You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

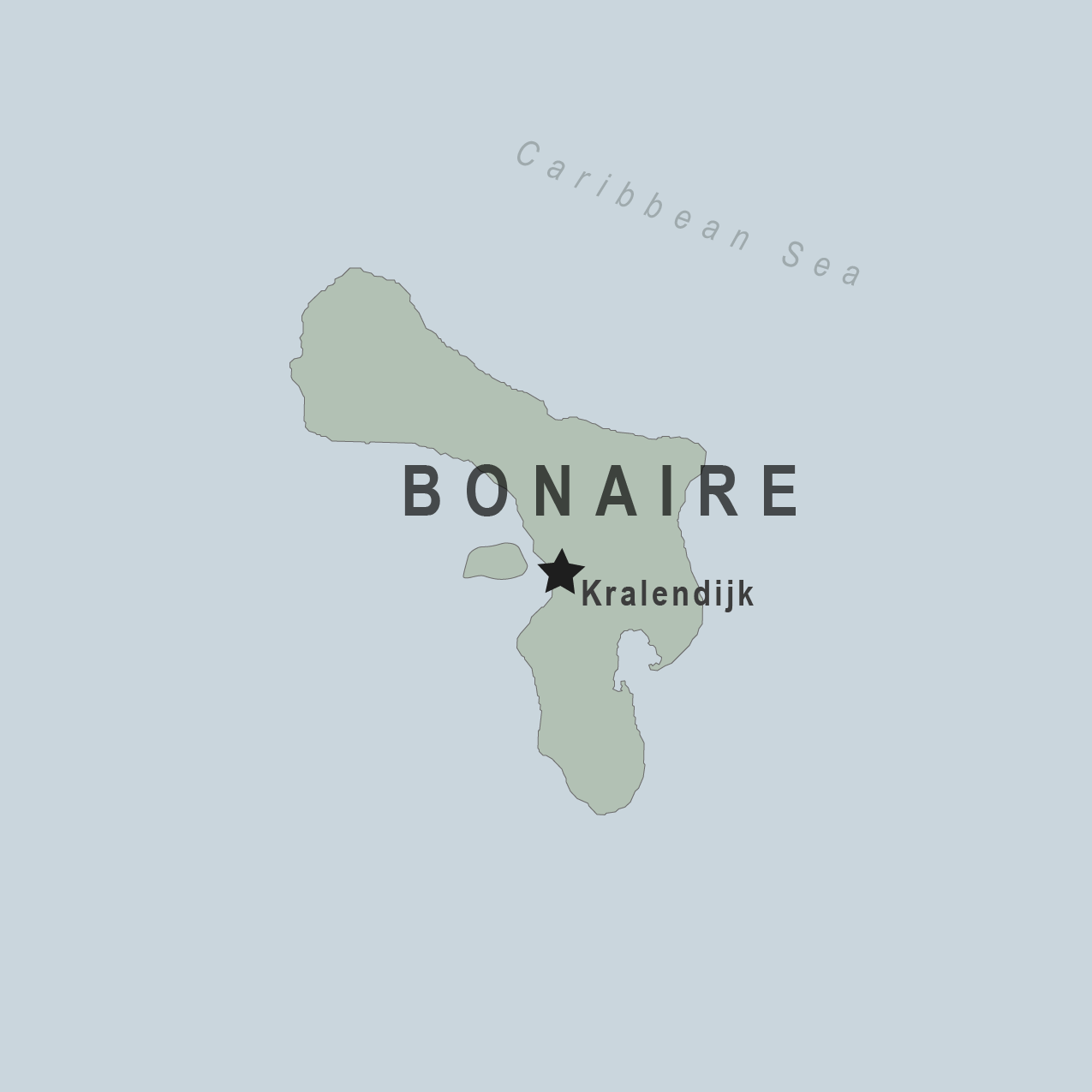

Bonaire Traveler View

Travel health notices, vaccines and medicines, non-vaccine-preventable diseases, stay healthy and safe.

- Packing List

After Your Trip

There are no notices currently in effect for Bonaire.

⇧ Top

Check the vaccines and medicines list and visit your doctor at least a month before your trip to get vaccines or medicines you may need. If you or your doctor need help finding a location that provides certain vaccines or medicines, visit the Find a Clinic page.

Routine vaccines

Recommendations.

Make sure you are up-to-date on all routine vaccines before every trip. Some of these vaccines include

- Chickenpox (Varicella)

- Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis

- Flu (influenza)

- Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR)

Immunization schedules

All eligible travelers should be up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines. Please see Your COVID-19 Vaccination for more information.

COVID-19 vaccine

Hepatitis A

Recommended for unvaccinated travelers one year old or older going to Bonaire.

Infants 6 to 11 months old should also be vaccinated against Hepatitis A. The dose does not count toward the routine 2-dose series.

Travelers allergic to a vaccine component or who are younger than 6 months should receive a single dose of immune globulin, which provides effective protection for up to 2 months depending on dosage given.

Unvaccinated travelers who are over 40 years old, immunocompromised, or have chronic medical conditions planning to depart to a risk area in less than 2 weeks should get the initial dose of vaccine and at the same appointment receive immune globulin.

Hepatitis A - CDC Yellow Book

Dosing info - Hep A

Hepatitis B

Recommended for unvaccinated travelers of all ages traveling to Bonaire.

Hepatitis B - CDC Yellow Book

Dosing info - Hep B

Cases of measles are on the rise worldwide. Travelers are at risk of measles if they have not been fully vaccinated at least two weeks prior to departure, or have not had measles in the past, and travel internationally to areas where measles is spreading.

All international travelers should be fully vaccinated against measles with the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, including an early dose for infants 6–11 months, according to CDC’s measles vaccination recommendations for international travel .

Measles (Rubeola) - CDC Yellow Book

Dogs infected with rabies are not commonly found in Bonaire.

If rabies exposures occur while in Bonaire, rabies vaccines are typically available throughout most of the country.

Rabies pre-exposure vaccination considerations include whether travelers 1) will be performing occupational or recreational activities that increase risk for exposure to potentially rabid animals and 2) might have difficulty getting prompt access to safe post-exposure prophylaxis.

Please consult with a healthcare provider to determine whether you should receive pre-exposure vaccination before travel.

For more information, see country rabies status assessments .

Rabies - CDC Yellow Book

Recommended for most travelers, especially those staying with friends or relatives or visiting smaller cities or rural areas.

Typhoid - CDC Yellow Book

Dosing info - Typhoid

Yellow Fever

Required for travelers ≥9 months old arriving from countries with risk for YF virus transmission; this includes >12-hour airport transits or layovers in countries with risk for YF virus transmission. 1

Yellow Fever - CDC Yellow Book

Avoid contaminated water

Leptospirosis

How most people get sick (most common modes of transmission)

- Touching urine or other body fluids from an animal infected with leptospirosis

- Swimming or wading in urine-contaminated fresh water, or contact with urine-contaminated mud

- Drinking water or eating food contaminated with animal urine

- Avoid contaminated water and soil

- Avoid floodwater

Clinical Guidance

Avoid bug bites.

- Mosquito bite

- Avoid Bug Bites

- An infected pregnant woman can spread it to her unborn baby

Airborne & droplet

- Breathing in air or accidentally eating food contaminated with the urine, droppings, or saliva of infected rodents

- Bite from an infected rodent

- Less commonly, being around someone sick with hantavirus (only occurs with Andes virus)

- Avoid rodents and areas where they live

- Avoid sick people

Tuberculosis (TB)

- Breathe in TB bacteria that is in the air from an infected and contagious person coughing, speaking, or singing.

Learn actions you can take to stay healthy and safe on your trip. Vaccines cannot protect you from many diseases in Bonaire, so your behaviors are important.

