive on its way to another mission of exploration and discovery.

Log entries [ ]

- Captain's log, USS Enterprise (NCC-1701), mid-2270s

Memorable quotes [ ]

" Heading? " " Sir, it's on a precise heading for Earth. "

" The Enterprise is in final preparation to leave dock. " " Which will require another twenty more hours at minimum, Admiral - " "Twelve."

" I'm on my way to a meeting with Admiral Nogura which will last no more than three minutes. Report to me on the Enterprise in one hour. " " Report to you , sir? " " It is my intention to be on that ship following that meeting. Report to me in one hour. "

" Admiral, we have just spent eighteen months redesigning and refitting the Enterprise . How in the name of hell do they expect me to have her ready in twelve hours?! "

" Mr. Scott, an alien object of unbelievable destructive power is less than three days away from this planet. The only starship in interception range is the Enterprise . Ready or not, she launches in twelve hours. "

" He wanted her back, he got her. " " And Captain Decker? He's been with the ship every minute of her refitting. " " Ensign, the possibilities of our returning from this mission in one piece may have just doubled."

" I'm replacing you as captain of the Enterprise . You'll stay on as executive officer, temporary grade reduction to commander. " " You personally are assuming command? " " Yeah. " " May I ask why? " " My experience. Five years out there, dealing with unknowns like this. My familiarity with the Enterprise , this crew. "

" Admiral, this is an almost totally new Enterprise . You don't know her a tenth as well as I do. " " That's why you're staying aboard. I'm sorry, Will. " " No, sir. I don't think you're sorry. Not one damn bit. I remember when you recommended me for this command. You told me how envious you were, and how you hoped you'd be given a starship command again. Well, sir, it looks like you found a way. " " Report to the bridge, commander. Immediately. " " Aye, sir. "

"Enterprise, what we got back didn't live long. Fortunately. "

" Just a moment, captain, sir. I'll explain what happened. Your revered Admiral Nogura invoked a little known, seldom used reserve activation clause! In simpler language, captain, they drafted me! "

" Why is any object we don't understand always called a thing? "

" Well, Jim, I hear Chapel's an MD now. Well, I'm gonna need a top nurse, not a doctor who'll argue every little diagnosis with me! And they've probably redesigned the whole sickbay, too! I know engineers. They love to change things! "

" Thrusters ahead, Mr. Sulu. Take us out! "

" Well, Bones, do the new medical facilities meet with your approval? " " They do not. It's like working in a damn computer center! "

" No casualties reported, doctor. " " Wrong, Mr. Chekov, there are casualties. My wits! As in, frightened out of, captain, sir! "

" Mister Spock! " " Well, so help me, I'm actually pleased to see you! "

" Spock, you haven't changed a bit. You're just as warm and sociable as ever. " " Nor have you, doctor, as your continued predilection for irrelevancy demonstrates. "

" Will you please sit down ! "

" Mr. Decker, I will not provoke an attack. If that order isn't clear enough for you - " " Captain, as your exec, it's my duty to point out alternatives. " " Yes it is. I stand corrected. "

" I sense... puzzlement. We have been contacted. Why have we not replied? " " Contacted? How? "

" Moving into that cloud, at this time, is an unwarranted gamble. " " How do you define unwarranted? " " You asked my opinion, sir. "

" Don't interfere with it! " " Absolutely I will not interfere! " " No one interfere! It doesn't seem interested in us. Only the ship. "

" It's taking control of the computer! " " It's running our records! Earth's defenses! Starfleet's strength! "

"This is how I define unwarranted! "

" I don't want him stopped! I want him to lead me to whatever is out there. " " And if that whatever has taken over his mind...?! " " Then, he'll still have led me to it, won't he? "

" Spock, this child is about to wipe out every living thing on Earth. Now what do you suggest we do? Spank it? "

" Your child is having a tantrum, Mr. Spock! "

" I weep for V'ger as I would for a brother. As I was when I came aboard, so is V'ger now. Empty. Incomplete. Searching. Logic and knowledge are not enough. "