Eat and drink safely

Food and water standards around the world vary based on the destination. Standards may also differ within a country and risk may change depending on activity type (e.g., hiking versus business trip). You can learn more about safe food and drink choices when traveling by accessing the resources below.

- Choose Safe Food and Drinks When Traveling

- Water Treatment Options When Hiking, Camping or Traveling

- Global Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH)

- Avoid Contaminated Water During Travel

You can also visit the Department of State Country Information Pages for additional information about food and water safety.

Prevent bug bites

Bugs (like mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas) can spread a number of diseases in Bonaire. Many of these diseases cannot be prevented with a vaccine or medicine. You can reduce your risk by taking steps to prevent bug bites.

What can I do to prevent bug bites?

- Cover exposed skin by wearing long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and hats.

- Use an appropriate insect repellent (see below).

- Use permethrin-treated clothing and gear (such as boots, pants, socks, and tents). Do not use permethrin directly on skin.

- Stay and sleep in air-conditioned or screened rooms.

- Use a bed net if the area where you are sleeping is exposed to the outdoors.

What type of insect repellent should I use?

- FOR PROTECTION AGAINST TICKS AND MOSQUITOES: Use a repellent that contains 20% or more DEET for protection that lasts up to several hours.

- Picaridin (also known as KBR 3023, Bayrepel, and icaridin)

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) or para-menthane-diol (PMD)

- 2-undecanone

- Always use insect repellent as directed.

What should I do if I am bitten by bugs?

- Avoid scratching bug bites, and apply hydrocortisone cream or calamine lotion to reduce the itching.

- Check your entire body for ticks after outdoor activity. Be sure to remove ticks properly.

What can I do to avoid bed bugs?

Although bed bugs do not carry disease, they are an annoyance. See our information page about avoiding bug bites for some easy tips to avoid them. For more information on bed bugs, see Bed Bugs .

For more detailed information on avoiding bug bites, see Avoid Bug Bites .

Stay safe outdoors

If your travel plans in Bonaire include outdoor activities, take these steps to stay safe and healthy during your trip.

- Stay alert to changing weather conditions and adjust your plans if conditions become unsafe.

- Prepare for activities by wearing the right clothes and packing protective items, such as bug spray, sunscreen, and a basic first aid kit.

- Consider learning basic first aid and CPR before travel. Bring a travel health kit with items appropriate for your activities.

- If you are outside for many hours in heat, eat salty snacks and drink water to stay hydrated and replace salt lost through sweating.

- Protect yourself from UV radiation : use sunscreen with an SPF of at least 15, wear protective clothing, and seek shade during the hottest time of day (10 a.m.–4 p.m.).

- Be especially careful during summer months and at high elevation. Because sunlight reflects off snow, sand, and water, sun exposure may be increased during activities like skiing, swimming, and sailing.

- Very cold temperatures can be dangerous. Dress in layers and cover heads, hands, and feet properly if you are visiting a cold location.

Stay safe around water

- Swim only in designated swimming areas. Obey lifeguards and warning flags on beaches.

- Practice safe boating—follow all boating safety laws, do not drink alcohol if driving a boat, and always wear a life jacket.

- Do not dive into shallow water.

- Do not swim in freshwater in developing areas or where sanitation is poor.

- Avoid swallowing water when swimming. Untreated water can carry germs that make you sick.

- To prevent infections, wear shoes on beaches where there may be animal waste.

Keep away from animals

Most animals avoid people, but they may attack if they feel threatened, are protecting their young or territory, or if they are injured or ill. Animal bites and scratches can lead to serious diseases such as rabies.

Follow these tips to protect yourself:

- Do not touch or feed any animals you do not know.

- Do not allow animals to lick open wounds, and do not get animal saliva in your eyes or mouth.

- Avoid rodents and their urine and feces.

- Traveling pets should be supervised closely and not allowed to come in contact with local animals.

- If you wake in a room with a bat, seek medical care immediately. Bat bites may be hard to see.

All animals can pose a threat, but be extra careful around dogs, bats, monkeys, sea animals such as jellyfish, and snakes. If you are bitten or scratched by an animal, immediately:

- Wash the wound with soap and clean water.

- Go to a doctor right away.

- Tell your doctor about your injury when you get back to the United States.

Consider buying medical evacuation insurance. Rabies is a deadly disease that must be treated quickly, and treatment may not be available in some countries.

Reduce your exposure to germs

Follow these tips to avoid getting sick or spreading illness to others while traveling:

- Wash your hands often, especially before eating.

- If soap and water aren’t available, clean hands with hand sanitizer (containing at least 60% alcohol).

- Don’t touch your eyes, nose, or mouth. If you need to touch your face, make sure your hands are clean.

- Cover your mouth and nose with a tissue or your sleeve (not your hands) when coughing or sneezing.

- Try to avoid contact with people who are sick.

- If you are sick, stay home or in your hotel room, unless you need medical care.

Avoid sharing body fluids

Diseases can be spread through body fluids, such as saliva, blood, vomit, and semen.

Protect yourself:

- Use latex condoms correctly.

- Do not inject drugs.

- Limit alcohol consumption. People take more risks when intoxicated.

- Do not share needles or any devices that can break the skin. That includes needles for tattoos, piercings, and acupuncture.

- If you receive medical or dental care, make sure the equipment is disinfected or sanitized.

Know how to get medical care while traveling

Plan for how you will get health care during your trip, should the need arise:

- Carry a list of local doctors and hospitals at your destination.

- Review your health insurance plan to determine what medical services it would cover during your trip. Consider purchasing travel health and medical evacuation insurance.

- Carry a card that identifies, in the local language, your blood type, chronic conditions or serious allergies, and the generic names of any medications you take.

- Some prescription drugs may be illegal in other countries. Call Bonaire’s embassy to verify that all of your prescription(s) are legal to bring with you.

- Bring all the medicines (including over-the-counter medicines) you think you might need during your trip, including extra in case of travel delays. Ask your doctor to help you get prescriptions filled early if you need to.

Many foreign hospitals and clinics are accredited by the Joint Commission International. A list of accredited facilities is available at their website ( www.jointcommissioninternational.org ).

In some countries, medicine (prescription and over-the-counter) may be substandard or counterfeit. Bring the medicines you will need from the United States to avoid having to buy them at your destination.

Select safe transportation

Motor vehicle crashes are the #1 killer of healthy US citizens in foreign countries.

In many places cars, buses, large trucks, rickshaws, bikes, people on foot, and even animals share the same lanes of traffic, increasing the risk for crashes.

Be smart when you are traveling on foot.

- Use sidewalks and marked crosswalks.

- Pay attention to the traffic around you, especially in crowded areas.

- Remember, people on foot do not always have the right of way in other countries.

Riding/Driving

Choose a safe vehicle.

- Choose official taxis or public transportation, such as trains and buses.

- Ride only in cars that have seatbelts.

- Avoid overcrowded, overloaded, top-heavy buses and minivans.

- Avoid riding on motorcycles or motorbikes, especially motorbike taxis. (Many crashes are caused by inexperienced motorbike drivers.)

- Choose newer vehicles—they may have more safety features, such as airbags, and be more reliable.

- Choose larger vehicles, which may provide more protection in crashes.

Think about the driver.

- Do not drive after drinking alcohol or ride with someone who has been drinking.

- Consider hiring a licensed, trained driver familiar with the area.

- Arrange payment before departing.

Follow basic safety tips.

- Wear a seatbelt at all times.

- Sit in the back seat of cars and taxis.

- When on motorbikes or bicycles, always wear a helmet. (Bring a helmet from home, if needed.)

- Avoid driving at night; street lighting in certain parts of Bonaire may be poor.

- Do not use a cell phone or text while driving (illegal in many countries).

- Travel during daylight hours only, especially in rural areas.

- If you choose to drive a vehicle in Bonaire, learn the local traffic laws and have the proper paperwork.

- Get any driving permits and insurance you may need. Get an International Driving Permit (IDP). Carry the IDP and a US-issued driver's license at all times.

- Check with your auto insurance policy's international coverage, and get more coverage if needed. Make sure you have liability insurance.

- Avoid using local, unscheduled aircraft.

- If possible, fly on larger planes (more than 30 seats); larger airplanes are more likely to have regular safety inspections.

- Try to schedule flights during daylight hours and in good weather.

Medical Evacuation Insurance

If you are seriously injured, emergency care may not be available or may not meet US standards. Trauma care centers are uncommon outside urban areas. Having medical evacuation insurance can be helpful for these reasons.

Helpful Resources

Road Safety Overseas (Information from the US Department of State): Includes tips on driving in other countries, International Driving Permits, auto insurance, and other resources.

The Association for International Road Travel has country-specific Road Travel Reports available for most countries for a minimal fee.

Maintain personal security

Use the same common sense traveling overseas that you would at home, and always stay alert and aware of your surroundings.

Before you leave

- Research your destination(s), including local laws, customs, and culture.

- Monitor travel advisories and alerts and read travel tips from the US Department of State.

- Enroll in the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program (STEP) .

- Leave a copy of your itinerary, contact information, credit cards, and passport with someone at home.

- Pack as light as possible, and leave at home any item you could not replace.

While at your destination(s)

- Carry contact information for the nearest US embassy or consulate .

- Carry a photocopy of your passport and entry stamp; leave the actual passport securely in your hotel.

- Follow all local laws and social customs.

- Do not wear expensive clothing or jewelry.

- Always keep hotel doors locked, and store valuables in secure areas.

- If possible, choose hotel rooms between the 2nd and 6th floors.

Healthy Travel Packing List

Use the Healthy Travel Packing List for Bonaire for a list of health-related items to consider packing for your trip. Talk to your doctor about which items are most important for you.

Why does CDC recommend packing these health-related items?

It’s best to be prepared to prevent and treat common illnesses and injuries. Some supplies and medicines may be difficult to find at your destination, may have different names, or may have different ingredients than what you normally use.

If you are not feeling well after your trip, you may need to see a doctor. If you need help finding a travel medicine specialist, see Find a Clinic . Be sure to tell your doctor about your travel, including where you went and what you did on your trip. Also tell your doctor if you were bitten or scratched by an animal while traveling.

For more information on what to do if you are sick after your trip, see Getting Sick after Travel .

Map Disclaimer - The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on maps do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement are generally marked.

Other Destinations

If you need help finding travel information:

Message & data rates may apply. CDC Privacy Policy

File Formats Help:

- Adobe PDF file

- Microsoft PowerPoint file

- Microsoft Word file

- Microsoft Excel file

- Audio/Video file

- Apple Quicktime file

- RealPlayer file

- Zip Archive file

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Security Alert May 17, 2024

Worldwide caution.

- Travel Advisories |

- Contact Us |

- MyTravelGov |

Find U.S. Embassies & Consulates

Travel.state.gov, congressional liaison, special issuance agency, u.s. passports, international travel, intercountry adoption, international parental child abduction, records and authentications, popular links, travel advisories, mytravelgov, stay connected, legal resources, legal information, info for u.s. law enforcement, replace or certify documents.

Before You Go

Learn About Your Destination

While Abroad

Emergencies

Share this page:

Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba

Travel Advisory July 17, 2023

Bonaire - level 1: exercise normal precautions.

Reissued with obsolete COVID-19 page links removed.

Exercise normal precautions in Bonaire.

Read the country information page for additional information on travel to Bonaire.

If you decide to travel to Bonaire:

- Enroll in the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program (STEP) to receive Alerts and make it easier to locate you in an emergency.

- Follow the Department of State on Facebook and Twitter .

- Review the Country Security Report for Bonaire.

- Prepare a contingency plan for emergency situations. Review the Traveler’s Checklist .

- Visit the CDC page for the latest Travel Health Information related to your travel.

Travel Advisory October 16, 2023

Sint eustatius - level 1: exercise normal precautions.

Reissued after periodic review without changes.

Exercise normal precautions in Sint Eustatius.

Read the country information page for additional information on travel to Sint Eustatius.

If you decide to travel to Sint Eustatius:

- Read the Department of State’s COVID-19 page before planning any international travel, and read the Consulate's COVID-19 page for country-specific information on COVID-19 information.

- Enroll in the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program (STEP) to receive Alerts and make it easier to locate you in an emergency.

- Follow the Department of State on Facebook and Twitter .

- Review the Country Security Report for Sint Eustatius.

- Prepare a contingency plan for emergency situations. Review the Traveler’s Checklist .

Saba - Level 1: Exercise Normal Precautions

Exercise normal precautions in Saba.

Read the country information page for additional information on travel to Saba.

If you decide to travel to Saba:

- Read the Department of State’s COVID-19 page before planning any international travel, and read the Consulate's COVID-19 page for country-specific COVID-19 information.

- Review the Country Security Report for Saba.

Embassy Messages

View Alerts and Messages Archive

Quick Facts

Must be valid for period of stay.

One page required for entry stamp

None required for visits up to 180 days

Yellow fever if arriving from select countries .

$10,000 (or equivalent) must be declared

Embassies and Consulates

U.s. consulate general curacao.

J.B. Gorsiraweg 1, Willemstad, Curaçao Telephone : +(599) (9) 461-3066 Emergency After-Hours Telephone: +(599) (9)843-3066 (from Curaçao); +1-(503)-420-3115 (from the United States) Email: [email protected]

Destination Description

See the Department of State’s Fact Sheet on the Netherlands for information on U.S. - Netherlands relations.

Entry, Exit and Visa Requirements

All U.S. citizens must have a U.S. passport for all air travel to and from the BES Islands. All sea travelers must have a U.S. passport or passport card. Review further information on Bonaire travel here .

Upon arrival in the BES Islands, you must have:

- proof of onward or return ticket;

- proof of sufficient funds; and

- proof of lodging accommodations for your stay.

For the most current visa information please visit the website of the Caribbean Netherlands Immigration and Naturalisation Service . For further information, travelers may contact the Royal Netherlands Embassy or its consulates in the United States. For more information on visas or extending your visit, please call the Immigration Office of Bonaire at +599-715-8330. HIV/AIDS Restrictions: The U.S. Department of State is unaware of any HIV/AIDS entry restrictions for visitors to or foreign residents of the BES Islands. Find information on dual nationality , prevention of international child abduction , and customs information on our websites.

Safety and Security

Crime: Bonaire, Saba, and Sint Eustatius are all assessed as low-crime areas as their small populations provide a high level of social control and their police forces are professional and responsive. Thoe crimes that do occur are generally non-violent, financially-motivated, and opportunistic in nature such as pickpocketing, thefts of unattended bags, and smash and grabs of empty vehicles. Do not leave valuables unattended in public areas or in unsecured hotel rooms and rental homes. Keep a copy of your valid U.S. passport in a secure location in case it is stolen. Car theft, especially of rental vehicles, can occur. Vehicle leases or rentals may not be fully covered by local insurance when a vehicle is stolen or damaged. Be sure you are sufficiently insured when renting vehicles and jet skis.

The legal drinking age of 18 is not always rigorously enforced on the BES islands, so extra parental supervision may be appropriate. Travel in pairs or groups and be responsible with alcohol consumption. For information on scams, visit the Department of State and FBI pages on scams and safety.

Victims of Crime: Dial 911 for police assistance in the BES Islands. Contact the U.S. Consulate at (+599)(9)-461-3066 after you have contacted local police. Remember that local authorities are responsible for investigating and prosecuting the crime.

Do not rely on hotels, restaurants, or tour companies to make the police report for you.

For more information, see our webpage on help for U.S. victims of crime overseas .