" Each of us, at some time in our life, turns to someone – a father, a brother, a god – and asks: Why am I here? What was I meant to be? V'ger hopes to touch its creator to find its answers. " " "Is this all that I am? Is there nothing more? "

" Capture God...? V'ger 's liable to be in for one hell of a disappointment. "

" Jim, I want this! As much as you wanted the Enterprise , I want this! "

" We witnessed a birth. Possibly a next step in our evolution. " " Well, it's been a long time since I delivered a baby and I hope we got this one off to a good start. "

" List them as missing. "

" Heading, sir? " " Out there. Thataway! "

Background information [ ]

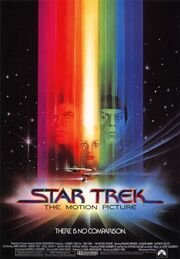

The theatrical poster for Star Trek: The Motion Picture

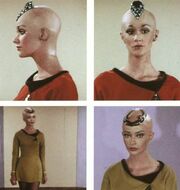

From left to right: Robert Wise, William Shatner, Gene Roddenberry, DeForest Kelley, and Leonard Nimoy

- This film was the last Star Trek release to occur in the 1970s, and the only live-action one to take place in that decade.

- Grace Lee Whitney ( Janice Rand ) and Mark Lenard (Klingon captain) are the only actors, besides the original cast, to appear in both this film and the final Star Trek: The Original Series film, Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country . Lenard plays the Klingon captain in The Motion Picture and Ambassador Sarek in The Undiscovered Country , while Whitney plays Janice Rand in both films.

- Likewise, Majel Barrett and Leonard Nimoy are the only original series actors to participate in both this film and the first Star Trek film set in the rebooted timeline , Star Trek . In The Motion Picture , Barrett played Dr. Chapel and in Star Trek she voiced the computer for the alternate reality USS Enterprise , while in both films Nimoy portrayed Spock (in the 2009 film he played the Spock of the original "Prime" timeline). However, James Doohan 's son Chris also appeared in both this film and the 2009 film. In The Motion Picture he is in the recreation deck scene (with his twin brother Montgomery) when Kirk addresses the entire crew; and in Star Trek he is in the transporter room scenes as an engineering lieutenant commander. Concurrently, Barrett and Nimoy are the only two cast members from the original pilot " The Cage " to appear in this first Star Trek film. Nevertheless, Nimoy is the only actor to portray the same character in both productions, having played Spock in both, whereas Barrett played Number One in the pilot and Dr. Chapel in the film.

- Also, Nimoy is the only actor to participate in both this film and Star Trek Into Darkness . In both films, Nimoy portrayed Spock.

- Bruce Logan was the director of photography for the Klingon scenes. He was scheduled to be the Director of Photography (DP) on "In Thy Image", the un-produced pilot for Star Trek: Phase II , the immediate predecessor television project of the film. Both the plot and script emerged from the un-produced pilot.

- One of the most persistent myths in Star Trek -lore, erroneously propagated in numerous reference works such as Star Trek Movie Memories , Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series , Star Trek - Where No One Has Gone Before , to name but a few, is that the 1977 science fiction film Close Encounters of the Third Kind played a decisive key role (besides Star Wars ) in the decision to upgrade Phase II to The Motion Picture . Actually, the upgrade decision was already firmly in place for nearly a month before Close Encounters even premiered. It was Star Wars , and Star Wars alone, that had been the prime motivator for the upgrade decision. The reference book Return to Tomorrow - The Filming of Star Trek: The Motion Picture , which contains a contemporary account of the production history but was only released in 2014, confirmed this to be the case (p. 48) Still, in the mind of the studio executives, the phenomenal success of Close Encounters served as the validation of their decision. ( see Production history below )

- Fred Phillips saved Leonard Nimoy's ear molds from the Original Series. They were put back into use when the molds being made for the film were damaged.

- Principal photography, the filming of scenes which required the principal cast, began on 7 August 1978 and was finished on 26 January 1979 .