- help you find appropriate medical care

- assist you in reporting a crime to the police

- contact relatives or friends with your written consent

- Provide general information regarding the victim’s role during the local investigation and following its conclusion

- provide a list of local attorneys

- provide our information on victim’s compensation programs in the U.S .

- provide an emergency loan for repatriation to the United States and/or limited medical support in cases of destitution

- help you find accommodation and arrange flights home

- replace a stolen or lost passport

Domestic Violence : U.S. citizen victims of domestic violence are encouraged to contact the Consulate for assistance.

Tourism: The tourism industry is unevenly regulated, and safety inspections for equipment and facilities do not commonly occur. Hazardous areas/activities are not always identified with appropriate signage, and staff may not be trained or certified either by the host government or by recognized authorities in the field. In the event of an injury, appropriate medical treatment is typically available only in/near major cities. First responders are generally unable to access areas outside of major cities and to provide urgent medical treatment. U.S. citizens are encouraged to purchase medical evacuation insurance .

Local Laws & Special Circumstances

Criminal Penalties: You are subject to local laws. If you violate local laws, even unknowingly, you may be expelled, arrested, or imprisoned. Individuals establishing a business or practicing a profession that requires additional permits or licensing should seek information from the competent local authorities, prior to practicing or operating a business.

Furthermore, some laws are also prosecutable in the United States, regardless of local law. For examples, see our website on crimes against minors abroad and the Department of Justice website.

Arrest Notification: If you are arrested or detained, ask police or prison officials to notify the U.S. Consulate immediately. See our webpage for further information.

Dutch law allows for suspects to be held by order of a judge without a hearing during an investigation .

Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Although counterfeit and pirated goods are prevalent in many countries, they may still be illegal according to local laws. You may also pay fines or have to give them up if you bring them back to the United States. See the U.S. Department of Justice website for more information.

Faith-Based Travelers: See the following webpages for details:

- Faith-Based Travel Information

- International Religious Freedom Report – see country reports

- Human Rights Report – see country reports

- Hajj Fact Sheet for Travelers

- Best Practices for Volunteering Abroad

LGBTQI+ Travelers: There are no legal restrictions on same-sex sexual relations or the organization of LGBTQI+ events in the BES Islands.

See our LGBTQI+ Travel Information page and section 6 of our Human Rights report for further details.

Travelers with Disabilities: The law in the Dutch Caribbean prohibits discrimination against persons with physical, sensory, intellectual or mental disabilities, and the law is enforced. Social acceptance of persons with disabilities in public is as prevalent as in the United States. The most common types of accessibility may include accessible facilities, information, and communication/access to services/ease of movement or access. However, accessibility may be limited in some lodgings and general infrastructure.

- Please visit the InfoBonaire Website for Handicapped and Disabled Services for more information.

Students: See our Students Abroad page and FBI travel tips .

Women Travelers: See our travel tips for Women Travelers .

Access to quality medical care is limited on the BES Islands, and facilities do not offer the health and service standards typically expected in the United States .

For emergency services in the BES Islands, dial 911 .

Ambulance services are widely available.

A list of medical facilities in the BES Islands is available on our Consulate website. We do not endorse or recommend any specific medical provider or clinic.

We do not pay medical bills. Be aware that U.S. Medicare/Medicaid does not apply overseas. Most hospitals and doctors overseas do not accept U.S. health insurance.

Medical Insurance: Make sure your health insurance plan provides coverage overseas. Most care providers overseas only accept cash payments. See our webpage for more information on overseas insurance coverage. Visit the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for more information on type of insurance you should consider before you travel overseas.

We strongly recommend supplemental insurance to cover medical evacuation.

Medicines: Always carry your prescription medication in original packaging, along with your doctor’s prescription. If traveling with prescription medication, check with the government of the Netherlands to ensure the medication is legal in the BES islands. Always carry your prescription medication in original packaging with your doctor’s prescription.

Drug stores or “boticas” provide prescription and over-the-counter medicine. Visitors need a local prescription, and may not be able to find medications normally available in the U.S. Emergency services are usually quick to respond.

Vaccinations: Be up-to-date on all vaccinations recommended by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Use the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended mosquito repellents and sleep under insecticide-impregnated mosquito nets. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended for all travelers even for short stays.

Visit the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website for more information about Resources for Travelers regarding specific issues in the BES Islands.

Further health information:

- World Health Organization

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Air Quality: Visit AirNow Department of State for information on air quality at U.S. Embassies and Consulates.

Travel and Transportation

Road Conditions and Safety: Nonexistent, hidden, and poorly maintained street signs are a major road hazard on the BES islands. Proceed through intersections with caution. Roads can be extremely slippery during rainfall. Night driving is reasonably safe if you are familiar with the route and road conditions. Many streets are poorly lit or not lit at all. In Bonaire and St. Eustatius, be vigilant for wild donkeys or other animals crossing the road. Use caution when driving in Saba as roads tend to be steep and have many sharp turns.

The emergency service telephone number is 911. Police and ambulances tend to respond quickly to emergency situations.

Traffic Laws: Driving on the BES islands is on the right hand side. Right turns on red are prohibited and traffic conditions require somewhat defensive driving. Local laws require drivers and passengers to wear seat belts and motorcyclists to wear helmets. Children under 4 years of age must be in child safety seats, and children under 12 must ride in the back seat.

Public Transportation: Taxis are an easy form of transportation on the islands. Verify the price before entering the taxi, as there are no meters. Fares are quoted in U.S. dollars. In Bonaire, public minibuses are inexpensive and run nonstop during the day with no fixed schedule. Each minibus has a specific route displayed on the windshield. Buses, which run on the hour, have limited routes. The road conditions on the main thoroughfares are good to fair. There is no public transportation in Saba or St. Eustatius.

See our Road Safety page for more information.

Aviation Safety Oversight: The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has assessed the government of the BES Islands’ Civil Aviation Authority as being in compliance with International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) aviation safety standards for oversight of BES Islands’ air carrier operations. Further information may be found on the FAA’s safety assessment page .

Maritime Travel: Mariners planning travel to the BES Islands should also check for U.S. maritime advisories and alerts . Information may also be posted to the U.S. Coast Guard homeport website , and the NGA broadcast warnings .

For additional travel information

- Enroll in the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program (STEP) to receive security messages and make it easier to locate you in an emergency.

- Call us in Washington, D.C. at 1-888-407-4747 (toll-free in the United States and Canada) or 1-202-501-4444 (from all other countries) from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m., Eastern Standard Time, Monday through Friday (except U.S. federal holidays).

- See the State Department’s travel website for the Worldwide Caution and Travel Advisories .

- Follow us on Twitter and Facebook .

- See traveling safely abroad for useful travel tips.

Review information about International Parental Child Abduction in Bonaire, St. Eustatius, and Saba (BES) . For additional IPCA-related information, please see the International Child Abduction Prevention and Return Act ( ICAPRA ) report.

Travel Advisory Levels

Assistance for u.s. citizens, bonaire, sint eustatius and saba map, country map, sint eustatius, learn about your destination, enroll in step.

Subscribe to get up-to-date safety and security information and help us reach you in an emergency abroad.

Recommended Web Browsers: Microsoft Edge or Google Chrome.

Check passport expiration dates carefully for all travelers! Children’s passports are issued for 5 years, adult passports for 10 years.

Afghanistan

Antigua and Barbuda

Bosnia and Herzegovina

British Virgin Islands

Burkina Faso

Burma (Myanmar)

Cayman Islands

Central African Republic

Cote d Ivoire

Curaçao

Czech Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Dominican Republic

El Salvador

Equatorial Guinea

Eswatini (Swaziland)

Falkland Islands

France (includes Monaco)

French Guiana

French Polynesia

French West Indies

Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Martin, and Saint Barthélemy (French West Indies)

Guinea-Bissau

Isle of Man

Israel, The West Bank and Gaza

Liechtenstein

Marshall Islands

Netherlands

New Caledonia

New Zealand

North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea)

Papua New Guinea

Philippines

Republic of North Macedonia

Republic of the Congo

Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Lucia

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Sao Tome and Principe

Saudi Arabia

Sierra Leone

Sint Maarten

Solomon Islands

South Africa

South Korea

South Sudan

Switzerland

The Bahamas

Timor-Leste

Trinidad and Tobago

Turkmenistan

Turks and Caicos Islands

United Arab Emirates

United Kingdom

Vatican City (Holy See)

External Link

You are about to leave travel.state.gov for an external website that is not maintained by the U.S. Department of State.

Links to external websites are provided as a convenience and should not be construed as an endorsement by the U.S. Department of State of the views or products contained therein. If you wish to remain on travel.state.gov, click the "cancel" message.

You are about to visit:

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

Every Caribbean Island's COVID-19 Travel Policies — and What You Need to Know to Plan Your Trip

Almost every Caribbean destination is open to travelers regardless of vaccination status.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Jamie-Aranoff-81160df91135499b952b796e76110d88.jpg)

When COVID-19 struck the United States in late winter 2020 relaxing on a warm beach with a subtle island breeze was all anyone could want. Now, almost two years since, most Caribbean islands have fully reopened to travelers.

Below is an island-by-island guide for U.S. travelers with everything you need to know before planning a trip to the Caribbean.

As of Oct. 1, there are no entry requirements to Anguilla, according to the U.S. Embassy

Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda have removed all preexisting COVID-19 entry requirements, according to the government. However, any passenger displaying symptoms may be isolated by the government.

Aruba has waived all preexisting COVID-19 entry level requirements, however, travel insurance is highly recommended, according to the country's tourism site.

Non-U.S. citizens must show proof of vaccination, and there are no entry requirements for U.S. citizens according to the U.S. Embassy in the Bahamas.

Barbados has discontinued all COVID-19 entry requirements the tourism board announced in September.

Barbados is also welcoming visitors to move to the island for a year for the ultimate remote work experience.

Fully vaccinated travelers by air or by cruise to Bermuda will be required to show proof of vaccination, and must upload proof prior to travel. Unvaccinated travelers must upload proof of valid travel insurance to enter, according to the government.

All travelers aged 2 and up must have Travel Authorization and will be required to pay $40 for the application.

Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba

There are no COVID-19 entry requirements for the Caribbean Netherlands according to the UK Government.

The British Virgin Islands

The British Virgin Islands have discontinued all COVID-19 entry requirements, according to the BVI government.

Cayman Islands

The Cayman Islands have removed all COVID-19 entry restrictions, according to Cayman Islands tourism board.

There are no COVID-19 entry restrictions to visit, according to the Curaçao tourism board .

Dominica has removed all pre-arrival testing along with testing on arrival for symptomatic passengers, according to the tourism board.

Dominican Republic

The Dominical Republic has removed all COVID-19 entry requirements, however, when required random testing may occur and passengers may present proof of vaccination to be exempt, according to GoDominicanRepublic.com

There are no covid entry requirements for tourists visiting Grenada, according to PureGrenada.com

The Guadeloupe Islands have dropped all COVID-19 entry requirements for visitors, t he archipelago announced in August.

All passengers 12 and older are required to present proof of vaccination or a negative PCR taken at most 72 hours before departure. Passengers aged 5-11 are required to present a negative PCR test, and passengers under 5 are exempt, according to the Department of Foreign Affairs.

For additional precautions, please see the U.S. State Department's Advisory .

Jamaica has ended all COVID-19 entry requirements, according to the U.S. Embassy.

Martinique has lifted all COVID-19 entry requirements as of August, according to the tourism board.

Since October the government of Montserrat has ended all COVID-19 requirements for entry.

Puerto Rico

All travelers will be able to enter Puerto Rico without any proof of covid vaccination or any other requirement, according to Discover Puerto Rico .

All COVID-19 entry restrictions have been lifted, according to the U.S. Embassy.

St. Kitts and Nevis

All visitors regardless of vaccination are permitted to enter St. Kitts and Nevis, according to the Tourism Authority.

Sint Maarten

Travelers to Sint Maarten are no longer required to provide travel insurance or test upon arrival if unvaccinated, the electronic health authorization requirement has also been removed.

St. Martin has removed all preexisting COVID-19 travel requirements for U.S. Citizens, according to the U.S. Embassy.

All COVID-19 restrictions have been removed, according to the St. Lucia tourism authority.

St. Vincent and the Grenadines

All COVID-19 restrictions have been lifted, according to the Ministry of Health, Wellness, and Environment.

Trinidad and Tobago

According to the U.S. Embassy there are no COVID-19 entry requirements for Trinidad and Tobago.

Turks and Caicos Islands

There are no COVID-19 entry requirements for Turks and Caicos, according to the government.

United States Virgin Islands

The U.S. Virgin Islands have removed all preexisting COVID-19 entry requirements, according to the government . The territory removed all restrictions for American travelers in May.

Related Articles

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Passports, travel and living abroad

- Travel abroad

- Foreign travel advice

Bonaire/St Eustatius/Saba

Warnings and insurance.

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office ( FCDO ) provides advice about risks of travel to help British nationals make informed decisions. Find out more about FCDO travel advice .

Before you travel

No travel can be guaranteed safe. Read all the advice in this guide and see support for British nationals abroad for information about specific travel topics.

Follow and contact FCDO travel on Twitter , Facebook and Instagram . You can also sign up to get email notifications when this advice is updated.

Travel insurance

If you choose to travel, research your destinations and get appropriate travel insurance . Insurance should cover your itinerary, planned activities and expenses in an emergency.

Related content

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

COVID-19 travel advice

A coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine can prevent you from getting COVID-19 or from becoming seriously ill due to COVID-19. But even if you're vaccinated, it's still a good idea to take precautions to protect yourself and others while traveling during the COVID-19 pandemic.

If you've had all recommended COVID-19 vaccine doses, including boosters, you're less likely to become seriously ill or spread COVID-19. You can then travel more safely within the U.S. and internationally. But international travel can still increase your risk of getting new COVID-19 variants.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that you should avoid travel until you've had all recommended COVID-19 vaccine and booster doses.

Before you travel

As you think about making travel plans, consider these questions:

- Have you been vaccinated against COVID-19? If you haven't, get vaccinated. If the vaccine requires two doses, wait two weeks after getting your second vaccine dose to travel. If the vaccine requires one dose, wait two weeks after getting the vaccine to travel. It takes time for your body to build protection after any vaccination.

- Have you had any booster doses? Having all recommended COVID-19 vaccine doses, including boosters, increases your protection from serious illness.

- Are you at increased risk for severe illness? Anyone can get COVID-19. But older adults and people of any age with certain medical conditions are at increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19.

- Do you live with someone who's at increased risk for severe illness? If you get infected while traveling, you can spread the COVID-19 virus to the people you live with when you return, even if you don't have symptoms.

- Does your home or destination have requirements or restrictions for travelers? Even if you've had all recommended vaccine doses, you must follow local, state and federal testing and travel rules.

Check local requirements, restrictions and situations

Some state, local and territorial governments have requirements, such as requiring people to wear masks, get tested, be vaccinated or stay isolated for a period of time after arrival. Before you go, check for requirements at your destination and anywhere you might stop along the way.

Keep in mind these can change often and quickly depending on local conditions. It's also important to understand that the COVID-19 situation, such as the level of spread and presence of variants, varies in each country. Check back for updates as your trip gets closer.

Travel and testing

For vaccinated people.

If you have been fully vaccinated, the CDC states that you don't need to get tested before or after your trip within the U.S. or stay home (quarantine) after you return.