- The theme from the TV series is heard three times in the film. Each time it is used, it is for a "captain's log" dictation. The first one is heard just before Kirk engages the Enterprise 's first warp test. The second time is when Spock is making his repairs to the warp drive, and the third time is when Kirk and McCoy are watching Decker and the Ilia-probe from Kirk's quarters.

- This film, and the last TOS cast film ( Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country ), are the only two that do not use the original series fanfare in the opening credits of the film. That fanfare was not heard at all in the score to this film, and did not make an appearance until Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan . Jerry Goldsmith did, however, bring the fanfare back for the subsequent Star Trek films he scored.

- According to David Gerrold 's The World of Star Trek , a blooper occurred in the scene where Kirk and Spock leave to investigate the intruder alert, William Shatner , as Kirk, tells Stephen Collins as Decker, that he has the bridge and Collins jumped down to the floor, grabbed the command chair and yelled like Daffy Duck, " It's mine! It's mine! At last it's mine! All mine! " which led Shatner to turn around and yell " I take it back! "

- The five previous ships named Enterprise , which Decker shows the Ilia probe in the rec room are, according to Mike Okuda's DVD text commentary , an 18th century frigate, the much decorated World War II carrier , the space shuttle orbiter prototype, an unseen ship which was actually an early Matt Jefferies design for the TV Enterprise and of course, the original configuration of the Enterprise from the original series. Internet rumors from 2001 speculated that the unseen ship might be replaced by the NX-01 Enterprise ; however, this did not happen. Christopher L. Bennett 's novel Ex Machina establishes (albeit non-canonically) that the image of the NX-01 Enterprise was added after the events of this film. Incidentally, it was Jefferies, who had provided both the historical lineage concept and the artwork upon which the backlit transparencies of the vessels were based, for the Motion Picture 's immediate predecessor, Phase II . It has set a tradition that was adhered to in the Star Trek: The Next Generation series and films, as well as in Star Trek: Enterprise . ( The Making of Star Trek: The Motion Picture , p. 94)

- According to an article written by Harlan Ellison (writer of the acclaimed Original Series episode " The City on the Edge of Forever ") and published in Starlog in 1980, Gene Roddenberry took Harold Livingston to arbitration with the Writer's Guild of America five times, seeking a screen credit for the film's screenplay. The Writer's Guild apparently sided with Livingston, as Roddenberry never received any credit for the script. However Alan Dean Foster did successfully arbitrate with the Writer's Guild as he had initially received no story credit at all, even though he had written an early draft of the " In Thy Image " script which was rewritten into the TMP script.

- The film was one of only a few Hollywood productions, and also one of the last along with Disney's The Black Hole , that introduces the film with an overture – a practice commonly used for "epic" films. For that purpose, Jerry Goldsmith chose to present the auditory "Ilia's Theme", which he also referred to as a "love theme". The overture runs for approximately three minutes, and is then taken over by the film's concise main theme (which later became famous as TNG's main title) ( 20th Anniversary Special Edition soundtrack booklet).

- This film marks the first depiction of Earth in the 23rd century. Although a parkland near Christopher Pike 's native Mojave was seen in TOS : " The Cage ", this was merely an illusion created by the Talosians . Every subsequent film except for Star Trek: Insurrection and Star Trek Beyond has included a scene set on Earth in the future.

- Academy Award-winning film legend Orson Welles provided the narration for many of the film's trailers. Director Robert Wise worked as film editor on Welles' first two films, Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons .

- Star Trek: The Motion Picture was one of the last heavily-marketed, non-animated big studio films with just a G rating, and the only Star Trek film to receive this rating (although in 2001, the director's cut got a PG for sci-fi action and mild language). Ever since, such productions were released with at least a PG rating. ( citation needed • edit )

- The Star Trek newspaper comic strip was launched in coordination with this film, four days prior to its premiere. The character of Ilia is inexplicably featured in the first two story arcs, even though they take place after the events of the film.