If you're planning to travel internationally outside the U.S., the CDC states you don't need to get tested before your trip unless it's required at your destination. Before arriving to the U.S., you need a negative test within the last day before your arrival or a record of recovery from COVID-19 in the last three months.

After you arrive in the U.S., the CDC recommends getting tested with a viral test 3 to 5 days after your trip. If you're traveling to the U.S. and you aren't a citizen, you need to be fully vaccinated and have proof of vaccination.

You don't need to quarantine when you arrive in the U.S. But check for any symptoms. Stay at home if you develop symptoms.

For unvaccinated people

Testing before and after travel can lower the risk of spreading the virus that causes COVID-19. If you haven't been vaccinated, the CDC recommends getting a viral test within three days before your trip. Delay travel if you're waiting for test results. Keep a copy of your results with you when you travel.

Repeat the test 3 to 5 days after your trip. Stay home for five days after travel.

If at any point you test positive for the virus that causes COVID-19, stay home. Stay at home and away from others if you develop symptoms. Follow public health recommendations.

Stay safe when you travel

In the U.S., you must wear a face mask on planes, buses, trains and other forms of public transportation. The mask must fit snugly and cover both your mouth and nose.

Follow these steps to protect yourself and others when you travel:

- Get vaccinated.

- Keep distance between yourself and others (within about 6 feet, or 2 meters) when you're in indoor public spaces if you're not fully vaccinated. This is especially important if you have a higher risk of serious illness.

- Avoid contact with anyone who is sick or has symptoms.

- Avoid crowds and indoor places that have poor air flow (ventilation).

- Don't touch frequently touched surfaces, such as handrails, elevator buttons and kiosks. If you must touch these surfaces, use hand sanitizer or wash your hands afterward.

- Wear a face mask in indoor public spaces. The CDC recommends wearing the most protective mask possible that you'll wear regularly and that fits. If you are in an area with a high number of new COVID-19 cases, wear a mask in indoor public places and outdoors in crowded areas or when you're in close contact with people who aren't vaccinated.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth.

- Cover coughs and sneezes.

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds.

- If soap and water aren't available, use a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol. Cover all surfaces of your hands and rub your hands together until they feel dry.

- Don't eat or drink on public transportation. That way you can keep your mask on the whole time.

Because of the high air flow and air filter efficiency on airplanes, most viruses such as the COVID-19 virus don't spread easily on flights. Wearing masks on planes has likely helped lower the risk of getting the COVID-19 virus on flights too.

However, air travel involves spending time in security lines and airport terminals, which can bring you in close contact with other people. Getting vaccinated and wearing a mask when traveling can help protect you from COVID-19 while traveling.

The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) has increased cleaning and disinfecting of surfaces and equipment, including bins, at screening checkpoints. TSA has also made changes to the screening process:

- Travelers must wear masks during screening. However, TSA employees may ask travelers to adjust masks for identification purposes.

- Travelers should keep a distance of 6 feet apart from other travelers when possible.

- Instead of handing boarding passes to TSA officers, travelers should place passes (paper or electronic) directly on the scanner and then hold them up for inspection.

- Each traveler may have one container of hand sanitizer up to 12 ounces (about 350 milliliters) in a carry-on bag. These containers will need to be taken out for screening.

- Personal items such as keys, wallets and phones should be placed in carry-on bags instead of bins. This reduces the handling of these items during screening.

- Food items should be carried in a plastic bag and placed in a bin for screening. Separating food from carry-on bags lessens the likelihood that screeners will need to open bags for inspection.

Be sure to wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds directly before and after going through screening.

Public transportation

If you travel by bus or train and you aren't vaccinated, be aware that sitting or standing within 6 feet (2 meters) of others for a long period can put you at higher risk of getting or spreading COVID-19. Follow the precautions described above for protecting yourself during travel.

Even if you fly, you may need transportation once you arrive at your destination. You can search car rental options and their cleaning policies on the internet. If you plan to stay at a hotel, check into shuttle service availability.

If you'll be using public transportation and you aren't vaccinated, continue physical distancing and wearing a mask after reaching your destination.

Hotels and other lodging

The hotel industry knows that travelers are concerned about COVID-19 and safety. Check any major hotel's website for information about how it's protecting guests and staff. Some best practices include:

- Enhanced cleaning procedures

- Physical distancing recommendations indoors for people who aren't vaccinated

- Mask-wearing and regular hand-washing by staff

- Mask-wearing indoors for guests in public places in areas that have high cases of COVID-19

- Vaccine recommendations for staff

- Isolation and testing guidelines for staff who've been exposed to COVID-19

- Contactless payment

- Set of rules in case a guest becomes ill, such as closing the room for cleaning and disinfecting

- Indoor air quality measures, such as regular system and air filter maintenance, and suggestions to add air cleaners that can filter viruses and bacteria from the air

Vacation rentals, too, are enhancing their cleaning procedures. They're committed to following public health guidelines, such as using masks and gloves when cleaning, and building in a waiting period between guests.

Make a packing list

When it's time to pack for your trip, grab any medications you may need on your trip and these essential safe-travel supplies:

- Alcohol-based hand sanitizer (at least 60% alcohol)

- Disinfectant wipes (at least 70% alcohol)

- Thermometer

Considerations for people at increased risk

Anyone can get very ill from the virus that causes COVID-19. But older adults and people of any age with certain medical conditions are at increased risk for severe illness. This may include people with cancer, serious heart problems and a weakened immune system. Getting the recommended COVID-19 vaccine and booster doses can help lower your risk of being severely ill from COVID-19.

Travel increases your chance of getting and spreading COVID-19. If you're unvaccinated, staying home is the best way to protect yourself and others from COVID-19. If you must travel and aren't vaccinated, talk with your health care provider and ask about any additional precautions you may need to take.

Remember safety first

Even the most detailed and organized plans may need to be set aside when someone gets ill. Stay home if you or any of your travel companions:

- Have signs or symptoms, are sick or think you have COVID-19

- Are waiting for results of a COVID-19 test

- Have been diagnosed with COVID-19

- Have had close contact with someone with COVID-19 in the past five days and you're not up to date with your COVID-19 vaccines

If you've had close contact with someone with COVID-19, get tested after at least five days. Wait to travel until you have a negative test. Wear a mask if you travel up to 10 days after you've had close contact with someone with COVID-19.

©2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MRMER). All rights reserved.

Advertisement

Supported by

If You Test Positive for Covid, Can You Still Travel?

With coronavirus cases on the rise, summer travelers are once again facing difficult questions. Here’s the latest travel guidance from health experts.

- Share full article

By Shannon Sims

As new coronavirus variants gain traction across the United States, summer travelers are facing a familiar and tiresome question: How will the ever-mutating virus affect travel plans?

In light of updated guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , the answers may be slightly different from those in previous years.

Here’s what to know about traveling this summer if you’re worried about — or think you might have — Covid-19.

What’s going on with Covid?

Recent C.D.C. data show that Covid infections are rising or most likely rising in more than 40 states. Hospitalization rates and deaths, while low compared with the peaks seen in previous years, are also on the rise.

The uptick is tied to a handful of variants — named KP.2, KP.3 and LB.1 — that now account for a majority of new cases .

At the same time, record numbers of people are traveling by car and plane.

I’d planned to travel, but I’m sick with Covid. What should I do?

In short: You should probably delay or cancel your trip.

If you tested positive or are experiencing Covid symptoms, which include fever, chills, fatigue, a cough, a runny nose, body aches and a headache, the C.D.C. recommends that you stay home and keep away from others.

According to its latest guidelines, the agency advises waiting until at least 24 hours after you are fever-free and your overall symptoms are improving before going back to normal activities, including travel.

What are the isolation rules?

New C.D.C. guidelines issued in March made significant changes to the recommended isolation period for people with Covid.