- The world premiere of the film took place at the K-B MacArthur Theater in Washington, DC on 6 December 1979 as a fund-raising event for the National Space Club . With thousands of Trekkies expected to attend, the event fell somewhat flat as only about three hundred showed up due to bad weather. A black tie affair, it was followed by a reception with all the film's stars and Gene Roddenberry at the Smithsonian Institute's National Air and Space Museum , complete with an orchestra playing the Jerry Goldsmith theme (some internet sites incorrectly state it was at the Kennedy Center ). The admission price to the reception for non-affiliated guests was a, for the time, hefty US$100. ( The Washington Post , 6 December 1979, p. C12; 7 December 1979, pp. C1, C3)

- In the United Kingdom, the film had a gala premiere at the Empire Leicester Square Cinema in London on 15 December 1979 . All of the principal cast attended. The Motion Picture was released theatrically on 21 December. At the time, to generate interest in the film, the BBC was re-running the series on television. The Motion Picture enjoyed a three week stint at the top of the UK box office and grossed £4,774,456 overall. [1]

- Paramount sought and obtained a variety of design patents on some costumes, ships, and props from this film, which directly resulted from Dawn Steel 's merchandising fund drive. ( see below ) They would continue to do so for the next two films, as well as for the first season of Star Trek: The Next Generation .

- The film was adapted as a novel and as a three-part comic , as well as becoming the third of five official Star Trek productions to be adapted into View-Master reels.

- Several props and costumes from this film were sold off on the It's A Wrap! sale and auction on eBay, including Walter Koenig 's uniform, [2] William Shatner's uniform, [3] a bio-monitor , [4] a beige class-B Starfleet uniform, [5] a brown class-A uniform belt, [6] several uniform patches, [7] [8] [9] a schematic lot of Enterprise deck one's exterior, [10] and many background uniforms and civilian costumes. [11] [12] [13]

- In his commentary on the Star Trek DVD, J.J. Abrams (who can be seen in the DVD's gag reel wearing a TMP production jacket) stated that the reveal of the new Enterprise in that film was, as much as possible, intended as an homage to the "amazing" shuttle sequence where Kirk sees the refit Enterprise for the first time.

It is somewhat unclear as to what exact year the first Star Trek film took place. Star Trek: Star Charts (p. 39) and the Star Trek Encyclopedia , 3rd ed., p. 691 place The Motion Picture in 2271 , stating that it took place 2.5 years after the end of the last five-year mission that, according to the Encyclopedia , took place from 2264 to 2269 . This was based on Decker's line to Kirk, that the latter had " not logged a single star hour in the last two-and-a-half years, " and Kirk's line to Scott, " Well, two and a half years as Chief of Starfleet Operations may have made me a bit stale, but I certainly wouldn't exactly consider myself untried. " This indicates a minimum of two-and-a-half years between the time the Enterprise returned to dry dock and the beginning of the first film.

In 2019, StarTrek.com released a timeline video of events in the Star Trek universe, placing The Motion Picture in 2273. [14] On screen, in VOY : " Q2 ", it is stated that Kirk's five-year mission ended in 2270 . This would establish the earliest point at which The Motion Picture could possibly have taken place some time in either 2272 or 2273 (depending on at what point in 2270 the ship ended the five-year mission). On the other end of the spectrum, the latest this film could have taken place is in 2278 , since the red The Wrath of Khan -style uniforms were in use by some time that year based on TNG : " Cause And Effect ". The stardates mentioned in the film cannot be used to accurately date the events, since the four-digit stardates beginning with the digit "7" were used for fifteen years between 2270 and 2284 , based on " Bem ", " The Ensigns of Command ", and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan . The final TAS episode, TAS : " The Counter-Clock Incident ", takes place in 2270 , as does the entire second season of the series.

Toward the end of the film, Commander Decker tells Captain Kirk, " NASA – National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Jim, this vessel was launched over three hundred years ago ", and given that the Voyager 6 probe would presumably have been launched some time after Voyager 1 and 2 , which were launched in 1977, then this would put a lower limit of 2278 on the year of the film's events.

Apocryphally, the dating of the film has been set by Pocket Books to be 2273 in their 2006 chronology Voyages of Imagination . The novel Triangle supports this dating, as it is set after The Motion Picture, and takes place seven years after " Amok Time ", in 2274 . Also, the novelization of the film written by Gene Roddenberry states that it has been 2.8 years (nine Vulcan seasons) since Spock left the crew. Due to all this obscurity, however, Memory Alpha leaves the exact canonical dating open, and simply dates the film in the 2270s .

Costs and revenues [ ]

According to the Guinness Book of Records , when the film was produced, it was the most expensive theatrical feature ever made with a total production cost of US$46 million (or $44 million, according to the reference book Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series , p. 75). This proved incorrect however, as Superman: The Movie had an even higher budget at US$54 million, though the producers didn't give the exact figure for some years afterward. This doesn't take inflation into account, however; taking it into account, Cleopatra was, at the time, the most expensive film ever made. And even Cleopatra was arguably surpassed by far by the Soviet-made version of Tolstoy's War and Peace , the 1966 (four-part) film Voyna i mir , reported to have been produced at a for the time staggering US$100 million budget. [15]

The original production budget for Star Trek: The Motion Picture , set at US$15 million, included the costs made for the aborted Star Trek: Phase II series, as well as the earlier false starts in getting a Star Trek film off the ground. ( Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series , pp. 34, 69) The inclusion of these costs is debatable from a business economics point of view, since anywhere else in the corporate world research and development costs of projects that do not come to fruition are usually written off and are commonly charged against the balance sheets of corporations. This is a sound business generally accepted accounting principle (as stated in any business economics text book and where the principles are known under their acronym GAAP's) since it prevents cost price inflation with undue elements, therefore avoiding pollution of their viability assessment, of products that do come to fruition. Still, in the particular case of Phase II , an argument could be made for carrying over production costs already incurred to the Motion Picture , since some of those costs were applicable to the Motion Picture as well, such as those of the sets that were already constructed and the fees for production staff and cast already paid, who continued to work on the film.

This film was pre-sold in the autumn of 1978, while it was still in production, to the ABC TV network for US$15 million – or $10 million, according to performer Walter Koenig. ( Starlog , issue 32, p. 58) That fee allowed two airings of the film, the first to run no earlier than December 1982 . Its ABC premiere was on 20 February 1983 , and its second run was in March 1987 (ABC ran the film a third and final time in the summer of 1989). The television run of the film marks one of the first times that scenes not incorporated into a theatrical cut were reintegrated for the television airing, making the television cut longer than the theatrical cut.

Another revenue guarantee the studio secured was the amount of US$35 million that theater owners committed to, provided the film was released on 7 December 1979 as announced, allowing them to plan for the Christmas season. It was exactly for this reason that the studio could not deviate from the release date, even if they had wanted to, when the visual effects debacle occurred in February 1979, which left the production in dire straits ( see below ). Barry Diller , then studio head and chief financial overseer of the production, recalled, " Once the theater owners realized that we pulled this scam off on them, none of them liked it. They were all trying to get out of it and we wouldn't let them out of it and we knew, of course, that if we didn't open this picture on December 7, the guarantees would evaporate... " ( The Keys to the Kingdom , 2000, Chapter 6) The actual potential financial damage was reportedly even far greater than Diller led to believe, as the studio, in case of non-timely release, not only forfeited the guarantees, but had also to pay out the same amount to the distributors as damages (a not uncommon reciprocal feature for this kind of arrangements), meaning the total financial damage would amount to US$70 million according to Animation and Graphics Artist Leslie Ekker . ( Return to Tomorrow - The Filming of Star Trek: The Motion Picture , p. 351) It was more than enough reason to have the release date set in stone.