The agency now says that you can resume daily activities if you meet two requirements : You have been fever-free for at least 24 hours (without the use of fever-reducing medications) and your symptoms are improving overall. Previously, the agency recommended isolating for at least five days, plus a period of post-isolation precautions.

Even after your isolation period, you may still be able to spread the virus to others, which is why the C.D.C. encourages you to continue to take precautions for the next five days: Use masks, wash your hands frequently, practice physical distancing, clean your air by opening windows or purifying it, and continue testing yourself before gathering around others.

Are there any lingering testing or vaccine requirements?

Travelers no longer need to show proof of being vaccinated against Covid or take a Covid test to enter the U.S. (This applies to both U.S. citizens and noncitizens.)

The same is true in Europe and most other countries.

How can I prepare before traveling?

First, make sure you stay up-to-date with Covid vaccines .

Next, plan to bring any items that would be helpful should you become sick while traveling.

“Make sure to take a good first aid or medication kit with you,” said Vicki Sowards, the director of nursing resources for Passport Health , which provides travel medical services. Ms. Sowards recommended that your kit include medications that you usually take when you are ill, as well as Covid tests.

You may want to consider packing medications that can help alleviate the symptoms of Covid, like painkillers, cold and flu medicines, and fever reducers. Bringing along some electrolyte tablets (or powdered Gatorade) can also help if you get sick.

Ms. Sowards also suggested speaking with your physician before traveling, particularly if you’re in a vulnerable or high-risk group. Some doctors might prescribe the antiviral Paxlovid as a precautionary measure, she said, to be taken in the event of a Covid infection.

How can I stay safe while traveling?

Wearing a mask on a plane or in crowded areas is still a good idea, said Ms. Sowards. Covid is spread through airborne particles and droplets, “so protecting yourself is paramount, especially if you are immunocompromised or have chronic health conditions.”

If you do get sick, start wearing a mask and using over-the-counter medications such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen for fever or joint aches, Ms. Sowards advised.

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram and sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to get expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places to Go in 2024 .

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

CDC Recommends Updated 2024-2025 COVID-19 and Flu Vaccines for Fall/Winter Virus Season

For Immediate Release: June 27, 2024 Contact: Media Relations (404) 639-3286

Today, CDC recommended the updated 2024-2025 COVID-19 vaccines and the updated 2024-2025 flu vaccines to protect against severe COVID-19 and flu this fall and winter.

It is safe to receive COVID-19 and flu vaccines at the same visit. Data continue to show the importance of vaccination to protect against severe outcomes of COVID-19 and flu, including hospitalization and death. In 2023, more than 916,300 people were hospitalized due to COVID-19 and more than 75,500 people died from COVID-19. During the 2023-2024 flu season, more than 44,900 people are estimated to have died from flu complications.

Updated 2024-2025 COVID-19 Vaccine Recommendation

CDC recommends everyone ages 6 months and older receive an updated 2024-2025 COVID-19 vaccine to protect against the potentially serious outcomes of COVID-19 this fall and winter whether or not they have ever previously been vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine. Updated COVID-19 vaccines will be available from Moderna, Novavax, and Pfizer later this year. This recommendation will take effect as soon as the new vaccines are available.

The virus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, is always changing and protection from COVID-19 vaccines declines over time. Receiving an updated 2024-2025 COVID-19 vaccine can restore and enhance protection against the virus variants currently responsible for most infections and hospitalizations in the United States. COVID-19 vaccination also reduces the chance of suffering the effects of Long COVID, which can develop during or following acute infection and last for an extended duration.

Last season, people who received a 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine saw greater protection against illness and hospitalization than those who did not receive a 2023-2024 vaccine. To date, hundreds of millions of people have safely received a COVID-19 vaccine under the most intense vaccine safety monitoring in United States history.

Updated 2024-2025 Flu Vaccine Recommendation

CDC recommends everyone 6 months of age and older, with rare exceptions, receive an updated 2024-2025 flu vaccine to reduce the risk of influenza and its potentially serious complications this fall and winter. CDC encourages providers to begin their influenza vaccination planning efforts now and to vaccinate patients as indicated once 2024-2025 influenza vaccines become available .

Most people need only one dose of the flu vaccine each season. While CDC recommends flu vaccination as long as influenza viruses are circulating, September and October remain the best times for most people to get vaccinated. Flu vaccination in July and August is not recommended for most people, but there are several considerations regarding vaccination during those months for specific groups:

- Pregnant people who are in their third trimester can get a flu vaccine in July or August to protect their babies from flu after birth, when they are too young to get vaccinated.

- Children who need two doses of the flu vaccine should get their first dose of vaccine as soon as it becomes available. The second dose should be given at least four weeks after the first.

- Vaccination in July or August can be considered for children who have health care visits during those months if there might not be another opportunity to vaccinate them.

- For adults (especially those 65 years old and older) and pregnant people in the first and second trimester, vaccination in July and August should be avoided unless it won’t be possible to vaccinate in September or October.

Updated 2024-2025 flu vaccines will all be trivalent and will protect against an H1N1, H3N2 and a B/Victoria lineage virus. The composition of this season’s vaccine compared to last has been updated with a new influenza A(H3N2) virus .

For more information on updated COVID-19 vaccines visit: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) | CDC . For more information on updated flu vaccines visit: Seasonal Flu Vaccines | CDC .

The following statement is attributable to CDC Director Dr. Mandy Cohen:

“Our top recommendation for protecting yourself and your loved ones from respiratory illness is to get vaccinated,” said Mandy Cohen, M.D., M.P.H. “Make a plan now for you and your family to get both updated flu and COVID vaccines this fall, ahead of the respiratory virus season.”

### U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Whether diseases start at home or abroad, are curable or preventable, chronic or acute, or from human activity or deliberate attack, CDC’s world-leading experts protect lives and livelihoods, national security and the U.S. economy by providing timely, commonsense information, and rapidly identifying and responding to diseases, including outbreaks and illnesses. CDC drives science, public health research, and data innovation in communities across the country by investing in local initiatives to protect everyone’s health.

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

- Data & Statistics

- Freedom of Information Act Office

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Public support for air travel restrictions to address COVID-19 or climate change

Affiliation.

- 1 CICERO Center for International Climate Research, P.O. Box 1129 Blindern, 0318 Oslo, Norway.

- PMID: 36568359

- PMCID: PMC9760087

- DOI: 10.1016/j.trd.2021.102767

An improved understanding of public support is essential to design effective and feasible climate policies for aviation. Our motivation is the contrast between high support for air travel restrictions responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and low support for restrictions to combat climate change. Can the same factors explain individuals' support for restrictive measures across two different problems? Using a survey, we find that largely the same factors explain support. Support increases with expected effectiveness, perceived threat and imminence of the problem, shorter expected duration of the measure, knowledge, and trust, while support decreases with expected negative consequences for self and the poor. When controlling for all perceptions, there is no significant residual difference in support depending on whether the measures address climate change or COVID-19. The level of support differs because COVID-19 is perceived as a more imminent threat, and because measures are expected to be shorter-lasting and more effective.

Keywords: Air travel; COVID-19; Climate change; Public support; Restrictive measures.

© 2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to "About this site"

Language selection

Search travel.gc.ca.

Help us to improve our website. Take our survey !

COVID-19: travel health notice for all travellers

Bonaire travel advice

Latest updates: The Health section was updated - travel health information (Public Health Agency of Canada)

Last updated: July 2, 2024 09:25 ET

On this page

Safety and security, entry and exit requirements, laws and culture, natural disasters and climate, bonaire - take normal security precautions.

Take normal security precautions in Bonaire.

Back to top

Petty crime, such as pickpocketing and purse snatching, occurs in Bonaire.

Residential break-ins and theft from vehicles, hotel rooms and rental units also take place.