In the spring of 1979, a second revenue source was additionally tapped long before the film premiered, necessitated by the February visual effects debacle, which had left the studio without cash to finish the film. Charged with creating that stream was recently appointed vice-president of Marketing and Licensing , studio executive Dawn Steel. Then novice studio producer Jerry Bruckheimer recalled, " I was here doing American Gigolo when they were doing Star Trek . The budget was going up, up, up. They needed money to cover the negative. Eisner went to Dawn and said, "I want X amount of guarantees for this merchandising." She went to conventions and got every toy-maker, anyone who made T-shirts and key chains and raised every nickel she could. She shook the trees. There hasn't been that energy vortex in merchandise since she left. " Steel however, had a problem since the production was running over schedule by that time, as she clarified, " I was a desperate person. There was no product, because there was no movie to show anyone. So I had to this razzmatazz bit onstage, so I could convince the people making pajamas and toys and Coca-Cola and McDonald's to do the tie-ins. I figured out this laser thing. I beamed myself onto the stage. " Held in the largest theater on the Paramount lot, and joined in a similar fashion by the principal cast, the imaginative presentation was met with rambunctious enthusiasm. " It was the most unbelievable party Paramount ever had. ", another attending studio producer, Brian Grazer, remembered. As already indicated by Steel, the, at the time, most unlikely corporations to sign up were Coca-Cola and fast-food company McDonald's, " Coca-Cola bought all this network time to advertise our movie. It had never been done before. ", Steel enthused. Crudely drawn comic strips (as no other imagery was available) were subsequently featured on the containers of both companies, a legendary one featured on those of McDonald's, featuring Klingons eating hamburgers and drinking Coca-Cola. Often incorrectly credited as McDonalds's very first outing in their "Happy Meal" concept, The Motion Picture was nevertheless their first themed one, coming from December 1979 onward in five boxes with items included such as bracelets, puzzles and the like. McDonald's ran several thirty second television commercials, promoting the Motion Picture Happy Meals, one of them featuring a Klingon, endorsing them in, what was supposed to be, Klingonese. Impressed with her performance, studio COO Michael Eisner promoted Steel the following day to vice-president of productions in features, having been less than six months in the employment of Paramount, and she went on to become one of the first female "Hollywood Moguls" by holding a position as studio head in the then predominantly male-dominated industry. ( New York magazine, 29 May 1989, p. 45; Star Trek: The Complete Unauthorized History , pp. 108-109) The amount thus generated for the studio has never been disclosed, though Steel herself has given a conservative low estimate of at least $250 million dollar in total sales of licensed Star Trek -related merchandise, of which, "depending on the product", 1 to 11 percent were fees for the studio. ( Playboy magazine, January 1980, p. 310)

Arguably, Steel not only saved the film, but the entire studio as well with her fund drive. Not only were the US$35 million dollar payable as damages to distributors avoided, but also the loss of the approximately same amount, already sunk in the production. That money had not been Paramount's own, but had been a loan from the obscure investment company Century Associates . When Gulf+Western 's Charles Bluhdorn bought Paramount Pictures in 1966, the studio was in dire straits, rapidly descending towards bankruptcy. It took nearly seven years to painfully restructure the company and reverse its fortunes, and it was only by the mid-1970s that the studio became profitable again, albeit still somewhat tentatively. It was therefore that the studio still did not yet possess a war-chest large enough, to fully fund their own productions on their own, when The Motion Picture came along. It would not have been the first time that a studio was killed off by an overly ambitious film project, nor would it be the last time; Previously, in 1957, RKO Pictures was terminated as an independent film production company by its owners (some of its remnants absorbed by Paramount and Desilu , as the former RKO property was adjacent to those of both), due to the fact that John Wayne's 1956 epic, The Conquerers , failed to earn back its production budget. And only one year later, the 1980 western, Heaven's Gate , the US$44 million budget box-office disaster, ended United Artists , its remnants absorbed by MGM , though keeping the name as a separate dependent division.

Having avoided the fate of Heaven's Gate , the Motion Picture earned US$11,926,421 in its opening weekend at the US box office, a record at the time, and its total domestic gross theatrical revenue was US$82,258,456 .