- Ensure that your belongings, including your passport and other travel documents, are secure at all times

- Never leave valuables such as jewellery, cell phones, electronics, wallets or bags unattended on the beach or in your vehicle

- Avoid unpopulated areas and unpatrolled beaches after dark

- Check with local authorities to determine which beaches are safe

Women's safety

Women travelling alone may be subject to some forms of harassment and verbal abuse.

Advice for women travellers

Water activities

Coastal waters can be dangerous. Rescue services may not be consistent with Canadian standards.

Follow the instructions and warnings of local authorities.

If you are planning to take part in water sports such as scuba diving, jet skiing or parasailing:

- ensure that equipment is safe and in good condition

- ensure helmets and life jackets are available

- avoid participating in any water activities when you are under the influence of alcohol or other substances

- check that your travel insurance covers accidents related to recreational activities

Water safety abroad

Wildlife viewing

Wild animals can be dangerous, particularly if you are on foot or at close range.

- Always maintain a safe distance when observing wildlife

- Only exit a vehicle when a professional guide or warden says it’s safe to do so

- Only use reputable and professional guides or tour operators

- Closely follow park regulations and wardens’ advice

Road safety

Major roads are in good condition, but many drivers don’t respect traffic laws.

Animals on the road pose a hazard.

Road signs are different from Canada. Familiarize yourself with the signs before driving.

Public transportation

Public transportation in Bonaire is fairly limited. There is no public bus system operating. Taxis are the only form of public transportation on the island.

Taxis in Bonaire must be registered and have license plates marked with “TX”.

Taxis are not metered and operate on a flat rate by destination set by the government. Despite the regulated price, agree on a fare prior to departure.

We do not make assessments on the compliance of foreign domestic airlines with international safety standards.

Information about foreign domestic airlines

Every country or territory decides who can enter or exit through its borders. The Government of Canada cannot intervene on your behalf if you do not meet your destination’s entry or exit requirements.

We have obtained the information on this page from Dutch authorities. It can, however, change at any time.

Verify this information with the Foreign Representatives in Canada .

Entry requirements vary depending on the type of passport you use for travel.

Before you travel, check with your transportation company about passport requirements. Its rules on passport validity may be more stringent than the country’s entry rules.

Regular Canadian passport

Your passport must be valid for the duration of your stay in Bonaire.

Passport for official travel

Different entry rules may apply.

Official travel

Passport with “X” gender identifier

While the Government of Canada issues passports with an “X” gender identifier, it cannot guarantee your entry or transit through other countries. You might face entry restrictions in countries that do not recognize the “X” gender identifier. Before you leave, check with the closest foreign representative for your destination.

Other travel documents

Different entry rules may apply when travelling with a temporary passport or an emergency travel document. Before you leave, check with the closest foreign representative for your destination.

Useful links

- Foreign Representatives in Canada

- Canadian passports

Tourist visa: not required for stays of up to 90 days in a 180-day period Business visa: not required for stays of up to 90 days in a 180-day period Work permit: required Student visa: required

Visitor entry tax

You must pay a $75 USD visitor entry tax to visit Bonaire. The tax can be paid online using the official government site.

Visitor entry tax – Government of Bonaire

Other entry requirements

Customs officials may ask you to show them:

- a return or onward ticket

- proof of the purpose of your stay

- proof of sufficient funds to cover your stay

- proof of valid health insurance

- proof of accommodation for your stay

Other entry requirements may apply.

- Bonaire Immigration and Entry Requirements – Info Bonaire

- Requirements for travelling without a visa – Government of the Netherlands

- Children and travel

Learn more about travelling with children .

Yellow fever

Learn about potential entry requirements related to yellow fever (vaccines section).

Relevant Travel Health Notices

- Global Measles Notice - 13 March, 2024

- COVID-19 and International Travel - 13 March, 2024

- Zika virus: Advice for travellers - 31 August, 2023

- Dengue: Advice for travellers - 2 July, 2024

This section contains information on possible health risks and restrictions regularly found or ongoing in the destination. Follow this advice to lower your risk of becoming ill while travelling. Not all risks are listed below.

Consult a health care professional or visit a travel health clinic preferably 6 weeks before you travel to get personalized health advice and recommendations.

Routine vaccines

Be sure that your routine vaccinations , as per your province or territory , are up-to-date before travelling, regardless of your destination.

Some of these vaccinations include measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, varicella (chickenpox), influenza and others.

Pre-travel vaccines and medications

You may be at risk for preventable diseases while travelling in this destination. Talk to a travel health professional about which medications or vaccines may be right for you, based on your destination and itinerary.

Yellow fever is a disease caused by a flavivirus from the bite of an infected mosquito.

Travellers get vaccinated either because it is required to enter a country or because it is recommended for their protection.

- There is no risk of yellow fever in this country.

Country Entry Requirement*

- Proof of vaccination is required if you are coming from or have transited through an airport of a country where yellow fever occurs.

Recommendation

- Vaccination is not recommended.

- Discuss travel plans, activities, and destinations with a health care professional.

- Contact a designated Yellow Fever Vaccination Centre well in advance of your trip to arrange for vaccination.

About Yellow Fever

Yellow Fever Vaccination Centres in Canada * It is important to note that country entry requirements may not reflect your risk of yellow fever at your destination. It is recommended that you contact the nearest diplomatic or consular office of the destination(s) you will be visiting to verify any additional entry requirements.

There is a risk of hepatitis A in this destination. It is a disease of the liver. People can get hepatitis A if they ingest contaminated food or water, eat foods prepared by an infectious person, or if they have close physical contact (such as oral-anal sex) with an infectious person, although casual contact among people does not spread the virus.

Practise safe food and water precautions and wash your hands often. Vaccination is recommended for all travellers to areas where hepatitis A is present.

Hepatitis B is a risk in every destination. It is a viral liver disease that is easily transmitted from one person to another through exposure to blood and body fluids containing the hepatitis B virus. Travellers who may be exposed to blood or other bodily fluids (e.g., through sexual contact, medical treatment, sharing needles, tattooing, acupuncture or occupational exposure) are at higher risk of getting hepatitis B.

Hepatitis B vaccination is recommended for all travellers. Prevent hepatitis B infection by practicing safe sex, only using new and sterile drug equipment, and only getting tattoos and piercings in settings that follow public health regulations and standards.

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease. It can spread quickly from person to person by direct contact and through droplets in the air.

Anyone who is not protected against measles is at risk of being infected with it when travelling internationally.

Regardless of where you are going, talk to a health care professional before travelling to make sure you are fully protected against measles.

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious viral disease. It can spread from person to person by direct contact and through droplets in the air.

It is recommended that all eligible travellers complete a COVID-19 vaccine series along with any additional recommended doses in Canada before travelling. Evidence shows that vaccines are very effective at preventing severe illness, hospitalization and death from COVID-19. While vaccination provides better protection against serious illness, you may still be at risk of infection from the virus that causes COVID-19. Anyone who has not completed a vaccine series is at increased risk of being infected with the virus that causes COVID-19 and is at greater risk for severe disease when travelling internationally.

Before travelling, verify your destination’s COVID-19 vaccination entry/exit requirements. Regardless of where you are going, talk to a health care professional before travelling to make sure you are adequately protected against COVID-19.

The best way to protect yourself from seasonal influenza (flu) is to get vaccinated every year. Get the flu shot at least 2 weeks before travelling.

The flu occurs worldwide.

- In the Northern Hemisphere, the flu season usually runs from November to April.

- In the Southern Hemisphere, the flu season usually runs between April and October.

- In the tropics, there is flu activity year round.

The flu vaccine available in one hemisphere may only offer partial protection against the flu in the other hemisphere.

The flu virus spreads from person to person when they cough or sneeze or by touching objects and surfaces that have been contaminated with the virus. Clean your hands often and wear a mask if you have a fever or respiratory symptoms.